One Child Is Too Many: Five Tips from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch's Deadly Day Care Series

In health reporting, few things are as emotionally draining and as logistically difficult as writing about a child who has been victimized.

In health reporting, few things are as emotionally draining and as logistically difficult as writing about a child who has been victimized.

Everyone has been a kid, and many reporters have kids of their own. When you come across a document that describes how children have been hurt or killed by someone who was supposed to be protecting them, one of your instincts is to put it back in its place and look for another story.

If you are a reporter as good as Nancy Cambria, you keep digging. Cambria started reporting on a child who died at a home day care in Missouri in 2008 – Nathan Blecha, 4 months old – at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. She turned what could have been a tragic but isolated event into a can't-put-it-down series.

Here are five tips to be taken from her work.

1. Define local. The mantra for newspaper survival over the past decade has been to go hyperlocal. When doing an investigation with this scope, though, the findings become meaningless without some state-to-state or national comparisons. How does a local reporter, though, find the time or the resources to do that national-level reporting? Cambria did just enough to be able to write with authority:

The investigation further found a systematic failure in Missouri to prevent the deaths, rooted in some of the weakest child care regulations in the country. Missouri's child care oversight is so inadequate that state regulators lack the information and the authority to address the problem. That's because the vast majority of deaths occurred outside the reach of state oversight, typically in unregulated home day cares. Of the 35 sleep-related deaths in child care, all but four occurred in unlicensed day cares. There are no inspections in such settings, and caregivers are not required to meet simple sleep safety standards that have been credited with saving lives in other states.

2. Know when your methods are relevant. It's always tough to decide how much of one's reporting to actually show in the final product. Cambria found that the way she reported the story revealed much about the way day cares are allowed to operate without oversight or serious repercussions in Missouri. Cambria writes about Julie Clifton, who was told that her child, Nathan, had died of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), which normally is applied to cases where the death is a mystery with no apparent cause. Cambria writes:

SIDS should not be the finding when known sleep hazards are present, including placing infants to sleep on their abdomens, some experts say. The Cliftons read the term SIDS and assumed there had been no way to prevent Nathan's death. So they stopped asking questions of police. In June, the Post-Dispatch provided Julie Clifton with a copy of the police report on Nathan's death. She said nobody - not the caregiver, not the police, not the medical examiner - had told her that Nathan was found with his face in a pillow.

3. Ask how many matter. Anytime I give a talk about reporting, I talk about finding the investigations that are going to have a broad impact on a lot of people. It's why I write so much about medical board oversight, because nearly everyone ends up seeing a doctor at some crucial point and most medical boards are failing the public in multiple ways. Cambria could have looked at the number of deaths she was able to identify in child care centers in Missouri – 45 from 2007 through 2010 – and decided that the impact was not broad enough. But how many child deaths should be tolerated? Day cares have some fairly simple rules to follow, and, from Cambria's findings, most of those 45 children would still be living today had the providers simply watched fewer children at a time and paid attention to how the children were put to sleep. She writes:

Tyler was among 41 children who died from 2007 through 2010 in day cares not regulated by Missouri. The deaths typically occurred in home-based facilities, where many providers are exempt from needing a state license because they care for only a handful of children. But the deaths of Tyler and seven other babies were different. Each occurred in home day cares where providers were trying to watch as many as a dozen children on their own, creating a breeding ground for accidents. The eight deaths point to a system in which providers can easily and repeatedly skirt rules, enrolling far more children than allowed in unlicensed facilities. Four of the deaths in illegally unlicensed day cares involved providers who previously had been caught breaking this child care law - sometimes multiple times. None was punished. All went on to take on too many children again. And then a child died in their care.

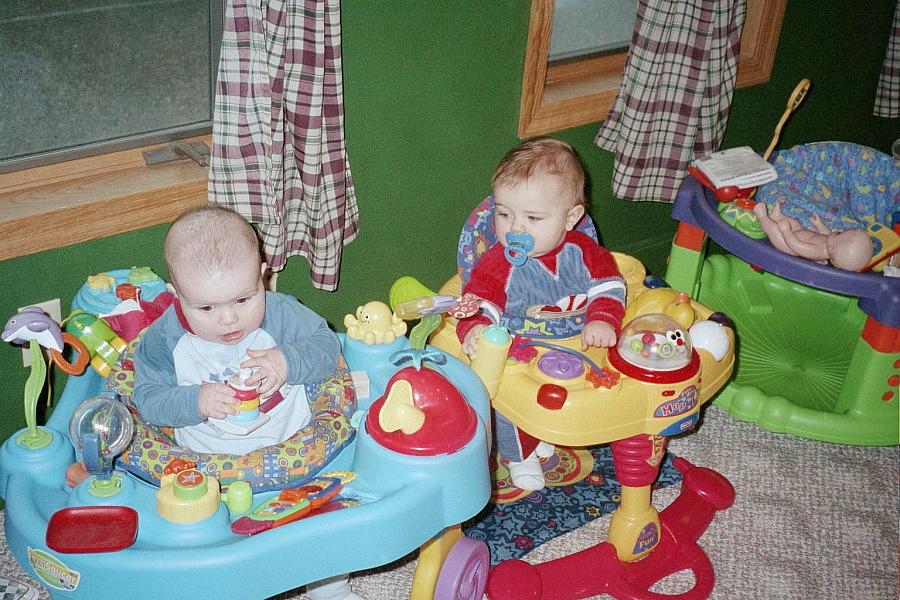

4. Write with a clear eye. As you can see from the excerpts above, Cambria writes descriptively and forcefully but without a lot of emotion. This can be a huge task when writing about kids being harmed and killed. The tendency is to want to include every last adorable detail about the children before delivering the blow that they were ripped out of their family's life in an instant. Cambria does provide some details about the families in her stories, but she mostly keeps her stories focused on the problems with the system. To accomplish this, she personalizes the families in other ways. When you click on the name of a child in the story, for example, a box pops up with the basic details of the child's case and a link to a story about the child and, in some cases, a video. And, if you really feel like crying today, click on this page with photos of many of the children.

5. Fight for disclosure. If you really want to turn those tears into anger, though, pay attention to how many babies on that same page don't have names: fully one-third. Throughout the series, Cambria documents the problems with the fractured, often anonymous way that complaints about day care providers are captured. She writes:

The Post-Dispatch attempted to do what Missouri's child care system has not - provide a clear and public accounting of deaths in child care. The newspaper compiled public documents on the 45 known cases, piecing together the identities and circumstances in as many of the deaths as possible. Information on those deaths was filed in separate state and local offices. Details often were not shared with regulators or the public. As a result, in 15 cases, the name of the child and child care provider were not released. The system makes it nearly impossible for parents considering day care in Missouri to determine whether a child has died in a facility - or whether most providers follow proper safety standards.