A Public Death: Knowing What Caused a Stroke Makes a Difference

We don’t know for certain how many people are dying from different types of strokes in the United States, in part because nobody is checking.

One of the most fascinating findings from the recent study in the journal Stroke about the poor classification of stroke deaths is this tidbit about “cause-of-death querying.” You may have never heard of this before, but the journal article’s authors explain it this way:

Cause-of-death querying as defined by the National Center for Health Statistics is a process by which the state health department contacts the medical certifier who completed the cause of death statement and asks for clarification or further information so that the resulting mortality statistics may be as complete and accurate as possible. However, according to a survey of state health departments in the United States, the median number of records queried for cause-of- death issues by registration areas was 5%, with areas in the lowest quartile querying approximately 1% and areas in the highest quartile querying [less than or equal to] 10%.

Remember, these researchers found that in 53% of stroke deaths, the medical certifier did not specify whether the stroke was infarction or hemorrhage on the death certificate, and in some states, the percentage of unspecified stroke death was as high as 64%.

So, more than half the time, stroke deaths are not properly classified. State health departments could double-check some of these vaguely worded death certificates to get the true cause of death, but that happens no more than 10% of the time and as infrequently as 1% of the time.

Why does any of this matter?

Because the differences in the mechanisms that cause strokes matter. I broke the four types down on Friday. Here I’ll offer a few examples of why being specific in each case matters.

Ischemic strokes (also called cerebral infarctions) are strokes caused by blood clots. If a person dies during a surgery or shortly after a surgery, and the physician calls it a “stroke,” it is anyone’s guess whether the two events were related. But if the stroke is identified as being a cerebral infarction, meaning a blood clot, we have made a stronger link. If a hospital knows that it has a problem with post-operative strokes, it can take steps to minimize those risks. A team from The Johns Hopkins University studied 5,971 patients who had undergone cardiac surgery and wrote in 2001 in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery:

The profound impact of stroke after cardiac surgery is demonstrated by a nearly fivefold increase in hospital mortality (19% vs. 4%), a more than doubling of intensive care unit and postoperative length of stays, and a $30,000 increase in total hospital charges.

If the stroke was a thrombotic stroke, it was caused in part by narrowing of the arteries from too much cholesterol or other factors. Understanding how many people are dying from strokes caused by narrowed arteries helps elevate awareness of the acute nature of the problem and direct policies toward the right problems. We already know that we have an obesity problem, but there’s not a lot of evidence that people are doing much about it. Part of this is because of confusion about weight gain versus heart disease. You can be a very healthy person in most aspects of your life and still have high cholesterol. So watching what you eat has important consequences beyond your waistline.

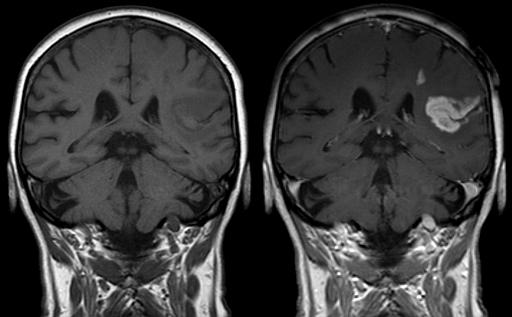

Now we get to the hemorrhagic strokes. As the name implies, this means bleeding, not clotting. If a person dies from an intracerebral hemorrhage, blood pours into the brain. High blood pressure is the top cause, and, like obesity, it’s a problem we talk a lot about but don’t necessarily address. We tend to think of it as a problem you don’t have to worry about until you’re in your 60s or 70s.

Researchers writing in Stroke in 1998 studied 200 patients who had suffered an intracerebral hemorrhage. They had had an average age of 27 and ranged in age from 15 years old to 40. They found that high blood pressure was a major risk factor but in nearly half the cases, a “vascular malformation” was the culprit. These usually can be identified with an MRI. Gary Schwitzer would kill me if I recommended blanket screening for all people aged 15 to 40, so I won’t. But I will say that if we were correctly identifying intracerebal hemorrhages in a significant number of deaths in young adults over time, a strong case could be made for revising prevention and screening guidelines.

The last main type of stroke is the subarachnoid hemorrhage. Here blood has leaked between the brain and the skull. Smoking increases the risk of having this type of stroke, as does the use of blood thinners. This is one of the biggest reasons for understanding what is actually causing a stroke. Blood thinners might be helpful in preventing one type of stroke – ischemic stroke – but they also have the potential of causing another type of stroke – hemorrhagic stroke. A truer count of stroke deaths would undoubtedly help pinpoint what is driving them and help us better prevent strokes.

I asked Larry Husten, one of the smartest writers on heart health that I know, about the Stroke study. He underscored the point that we should think about ways to make cause of death data more accurate.

Death certificates and records are notoriously unreliable and inconsistent when it comes to cause of death, especially when it comes to a death from a long-term chronic illness. About half of heart failure patients die from sudden cardiac death, but the clear underlying cause is the heart muscle. But the way this gets recorded can vary widely, and the experts will disagree about how it should be labeled.

I agree. I’d love to hear your thoughts, too. Send me a note at askantidote@gmail.com or via Twitter @wheisel.

Related Content:

A Public Death: Preventing Strokes by Improving Vital Statistics

If Hospital PR people offer heart scans, should journalists bite?

What Doctors Don't Know & Journalists Don't Convey About Screening May Harm Patients

Photo credit: Hellerhoff via Wikimedia Commons