New FCC Journalism Report Paints Bleak Picture of Health Coverage

The long-awaited Federal Communications Commission report on American journalism, Information Needs of Communities, paints a poignant, if slightly dated, picture of the decline of health journalism at the nation's newspapers, even as it highlights some of the online ventures that have stepped into the void.

Losing journalists who cover such a specialized beat as health is significant. Reporters often spend years building up an expertise in the intricacies of medicine. They must learn how to decipher, explain, and put in context complex, confusing, and often controversial developments in treatment and cures, breakthroughs and disappointments. They need to translate medical speak into plain English. They need to be on top of developments in such areas as pharmaceuticals, clinical testing, hospital care, infectious diseases, and genetics. Theirs are not the kinds of stories that other reporters can easily produce.

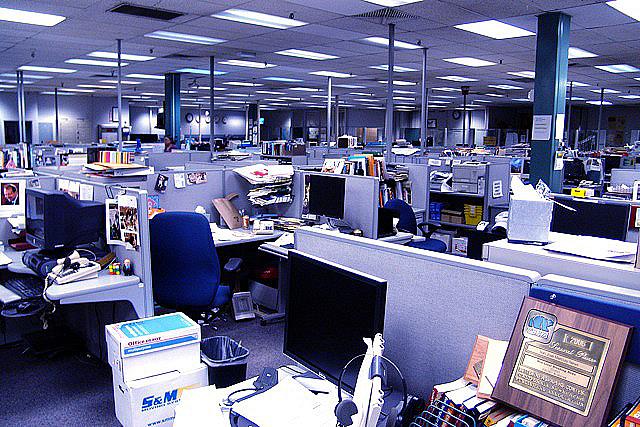

I should note that I personally experienced this decline when I was laid off from the San Jose Mercury News in 2008, after covering health and medicine for the newspaper for eight years. I was never replaced, and today the Mercury News (that's its newsroom in the photo) remains one of the largest newspapers in the nation without a full-time health reporter. At other media outlets, the health beat is simply added to the daily responsibilities of other reporters who may be covering education, science, the environment or local government - a trend that our California Endowment Health Journalism Fellows have shared with us.

Journalist Amy Gahran analyzed the FCC report for CNN, while the hyperlocal news industry publication StreetFight chastised the FCC for backwards-looking solutions to the problem of watch-dogging community government and services with fewer journalists. I especially liked Eric Mack's summary of the report for CNET:

If forced to sum up the entire report in a single tweet, it would probably be "The Internet has revolutionized how we gather and consume information, but meanwhile local news has been damn near suffocated.

So that you don't have to go look it up, I've excerpted the FCC report's health journalism section (without the footnotes, thankfully). I welcome your thoughts in the comments below.

A March 2009 report, entitled The State of Health Journalism in the U.S., produced for the Kaiser Family Foundation, found that the number of health reporters has declined even though reader interest in the topic remains strong. Fewer reporters are doing more work, resulting in "a loss of in-depth, enterprise and policy-related stories." The report, by Gary Schwitzer, an associate professor of journalism at the University of Minnesota, concluded:

"Interest in health news is as high as it's ever been, but because the staff and resources available to cover this news have been slashed, the workload on remaining reporters has gone up. Many journalists are writing for multiple platforms, adding multimedia tasks to their workload, having to cover more beats, file more stories, and do it all quicker, in less space, and with fewer resources for training or travel. Demand for ‘quick hit' stories has gone up, along with ‘news you can use' and ‘hyper-local' stories.

"As a result, many in the industry are worried about a loss of in-depth, enterprise and policy-related stories. And newsrooms with reduced staff who are facing pressure to produce are more vulnerable to public relations and advertising pressures. Health news may be particularly challenged by the issues of sponsored segments, purchased stories, and [video news releases] VNRs."

While specific figures are not available to track newspapers' reduction in health reporters, the Kaiser report said that, in a survey of members of the Association of Health Care Journalists, 94 percent of respondents said that "bottom-line pressure in news organizations is seriously hurting the quality of health news." Further, 40 percent of journalists surveyed said that the number of health reporters at their outlets had gone down during their tenure there, and only 16 percent said the number had increased. In addition, "39 percent said it was at least somewhat likely that their own position would be eliminated in the next few years."

