How Nonprofit Hospitals Can Profit – Handsomely

The Charlotte Observer and the News & Observer in Raleigh, both owned by the McClatchy newspaper chain, collaborated in 2011 and 2012 on an extraordinary series about North Carolina nonprofit hospitals. In Charlotte, investigative reporter Ames Alexander and medical writer Karen Garloch worked with Jim Walser, senior editor/investigations. In Raleigh, Steve Riley, senior editor for investigations, worked with investigative reporter Joseph Neff and news research database editor David Raynor. The reporters collectively composed the following account of how they reported the story.

In 2009, as the debate about health care reform picked up steam in Washington, D.C., an editor at The News & Observer in Raleigh, N.C., posed a question: Should the newspaper take a deep look at the cost of health care?

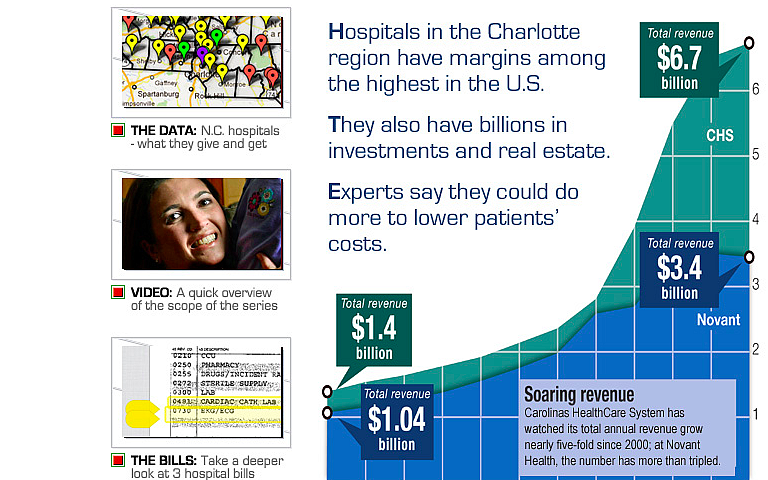

A series of interviews and some database work led to two key decisions: Concentrate on hospitals. And ask colleagues at The Charlotte Observer to join the research. North Carolina's largest hospital system, Carolinas HealthCare, was based in Charlotte. And it was suing thousands of its patients each year for payment. If the two papers worked together, they could run a statewide series, with more reach and impact.

The early stages

Early in our reporting, we read many academic studies, talked with many hospital experts around the country and developed a few fundamental questions:

– How profitable were North Carolina’s nonprofit hospitals?

– Were they giving back to the community as much as they were getting in the form of tax breaks?

– And how were hospitals treating those who couldn’t afford to pay their bills?

How we measured hospital profits

To answer the profit question, we made great use of the American Hospital Directory – ahd.com. AHD draws financial data from Medicare cost reports, which hospitals must file each year with the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. It also makes its data available for free to reporters, and can even do custom data runs. So that can be a tremendous – and affordable – research tool.

(You can get more detailed Medicare cost report by going to another site called costreportedata.com. That site also provides free subscriptions to the media.)

By examining audited financial statements, we determined the profit margins of larger hospital systems.

How we gauged hospital charitability

To examine how charitable the state’s hospitals were, we relied on a different set of data: the “community benefit reports” filed with the state hospital association.

Those figures, coupled with the data we got from AHD, allowed us to determine the percentage of expenses that each hospital devoted to charity care. The range was wide – from less than 1 percent at some hospitals to more than 10 percent at others. But most hospitals were spending less than 3 percent of their budgets on charity care.

In most communities, those charity care percentages were dwarfed by the percentages of people without jobs and health insurance. Such data, along with a lot of shoe-leather reporting, made it clear that hospital charity care in many communities wasn’t sufficient to meet the need.

Measuring the value of hospital tax exemptions isn’t easy. No group or agency keeps those figures, and there’s not enough publicly available data to calculate the numbers precisely. But we came up with estimates by examining the taxes paid by three large for-profit hospital chains. And for most N.C. hospitals, the estimated tax breaks exceeded what was spent on charity care.

