A new Boston nanny hits the news

Justina Pelletier, back with her family

Nearly twenty years after the trial of British au pair Louise Woodward brought shaken baby syndrome into the headlines, the case of Irish nanny Aisling Brady McCarthy has raised the subject again in Boston newspapers, where reporters are still fresh from a different controversial diagnosis by the same child protection team.

Last week McCarthy’s attorneys filed a motion arguing not only that the science around shaken baby syndrome is falling apart but also that the physician who diagnosed the abuse has been wrong before about infant shaking. Then journalists made the connection with the high-profile case of teenager Justina Pelletier, who returned home to her parents in June after a long, bitter, and public struggle with Boston Children’s Hospital.

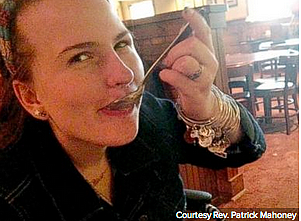

[Photo: Aisling Brady McCarthy, accused of shaking an infant, photo from the Middlesex District Attorney’s Office]

McCarthy, who is in the U.S. illegally, has been in jail since she was arrested in January of 2013, a week after reporting that 1-year-old Rehma Sabir had simply fallen unconscious in her care. The girl died in the hospital two days later.

Although doctors found no bruising, grip marks, or other external signs of assault, Rehma was diagnosed as the victim of a violent shaking, based on brain swelling and bleeding inside her head and behind her eyes, the same symptoms found in Matthew Eappen, the infant quit breathing while in the care of Louise Woodward in 1997.

Last week’s Boston Globe coverage offered this perspective on the abuse diagnosis, from a physician not involved in the case:

“Bleeding in the back of the eye rarely happens absent abuse,” said Robert Sege, medical director of the Child Protection Team at Boston Medical Center.

Sege said abusive head trauma is a leading cause of death of infants, and its existence is a “settled scientific fact,” according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

During a grand jury hearing in 2013, prosecutors argued that McCarthy had inflicted both the brain injury and a number of “compression fractures” found in Rehma’s spine, but a bone specialist for the state later concluded that the fractures were 3 to 4 weeks old, meaning they happened while the girl was out of the country with her family, not in McCarthy’s care. When the bone evidence emerged, defense attorneys filed an unsuccessful motion to have the charges dropped, and the case has been crawling through the courts since.

McCarthy’s defense attorney Melinda Thompson, a former prosecutor, says her work on this case has convinced her that shaken baby syndrome is not a reliable diagnosis. “I was a prosecutor in that office for seven years,” she wrote in an email, “I never prosecuted child abuse cases and never thought about SBS cases. I should have. I am appalled that this can happen. I won’t stop until Aisling is free.”

In the petition filed last week, Thompson and co-counsel David Meier argued that Rehma had a complex medical history, including a bleeding disorder, which Dr. Alice Newton at Boston Children’s Hospital did not consider before making the abuse diagnosis. The petition also cited the case of Geoffrey Wilson, accused in 2010 of shaking his 6-month-old son to death. The state medical examiner has recently derailed that prosecution by amending the cause of death from homicide to undetermined. The shaking diagnoses in both Wilson’s and McCarthy’s cases were made by Dr. Newton.

“Medical Child Abuse”

Justina Pelletier’s parents brought their daughter to Boston Children’s Hospital on the advice of Dr. Mark S. Korson, a metabolic disease specialist at Tufts Medical Center who had been treating Justina for mitochondrial disease, a rare and little understood condition that includes muscle weakness and digestion problems. Her health was failing, and Dr. Korson wanted her to see her long-time gastroenterologist, who had moved from Tufts to Boston. But the child protection team at Boston Children’s, led at the time by Dr. Newton, concluded that the girl’s symptoms were psychosomatic, triggered in part by her family’s insistence on receiving what they considered “unnecessary medical treatment.” The courts accepted the doctors’ diagnosis of “medical child abuse” and removed Justina from her family. The hospital then placed Justina in a locked psychiatric unit and allowed her only one supervised visit and one supervised phone call each week with her family.

“No one was on my side there,” Justina told Mike Huckabee at Fox News in a televised interview after her release. “No one believed me there. They all thought I was faking.”

