Putting Valley Fever on the Front Burner

How does knowledge about unfamiliar diseases enter the public consciousness and the public policy agenda?

As editor of Reporting on Health, I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about this question as we launch a series by a new reporting collaborative I brought together. It includes news outlets whose reporters have participated in our California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowships. Reporting on Health Contributing Editor William Heisel has ably served as project editor for this effort.

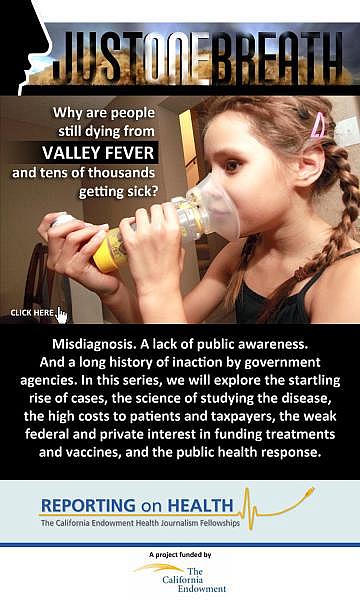

The series chronicles the terrible toll of valley fever, a disease found throughout the Southwest, including California’s San Joaquin Valley. Valley fever has reached epidemic levels in California's Central Valley. It is woven through the fabric of people’s lives – everyone there knows someone with the disease – but it receives woefully little attention from policy makers, researchers and public health officials.

This devastating disease can be contracted when fungal spores lodge in the lungs after being swept up from the dirt by wind. Valley fever, or coccidioidomycosis, strikes more than 150,000 people nationally each year. In about 100 cases annually, the disease kills.

The news media perform their most fundamental public service by highlighting overlooked community concerns. Local reporters and editors involved with the Collaborative identified valley fever as a topic worthy of sustained and concentrated reporting attention. Stories on the issue will appear beginning Saturday, September 8 and continue as an occasional series over the next month in the Bakersfield Californian; the Merced Sun-Star; Radio Bilingüe; The Record in Stockton, Valley Public Radio and Vida en el Valle in Fresno; and the Voice of OC in Santa Ana. The stories also can all be found on our project micro-site on Reporting on Health.

Our Reporting on Health Collaborative found that valley fever causes more deaths than Hantavirus, hepatitis A, whooping cough and salmonella poisoning combined, yet all of these conditions are more widely known. Among my friends, for instance, everyone began talking about the hantavirus threat after the California Department of Public Health put out an advisory about cases in Yosemite National Park. News outlets all over the country then picked up that bulletin. Yet the incidence of Hantavirus – with eight confirmed cases and three deaths among Yosemite visitors as of this writing – pales in comparison with valley fever.

Competition for research dollars

Valley fever also receives only a fraction of the research funding that many other diseases receive. But valley fever isn’t the only ailment that has received the short end of the stick,

The winners of the research funding race include West Nile disease. The federal government spent $52 million on research on the disease in 2010, a year in which there were 1,021 cases and 57 deaths, for a per death investment of $912,280. That same year, it spent $2.54 billion for research on cardiovascular disease, which killed 595,444 Americans, according to preliminary data from the CDC, for a per death investment of $426. Heart disease is the leading cause of death in America.

But diseases like West Nile virus or hantavirus intrigue. Hantavirus seems exotic and newsworthy and provokes a profound sense of alarm because it is so fatal, novel and unexpected, theorizes Alexander Capron, my USC colleague and the Scott H. Bice Chair in Healthcare Law, Policy and Ethics. The prominence of the victims can be just as important when it comes to garnering public attention for a disease, he adds. So it’s not that surprising that California’s Central Valley, often overlooked in favor of urban centers, wouldn’t get needed policy attention around this issue.

We hope that the series helps those who suffer from the disease to feel less alone. Community can be healing and empowering. And when it comes to commanding resources for prevention or research, it can serve as a potent force for change.

“There is a vicious cycle of a disease not getting funding because it is not hitting a vocal or connected group of people,” Dr. Francine Kaufman, M.D. told me. A pediatric endocrinologist who is vice president of global medical affairs for Medtronic, Inc., she has had a distinguished career as a researcher, clinician and activist focused on diabetes in children.

“It needs a group to lobby for it, a patient association. The term is ‘to go HIV,’” she adds, “which means get all the people who have it or are at risk to make noise. This is what happens in cancer and diabetes. I don’t think there is a well-connected cocci patient group out there up in arms. The Central Valley is low on the totem pole for everything in this state and country.”

Starting a community conversation

We are taking Dr. Kaufman’s advice to heart. Our aim with this series is to start a community conversation around what needs to be done in public health and policy circles about valley fever. There is a role for everyone ranging from concerned locals to patients to health care providers, businesses and farm interests, community groups and non-profits.

The California Endowment, which funds our programs, including the Reporting on Health Collaborative, is encouraging this new direction. Mary Lou Fulton, a senior program manager, had a distinguished history as an innovator in community media before entering the foundation world. She finds great value in thinking of the publication of journalistic projects as a starting point not an end point.

We are learning as we seek to connect with community leaders in the San Joaquin Valley. And we are relying on the wisdom of friends, thinkers like Manny Hernandez, who has built a potent community around diabetes with Tu Diabetes, an international online community for people with diabetes. At a recent forum, Donna Hill, chair of the foundation board that governs the Tu Diabetes site, shared how she organized her friends from Tu Diabetes to successfully prod a major pharmaceutical company to renew its effort to take a promising diabetes treatment to market. It had placed that project on the back burner.

“Social networks no longer serve 'just' to keep us up-to-date about our friends and family,” Hernandez told me. “They have become agents of change, helping galvanize people around causes, from diabetes to cancer. There is growing evidence of the impact and improved outcomes that can be seen when people touched by the same medical condition connect with each other."

Or, as Susannah Fox put it to me, after studying online patient communities for years as associate director of digital strategy for the Pew Internet and American Life Project: “Altruism can scale.”

----------

Michelle Levander is the founding editor of Center for Health Journalism Digital and director of The California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowships at the USC Annenberg School of Jounalism.You can reach her at levander@usc.edu

Photo credit: Vida en el Valle