Q&A with Keith Hoffman: Keeping the FDA Honest with Adverse Events Data

My colleague here at Reporting On Health, Dr. R. Jan Gurley, reported last month that "a scrappy little start-up" called AdverseEvents, Inc. had embarrassed the FDA by showing that two epilepsy drugs on the market were likely more dangerous during pregnancy than their FDA-approved labels would indicate.

Intrigued, I asked Keith Hoffman, the vice president for scientific affairs at the company, to tell me a little more about how the company does its work and how reporters might learn from it. Hoffman started his career as a neuropharmacologist, with a PhD from University of California-Irvine, where he worked for Gary Lynch, the renowned memory specialist whose work was the subject of a lengthy series in the Los Angeles Times in 2007. He went on to work in executive posts for several startups in science, business development, and intellectual property roles. I reached him via email.

Q: Your scientific background is in neuropharmacology and memory. When you were working with Dr. Gary Lynch or in your roles at biotech companies, what types of experiences did you have with FDA adverse event information and its Medwatch database?

A: Really very little, other than what we all are exposed to via drug commercials, i.e. a laundry list of side effects that don't seem like tangible data points. I, like most people, assumed that the FDA must be hyper-vigilant about post-marketing side effects. I was, to put it mildly, surprised when Brian Overstreet, the CEO of AdverseEvents, explained what he and his colleagues had uncovered about the actual state of affairs regarding post-market adverse event reporting.

Q: Tell me more about what led to the creation of Adverse Events Inc. and what specifically brought you there?

A: Like many things, the company was created out of necessity. The company was founded in early 2010 by Brian and some of his partners from a previous business. They started AdverseEvents when the wife of one of Brian's partners suffered a serious side effect from a medication, and they couldn't find any relevant data on incidence or outcomes rates for that side effect. The only source of data they could find was at the FDA, but it was unstructured and not readily accessible. But, being in the data field already – at Sagient Research – they were able to download it and immediately understand how poorly structured and corrupted the FDA's database was. As they delved deeper into the FDA's data, they began to realize how big the problem was and how big the opportunity could be.

As for me, I've known Brian for a long time. We went to high school together in La Jolla and played football together. We lost touch for a while, but re-connected over wine. Brian and his wife own a small, not-for-profit winery called Bruliam Wines, and I'm a wine enthusiast. So, it was over one of many shared bottles of wine that Brian and I started talking about this idea. And the more I discovered about it, the more I knew it was something that I needed to be involved with.

Q: The idea that the FDA data are rife with errors will be surprising to many people. How did you discover that?

A: Discovering the errors really wasn't that hard. Once Brian and his initial team downloaded the data and tried to put it into a relational database, it simply didn't work. When they started looking at why it didn't work, they realized that there was no consistency in how data was being entered or maintained. It was a classic case of garbage-in, garbage-out.

Q: You mention on your website that some drugs can be coded 100 different ways in the FDA database. I am guessing this is an extreme case. Can you give me a few examples of the types of problems you have encountered frequently with the FDA data?

A: It's actually not an extreme case at all. The FDA has over 200,000 different raw drug names in its database. Using our RxFilter data refinement process, we've managed to reduce that down to about 4,500 true drug names.

For example, in the FDA's raw data there are 442 variations on the name Ambien. That includes generics, non-U.S. brand names, and every form of misspelling you can imagine. The problem is that there are adverse event reports associated with each one of those 442 different names. So, the only way to get a complete view of side effect problems with Ambien using the FDA's data is to know all of those 442 names and add together the side effect reports and outcomes for each of those. It's not something that can realistically be done manually.

To combat that problem, we developed a unique data sourcing method called RxFilter, which is a proprietary 17-step data refinement process that standardizes and normalizes the data from the FDA and converts into a an aggregated, fully searchable database.

So now when you come to the AdverseEvents site and search on Ambien, you get an aggregated report that includes the side effect information from each one of those 442 drug names.

Q: What do you think is leading to these errors in the data?

A: There are a number of reasons, but the primary one is that the database is free-form entry. Adverse events can be reported by manufacturers, healthcare providers, patients, or care-givers. Many of those reports are hand-written and faxed into the FDA. And, unfortunately, whatever is on those pages is what gets entered into the database. There is no standardization process at the point of entry. Unfortunately, when that's compounded across millions of side effect reports, the data becomes virtually unusable.

Q: Why isn't the FDA doing what your company is doing?

A: I don't really know. The only answer I can provide is that the FDA is understaffed and underfunded. You have a lot of very smart people over there trying to do a lot of things, and this just does not seem like it has been a priority of late. Given that the FDA database is supposed to be the primary source of adverse event information, we think major fixes need to be implemented, and fast. We are here to help them with that if they'd like.

Related Posts:

Adverse Events: Did a Scrappy Little Start-Up Just Embarrass the FDA?

Q&A with Keith Hoffman, Part 2: Crunching Drug Data for Reporters on Deadline

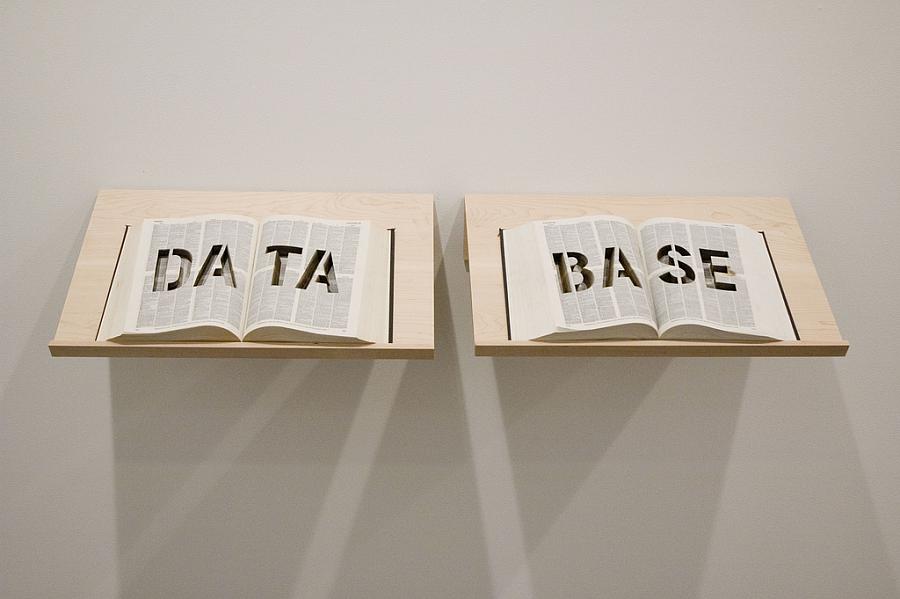

Home page photo credit: Michael Mandiberg via Flickr