The relationship between the Pelletiers and the hospital remained hostile, and in March of 2014 a judge granted permanent custody to the state of Massachusetts, in an opinion that criticized both the Pelletiers for their refusal to cooperate with Justina’s new treatment plan and the state of Connecticut, where the family lives, for its failure to get involved.

Justina’s health did not improve, though, and in May of 2014 she was transferred to a residential treatment program in Connecticut, closer to her family. The staff at the new facility found the Pelletiers “cooperative and engaged,” and in June the same judge authorized Justina’s return home. The order returning custody to the Pelletiers did not explicitly reject the diagnosis of “somatoform disorder,” or illness caused by psychological issues, instead noting that “circumstances have changed” since Justina became a ward of the court.

Since her release, Justina, her family, and their advocate Rev. Patrick Mahoney have made a number of public appearances, including a Congressional address and a televised press conference, and the case has been offered as an object lesson by both alternative health care activists and the mitochondrial disease community.

When attorneys for Aisling McCarthy filed their motion in the shaking case, Boston Herald columnist Peter Gelzinis apparently hit a nerve with an opinion piece noting that the Pelletier outcome had tarnished the credibility of the diagnosing physicians: His column triggered a cascade of public comments about false allegations of child abuse in Massachusetts.

Unlike the infants Matthew Eappen and Rehma Sabir, Justina Pelletier was 15 years old when she arrived at Boston Children’s Hospital, old enough to tell doctors that her parents were not abusing her. She already had a diagnosis of mitochondrial disease from a reputable institution, and she continued to insist that her symptoms were real, while her health continued to unravel. “They didn’t care,” she told Mike Huckabee, “They were saying that I was improving, which I was not.”

Some medical conditions, like cancer or tuberculosis, can be confirmed by testing. The tests might have a known error rate, the likelihood of a false positive or a false negative, but guidelines and data are available. There is no test, though, to confirm or reject either shaken baby syndrome or medical child abuse. Doctors are relying on what they’ve been taught about the conditions, supported by their clinical experience, which of course incorporates the opinions of their peers and courtroom outcomes.

According to press reports, there is also no definitive test for mitochondrial disease, which mired the Pelletier case in uncertainty from the beginning. Before the case resolution, Brian Palmer at Slate speculated in an essay emphasizing the ambiguities:

Linda and Lou Pelletier may be the innocent victims of an all-powerful hospital that followed a misdiagnosis to its painful and damaging end. Or perhaps they are sick people who have tortured their daughter with unnecessary medical procedures. They could even be both—the parents of children with mitochondrial disease often suffer from the same disorder, which can cause emotional and psychiatric problems.

In the Pelletier case, time offered a test of the doctors’ hypothesis: After sixteen months of psychiatric care and separation from her family, Justina’s legs are so weak she uses a wheel chair to get around, and her parents say she has regressed academically.

But time has few opportunities to prove or disprove a diagnosis of inflicted head trauma. Infants who survive presumed shaking assaults routinely suffer from seizures and other neurological complications: The common knowledge is that these problems are a result of the assault, and not a clue to an alternative explanation for the initial collapse. Similarly, infants diagnosed as shaken often arrive at the hospital with both old and fresh bleeding in their brains. Child abuse physicians conclude that these children have been shaken in the past and then again just before they became symptomatic—although I’ve never understood why this explanation doesn’t interfere with the presumption of immediate symptoms.

In rare cases, the medical records ultimately reveal an underlying condition—like sickle cell disease in the case of babysitter Melonie Ware or Menkes syndrome in the case of Tammy Fourman—but no one knows how many other disorders might cause the brain bleeding and swelling that’s routinely ascribed to shaking, and as the McCarthy motion points out, doctors seldom test even for the known causes.

So the courts are left to arbitrate between the doctors who believe they can know from the brain findings that a child was shaken and the caretakers who claim innocence. I can only hope that further research and improved technology offer better answers soon, because I believe that innocent people are being accused and benign families torn apart by sincere physicians working with a theory that pushes well beyond the limits of what’s really known.

The McCarthy motion asks for a hearing to scrutinize the science behind shaken syndrome under the “Daubert-Lanigan” standards that govern expert testimony. If that hearing happens, I hope the Boston press will stay with the story.

copyright 2014 Sue Luttner

If you are not familiar with the debate surrounding shaken baby syndrome, please see http://onsbs.com.