The Legacy of Pollution in One of Denver's Oldest Neighborhoods

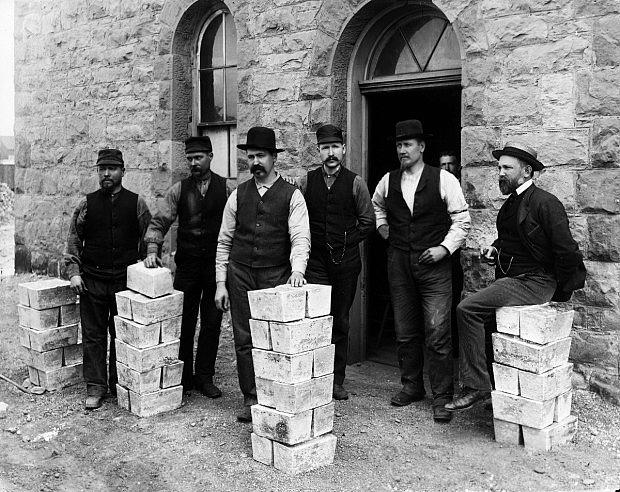

My initial idea was to focus on the old Asarco smelter just north of downtown Denver. The old refinery, with its landmark towering brick smokestack, used to be the largest smelter in North America. This is where the gold and silver from Colorado’s celebrated mountain mines was processed for more than 100 years, until the multinational Asarco closed it down in 2006 after declaring bankruptcy.

What was left behind was a 75-acre proposed Superfund site, contaminated with lead and cadmium and other heavy metals. A plume of contaminated water seeps nearly a mile before dumping out into the South Platte River, a major water supply. Three lawsuits – two class action suits filed by residents living in the surrounding neighborhood of Globeville and another by the State of Colorado – forced Asarco to clean up the mess.

The status of the cleanup, and the impacts of the site on the working class residents living nearby, has for years been grossly undercovered as a news story. I quickly determined that the story was not just about the Asarco smelter and its potential health impacts. A critical component was also the health of the surrounding neighborhood in general.

Though Globeville is one of the oldest neighborhoods in Denver, with a rich history, it’s also one of the last areas of the city without a specific development plan. The area has long been neglected by elected officials who are supposed to represent the neighborhood’s interests. The main thoroughfare in and out of Globeville is a rutted, two-lane mess. Many of the residential alleys are still unpaved. Sidewalks are missing. The residents have asked for bus benches and trashcans for their alleys, without success. In addition, the community is in the gritty cradle of the junction of two major interstate highways, which further contributes adverse impacts.

I decided to focus on the three major areas – Globeville’s history; the status of the lawsuits and cleanup of the Asarco smelter site; and the politics that have stalled any ability to make this a vibrant area of the city.

The history and the lawsuit elements of the story were fairly easy to cover. I spent several days pouring through the archives in the Colorado History Museum, going through microfiches and finding great anecdotes and stories about Globeville and the smelter. I was lucky enough to connect early on with the project manager for the state health department. He has been overseeing the cleanup of the contaminated smelter site and surrounding neighborhood for 20 years. I filed open records requests to review documents about the lawsuits and the cleanup. The list describing the related documents in existence was itself several hundred pages long. In the end, I relied heavily on the judges’ consent decrees, and interviews with lead plaintiffs and the attorney who had represented the neighbors.

As I spent time in Globeville, something else struck me. My sources weren’t exactly talking to me about it, but it often smelled. As in, the neighborhood smelled bad, like chemicals or tar. One day, after I had spent several hours in Globeville with a photographer, I had to go home and lay down, with a splitting headache. My photographer reported also not feeling well.

I asked the couple that had been the lead plaintiffs about the odor, and they looked at each other, and then me. Yes, they were aware of the stench. In fact, they have been trying to seek remedy for years. Six years. Their complaints had been brushed aside by their city councilwoman, by the state health department, by anyone with any authority to do anything. So, with the help of a nonprofit group working in the neighborhood, they had gotten a grant to literally take matters into their own hands. They were testing the air themselves to try to determine the source of the industrial smell, and whether it contained noxious chemicals.

No one had initially wanted to say anything about the latest potential health risk. They were afraid to further stigmatize their neighborhood. The lawsuits, still fresh in Globeville’s collective memory, had pitted neighbor against neighbor. They didn’t want to risk tearing the scab off old wounds.

I quickly realized that this development was a critical element in the story. The fact that state health officials and elected representatives could be so nonchalant about this health risk was not lost on me – nor was it lost on health and environmental justice advocates. The neighbors began to open up.

The resulting series was broken into three parts. Part 1 detailed the rich history of Globeville. I told the story in part through the life of the president of the neighborhood association, whose grandfather immigrated to Globeville to work the famous smelter. The smelter had made the Guggenheims and Rockefellers into billionaires, but the residents had been left with a contaminated proposed Superfund site, among other problems.

Part 2 detailed the lawsuits that forced Asarco to clean up the contaminated smelter and the neighborhood. As a result of the lawsuits, the mining company had to replace 12-18 inches of topsoil at hundreds of surrounding residences. In addition, the company has to clean up the 75 acres of the former smelter and halt the plume of contaminated water seeping into the South Platte River. So I provided an update on the work being done, including the fact that they plan to stabilize the heavy metals with a mixture of molasses and alcohol. Yes, molasses and alcohol.

Part 3 focused entirely to the latest battle by neighbors -- trying to get state and city officials to do something about the terrible and potentially unhealthy odor that routinely stink bombs the neighborhood.

The week the story appeared on www.ColoradoPublicNews.com, the mayor of Denver announced that the city is activating a process to create a master plan for what health and environmental justice advocates have come to refer to as Denver’s “Last Frontier.” Over the course of the next several months, city leaders began vowing to work directly with Globeville residents to tackle many of the problems plaguing the neighborhood.

While that immediate impact was great news, we were also faced with the challenge of getting the Globeville series out to a broad audience. Many of our media partners are in other parts of Colorado and weren’t that interested in running a Denver-specific, long-form narrative series. However, several were happy to link to the series on their websites. And, several of our radio station partners, including KGNU and KUVO invited me on the air to be interviewed about the series.

The Globeville community is now nearly 70 percent Hispanic. Viva Colorado, the Spanish-language publication of the Denver Post, was thrilled to run a shortened version of the series. I merely took the package, shortened it to 1,200 words, and they provided the translation for their print edition, which is distributed to every home in Globeville. I’ve also been reaching out to health, environmental, history and city planning bloggers asking them to link to the series (and am still working through my list!).

And finally, our member station Colorado Public Television Channel 12 has expressed interest in producing a half-hour show about the series and about Globeville.

We are working on other ideas to keep the story out there, and make sure to provide follow-ups. For those of you doing these types of projects, I would recommend the following (provided as bullet points, to keep it short and sweet):

- File open records requests early and often

- Find good characters to help tell your story with authority, honesty and genuineness

- When hashing over history, make it come alive with real stories about real people

- Figure out early how to promote the story. Be creative, like calling in radio, TV and bloggers

- Spend time writing, rewriting and rewriting again

- Follow your nose. Literally.

Photo Credit: Western History/Genealogy Dept., Denver Public Library