New Family Trees: Lessons from the Donor Sibling Registry's First Decade

Wendy Kramer did something radical in 2000. Prompted by her own experience as a mother who had given birth to a child with the help of a sperm donor, she created an online, voluntary registry system for the children of egg and sperm donors. It was a small operation at first, but then Good Morning America broadcast a piece about it. Then Oprah did the same. Soon it was drawing a community not only of thousands of donor-conceived children but of the donors themselves. The Donor Sibling Registry was created before Facebook made it simpler for lost friends and relatives to find each other, before LinkedIn allowed us to peer into each other’s resumes with ease, before smartphones made it easy for us to track down a million pieces of information (and to freely give ourselves up to being tracked) while walking to a coffee shop. A decade later, Kramer’s radical experiment seems more like part of the accepted fabric of our modern, private-made-public experience.

In December, Kramer and Naomi Cahn, a family law professor who teaches at the George Washington University Law School, will release a very compelling book – Finding Our Families -- about what they have learned about donor families since the Donor Sibling Registry was launched and how that combined knowledge can be used by, as they put it, “donor-conceived people and their families.” And they show throughout how fertility medicine and the family dynamics created by it are still attended with a lot of misunderstanding, secrecy and shame. There are comments throughout from children, parents, and donors. The audience is primarily the families in the title, but the book offers a wide variety of ideas for journalists, too. Below are lessons I drew from the book, and in a subesquent post I will write about some ideas that Kramer and Cahn offer for changing the way fertility medicine is managed. Some of those ideas would still qualify as radical.

Respect self-identification. Within the first few pages, Kramer and Cahn describe how tricky it is even to write about sperm and egg donation. When someone adopts a child in 2013, they almost certainly never refer to them as their “adopted son” or “adopted daughter,” terms that were more common decades ago. They become family, often even before any legal papers are signed. Similarly, children who are born because of egg or sperm donation don’t necessarily want to be labeled “donor children.” Or, conversely, they may want to make clear distinctions about the parents who raised them versus the person whose chromosomes they share. Kramer and Cahn write:

Chuck, whose parents used donor sperm, explains: “The one term I have a great deal of trouble with is ‘donor’. This man did not ‘donate’ anything. He sold his sperm. ‘Donation’ means giving something to someone for a good cause or the act of giving to a charity. I do not have a donor. I have a biological father.”

Help children trace their health history. I did this for a story in the Los Angeles Times, and it was one of the most difficult stories I have ever reported. I tracked down an egg donor to report on how a pair of fathers and a surrogate mother had given birth to a child with a severe genetic disorder, the kind that is not routinely tested for in donor screenings. These are compelling stories and there are many more of them out there. Cahn and Kramer quote a mother named Rebecca who traced a genetic disorder through her son’s donor.

I found my son’s donor in 2008 and discovered that he suffered an aortic dissection in 2007 and nearly died. It turned out to be a genetic defect in the connective tissue of the aortic root. His two brothers and his mother also had the same problem. When my son was checked, he also had the same heart defect. His open-heart surgery to correct the problem was in June of 2010. Thanks to the [Donor Sibling Registry], I was also able to alert the parents of the five known half sibs. I was also able to find the two other clinics where the donor donated and alert them.

Don’t expect tracking down donors to be easy. You may have to make use of birth certificate records, death certificate records, social media pages, and gumshoe. Kramer and Cahn write about a woman named Kathleen looking for her sperm donor. Kathleen knew two things about her donor: he had been a Baylor Medical School student and he likely had blond hair.

In 2006, she went to Baylor’s med school library and pored over yearbooks from 1979 to 1984. In the beginning, she was naïve enough to think he’d jump right out. She paid close attention to eyes and smiles. She photocopied the pages and asked friends to flip through them and star the best candidates. Before she knew it, she had come up with a list of six hundred candidates, whom she alphabetized and stuck into binders. She sent letters to all six hundred of them and received responses from almost half.

She has yet to find her donor, but don’t let that discourage you from reading this book and from using it to spark your own journeys into writing about donation.

Next: Should the donation industry be under tighter controls?

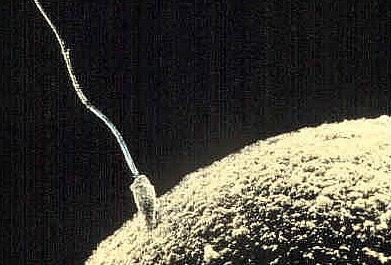

Image by Andrea Laurel via Flickr