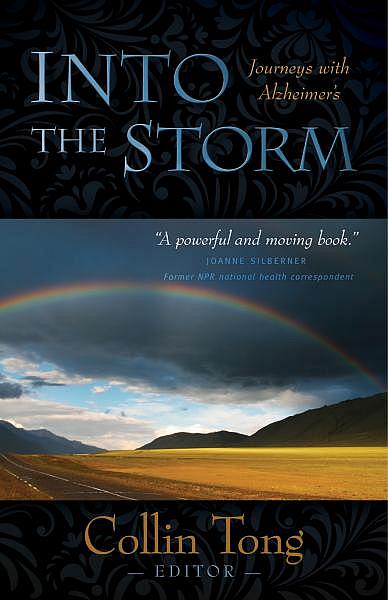

New Book Chronicles Journeys with Alzheimer’s Disease

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is an edited excerpt from Collin Tong’s new book “Into the Storm: Journey’s with Alzheimer’s,” which will be available by the Book Publishers Network in January 2014. In Tong's anthology, twenty-three writers, journalists, educators, health practitioners, social workers and other caregivers across the United States share their intimate stories of caring for loved ones with Alzheimer's disease and dementia. Tong is a correspondent for Crosscut News and University Outlook magazine. He is also a Seattle-based stringer for The New York Times. He was a former Michele Clark Fellow at the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education.

It was more than fifteen years ago, in 1999, when I first discovered that my wife was having serious problems with short-term memory. We were on a walking tour of Provence in southern France when I noticed that Linda had forgotten to bring several items for our vacation.

I didn’t think anything was amiss until we returned to Seattle that October. Unanticipated events had dealt us a major blow when her younger sister, who had recently had a kidney transplant, died from complications during a routine dialysis. Linda’s memory lapses only increased during her protracted grieving process.

Coworkers noticed that Linda was having more difficulty at Seattle City Light where she had worked for twenty years as an energy conservation analyst. A normally well-organized person, she forgot her appointments and drove colleagues to distraction by endlessly repeating questions.

Linda took an extended leave-of-absence so that I could take her to see a neurologist, clinical psychologist, and other dementia specialists. All had reached the same conclusion, namely that her short-term memory loss stemmed from clinical depression, a diagnosis that later proved to be incorrect.

I continued my communications job at Washington State University and put Linda’s memory problems in the back of my mind. I didn’t realize it at the time but I was in denial and slow to face the dreaded possibility that she might be suffering from something more consequential than depression. Indeed I was only living through the stages of grieving itself: denial, despair, frustration, and increasing isolation from family, friends, and even the person I was caring for.

My normal way of dealing with terminal illness was to not deal with it. Like many people who care for a loved one with dementia, I knew little about Alzheimer’s and was hesitant to learn more. I went to bookstores to scan medical books about the disease, but the more I read the less hopeful I became for any improvement in Linda’s condition.

As time went on, Linda’s behavior grew more erratic. Our lives became more challenging as her grief over the passing of her sister continued unabated. Overburdened by the demands of work and caregiving, I took early retirement from my university job.

My growing acceptance of Linda’s memory problems notwithstanding, I could not ignore the signs of her cognitive decline. By then, our familiar world was slowly dissolving. She was fifty-seven years old in 2005 when she was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. The news devastated our families and friends. Our lives were about to change profoundly.

The physical and emotional toll of being a full-time caregiver is daunting. However much one tries to prepare for being a caregiver, nothing adequately prepares one for the challenges of caring for a loved one. I felt overwhelmed with the daily chores of cooking, cleaning, shopping, paying bills, mowing the lawn, doing the laundry, or just attending to the daily necessities of keeping our lives afloat.

We went to church less frequently and began skipping social activities, and even did the unthinkable, missed my nephew’s wedding in California. Our friends felt our absence all the more keenly because we had been so active in the community before her debilitating illness.

Fortunately, our families in the San Francisco Bay Area and southern California helped us tackle the financial, legal, and related issues such as helping Linda to secure her Social Security disability and retirement pension. Friends brought over hot meals and cared for Linda whenever I ran errands, visited friends, or needed a break. Others helped with work around the house. Through trial and error, I learned that while being a caregiver is challenging, help is always available if one is intentional about seeking it.

Because of the unrelenting demands of 24/7 caregiving, taking good care of one’s physical and emotional well being is all too often given short shrift. Stress and anxiety inevitably lead to social isolation and the downward spiral of frustration, despair and hopelessness. Going out to lunch with friends, seeing a Mariners game, or just taking walks were replenishing.

Equally important is developing a strong network of supportive friends. Fortunately, the Alzheimer’s Association became our lifeline, along with our church in Seattle. The Alzheimer’s Association put together a comprehensive care plan for Linda.

Most important of all for me was accepting the inevitable feelings of grief and loss as Linda changed, and acknowledging the things that were beyond my control while making decisions about things I could control. At the encouragement of a social worker friend, I joined an early-onset Alzheimer’s support group in Seattle.

Sadly, ours is not a unique experience. More and more people under 65, baby boomers, are getting young-onset Alzheimer’s disease. The majority of those individuals live at home, tend to be unpaid caregivers, mostly family and friends.

Fortunately, many organizations exist that provide respite care. I helped enroll Linda at an adult day health program in Seattle, where skilled and dedicated care professionals engaged her in daily social interaction that helped maintain her health.

In the final three months of her life, Linda’s condition took a precipitous turn for the worse. Following several weeks under the care of hospice workers, she died peacefully after a brave twelve-year struggle on April 5, 2011 surrounded by family and friends in her adult family home just an hour shy of her sixty-fourth birthday.

Navigating the challenges of caring for a loved one with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease need not be a solitary journey. Indeed, as I learned, it is impossible to surmount those hurdles without reaching out to others. Because of our extended network of family and friends who went the extra mile to be our lifelines and safety net, ours has been a life-transforming and life-affirming journey.

Image by mrpbps via Flickr