Most hospitals have charity-care policies, but many do little to publicize them. Many uninsured patients in the Charlotte and Raleigh areas told us they were never informed about charity care. And more than a third of the state’s 100-plus general hospitals didn’t post key details about their charity care policies on their web sites, we found.

How we examined the way hospitals treated patients who don’t pay

To understand how hospitals were treating patients who didn’t pay their bills, we got data from the N.C. Administrative Office of the Courts on bill collections lawsuits filed by hospitals. We then visited courthouses and hand-checked hundreds of those suits. Our data and field checks showed us that N.C. hospitals had filed more than 40,000 bill-collections suits over a five-year-period. We also found that just two entities – a hospital chain called Carolinas HealthCare and Wilkes Regional Medical Center, one of the individual hospitals it manages – had filed most of those suits.

We took an in-depth look at many of those cases and discovered that most of those patients were uninsured, and that some of them probably should have qualified for charity care.

Most N.C. hospitals, we found, rarely sue patients. But virtually all use commission-driven collections agencies, which can ruin a patient’s credit. In complaints to state agencies, dozens of former patients contend collections agencies harassed them, sometimes reporting inaccurate information to credit bureaus or continuing to pursue them long after they paid their bills.

Finding people

Patients and their stories were crucial to the series, helping us put a human face on what threatened to be data-heavy stories.

The lawsuits filed against patients pointed us to many who had tragic stories to tell.

We also obtained consumer complaints filed with the Consumer Affairs Division of the state Attorney General’s office, and with the state Department of Insurance. We requested all complaints against hospitals and collection agencies.

We asked patient advocates to send cases our way. We canvassed lines at food pantries to ask people if they had problems with hospital bills. We also did put out a fetcher on the Observer’s Public Insight Network, a database of readers who have agreed to share their knowledge for Observer stories.

Many patients were kind enough to share their hospital bills with us. We used Document Cloud to annotate several of those bills, and to illustrate the large markups on some drugs and procedures.

We built a spreadsheet to capture key data about each patient: Were they insured? Were they informed about charity care? Were they sued? Did they appear to qualify for charity care?

How we got the industry’s take

We took pains to make sure we accurately and thoroughly reported the hospital industry’s perspective on what we were hearing and seeing. We began talking with hospital officials early in the process, and ultimately got in-depth interviews with many hospital CEOs and CFOs. We also asked the state hospital association to weigh in on each of seven proposals that patient advocates said could help address the problems we identified.

Tips for journalists pursuing similar work

– Ask insurers to share their wisdom and data. In our case, two insurance companies agreed to provide and analyze data that they don’t ordinarily make public.

– To find patients, pull lawsuits and complaint files kept by state agencies. Talk with lawyers who represent the indigent. And consult with people who head patient support groups.

– Bond disclosure documents can also yield key information about hospitals, including audited financial reports. You can obtain those through emma.msrb.org, a handy site maintained by the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board.

– Be persistent. You’ll likely find, as we did, that many patients won’t want to discuss their bills or experiences on the record, for fear of antagonizing the hospitals or doctors they rely on for care. But if you talk with enough people, you’ll likely find some who will be willing to talk publicly.

Postscript: A series with impact

Since our stories ran, scores of readers, experts and public officials have applauded the stories and have increased the pressure for change. Here are a few of the developments:

– U.S. Sen. Charles Grassley of Iowa demanded that three of North Carolina’s largest hospitals share information about their use of a rapidly growing 340B discount drug program highlighted by the Observer, saying they don’t appear to be passing along the “massive” savings to patients.

– In March 2013, two state senators, including Bob Rucho, a Republican from the Charlotte area, introduced legislation to require hospitals to publicly disclose prices on the 50 most common medical procedures. The bill would also give financial rewards for hospitals that are able to provide low-cost care, ban a type of double billing now common in radiology, and prohibit state-owned hospitals from seizing the tax refunds of patients who don't pay their bills.

– In response to the series, state legislators have also introduced legislation to make it easier for physicians to open same-day surgery centers that would typically charge far less than hospitals for outpatient procedures. The legislation faces stiff opposition from the North Carolina Hospital Association, which represents the state's powerful hospital industry.

– The state NAACP and other anti-poverty groups called for Carolinas HealthCare System in Charlotte to stop suing patients and putting liens on their homes.