Losing journalists who cover such a specialized beat as health is significant. Reporters often spend years building up an expertise in the intricacies of medicine. They must learn how to decipher, explain, and put in context complex, confusing, and often controversial developments in treatment and cures, breakthroughs and disappointments. They need to translate medical speak into plain English. They need to be on top of developments in such areas as pharmaceuticals, clinical testing, hospital care, infectious diseases, and genetics. Theirs are not the kinds of stories that other reporters can easily produce.

In 2009, Ferrel Guillory, director of the University of North Carolina's Program on Public Life, explained in a North Carolina Medical Journal article how the latest staff reductions had impacted health reporting at one paper. "Only a few years ago," he wrote, "the News & Observer in Raleigh had as many as four reporters assigned to various health-related beats. They covered the big pharmaceutical industry in Research Triangle Park, Chapel Hill-based Blue Cross Blue Shield, the medical schools of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University, and local hospitals. As of August 2009, the N&O has only one reporter with a primary focus on health."144 Guillory concluded that, although the appetite among the public for health stories remained high, "dependable, continuous" health coverage had diminished. Further, he wrote, journalists (in particular, those on television), focus more on emergencies, public health "scares," and the announcements of new "cures" and technologies than on important policy matters and major trends in health and health care. Mark Silverman, editor of the (Nashville) Tennessean recalls the day he stood with a staff researcher in front of a blackboard listing major stories he had hoped the paper would produce in the coming months. One line listed a story about how the state medical board was allowing incompetent doctors to mistreat patients, be disciplined by local hospitals, and then continue practicing medicine at other locations. But that story idea had an "X" next to it, meaning it would not get done, because the paper now had one health reporter instead of two.

While doing research for a book, Maryn McKenna, a former health writer for the Atlanta Journal Constitution, made an astonishing discovery: The "flesh-eating disease"-MRSA, or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-was rampant at Folsom Prison in California. In an average year, the highly contagious skin infection kills 19,000 Americans, puts 370,000 in hospitals, and sends an estimated seven million to doctors or emergency rooms. "Some guards are getting infected, seriously infected," McKenna says. "When prison guards go home, they take MRSA with them." Now, families and friends, wives and children, the convenience-store clerk who hands over change or a lottery ticket are susceptible to the infection, which easily spreads outside the prison into the general and unwitting population. At the time, MRSA had been described in the national and specialty press, but no one had written about the situation at Folsom. "I just kept thinking, ‘I can't believe nobody's written about this,"' McKenna says. "Why hasn't it been in the L.A. papers, in the San Francisco papers? It's not like those are lazy institutions." She then realized that, as at many newspapers large and small, deep staff cuts had left them unable to cover the story. The crisis went unnoticed until McKenna wrote about it.

Even when they are able to cover a medical story, time-strapped reporters often miss significant pieces of information. In the Kaiser study, more than 75 percent of the 500 stories reviewed concerning treatments, tests, products, or procedures failed to adequately discuss cost. And more than 65 percent failed to quantify the potential benefits and dangers, according to HealthNewsReview.org, a website created by Schwitzer, the author of the Kaiser study.

In the report and on HealthNewsReview.org, complaints abound from seasoned reporters who lament the growth of "press release reporting" and the lack of time they have to check out the veracity of information contained in a press release. Twenty eight percent of health reporters said that they personally get story ideas from public relations firms or marketing outreach somewhat or very often. Among those who work on at least some web content, half said that having to work across different media has resulted in less time and attention for each story, and 59 percent said it meant that they work longer hours.

In an attempt to replace some of the health coverage that disappeared from newspapers, the Kaiser Family Foundation in late 2008 created a nonprofit news service that would produce in-depth coverage of the policy and politics of health care. Kaiser Health News (KHN) hires seasoned journalists to produce stories for its website, KaiserHealthNews.org, and for mainstream news organizations.

Drew Altman, president of the Kaiser Family Foundation, explained to the New York Times why Kaiser Health News was a top priority: "I just never felt there was a bigger need for great, in-depth journalism on health policy and to be a counterweight to all the spin and misinformation and vested interests that dominate the health care system," he said. "News organizations are every year becoming less capable of producing coverage of these complex issues as their budgets are being slashed." In addition to KHN, a number of smaller nonprofits have emerged to provide health care reporting in various states.

Photo credit: Martin Gee via Flickr