Public Records: Marshall Allen on Why Journalists Should Play By Bureaucrats' Rules

Marshall Allen has made his name as an investigative health reporter by digging into public records.

He co-authored Do No Harm, an investigation into the Las Vegas hospital system in 2010 and one of the most thorough pieces of reporting ever done by a newspaper on its local health care system. The smart team at ProPublica must have been similarly impressed. They snatched him up earlier this year, and he now is reporting (and tweeting) from New York. (He wrote a great piece in June about Heart Check America.)

So when he told me last week that my anti-FOIA stance seemed counterproductive, I listened. I thought what he had to say was so compelling that I wanted to share it with you. Here's his guest post below.

When I lived in Kenya, it could take hours of waiting in unnecessary lines, filling out needless forms and getting stamps of approval just to pick up a package from the post office. It was a colossal waste of time. But it was the way they operated, and if you wanted your package you had to do as they told. Arguing about it only prolonged the pain.

Sometimes I compare this developing world madness to the process of obtaining public records from government agencies here in the States. Some of them have rules that seem to make no sense, but the people at the bottom of the food chain are obligated to obey them, no matter how ridiculous, lest they get squashed by the middle managers above them, who themselves are being pressed by the supervisors who check to make sure everyone is following the rules. No one likes the bureaucracy, least of all the people suffering at the bottom of it.

For this reason, I try to take an empathetic approach with the people who process my public records requests. Assuming they are willing to abide by the public records law, I don't worry about the formalities of how they want me to make the request. And no matter how frustrating, I try to avoid fighting them, arguing with them or creating an adversarial relationship. The people helping me are likely powerless, so it makes no sense to insist they change the process. If they ask me to jump through various hoops, submit requests formally, cite laws, etc., I do my best to abide by their bureaucracy.

My hope is that if I'm friendly and likable and sensitive to the pressures being applied to the bureaucrats at the bottom of the totem pole, they might just do that other thing that's always possible in bureaucracies – bypass the standard hassle so that I can get my request processed smoothly.

This approach helped enormously in obtaining the inpatient hospital data that became the foundation of our "Do No Harm" project at the Las Vegas Sun.

I had built up a good relationship with the state Department of Health & Human Services in Nevada, which started years earlier when I took an off-deadline trip up to their offices in Northern Nevada to introduce myself and learn about the way their office operated. No one had ever made a public records request for that dataset. It was about 2.9 million electronic files that documented every inpatient stay in a Nevada hospital over a decade. We had to fill out a lengthy data use agreement to obtain that data, and it required us to abide by certain restrictions related to patient privacy.

Their policy stated it would cost around $7,500 for the data. We politely argued that we should get the data for free, since were doing a public service and not selling our analysis for profit. We pointed to our previous track record of data analysis and careful journalism as evidence that we would treat the data with integrity. Thankfully, they approved our request and gave us the data for free.

Getting that request granted led to our analysis and stories, which a year later resulted in five new patient safety laws in Nevada during the 2011 legislative session. We had to jump through hoops, and it took weeks, but the effort paid off.

Whether you start working with an agency with a formal request or an informal one, if you aren't getting the records in a timely manner, you should press them to abide by the law. You need to be persistent about following up to make sure the request is processed. In order to do this, you need to know the state or federal law yourself. I also am in favor of reporting any resistance to public records requests. Public shaming is a great way to go, and that can apply pressure at the top of the agency, where it can be most effective.

I fully believe that we should not be required to cite any laws to see public records. It's our right under the law to see them, and they should be readily accessible. But fights about fairness may be more constructive at a different time, like the way the Association of Health Care Journalists and other journalism organizations have met with the heads of agencies to discuss access to public records. I think conversations are more productive at that level.

Just remember when you make your request that the person on the other side of the counter or on the other end of your email may hate the rules just as much as you do. And whether it's the Nairobi post office or the Department of Health & Human Services in Nevada, going in with a smile never hurts.

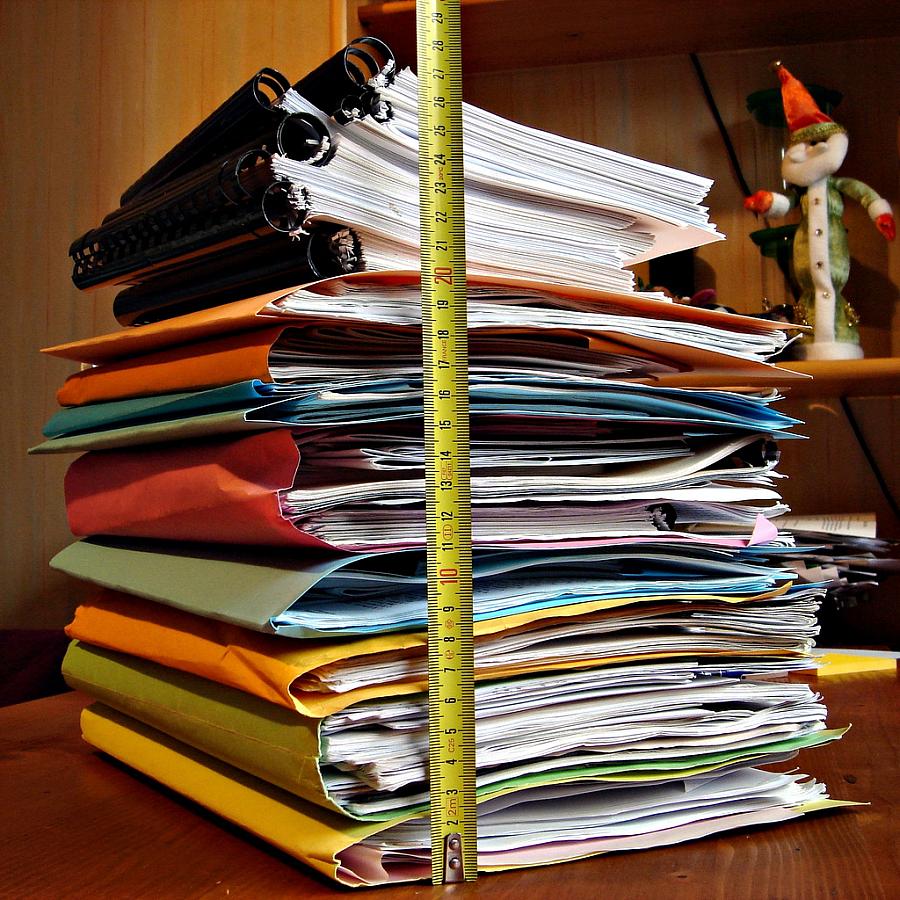

Photo credit: Alexandre Duret-Lutz via Flickr