Q&A: NPR’s Laura Starecheski reports on childhood adversity (Part 2)

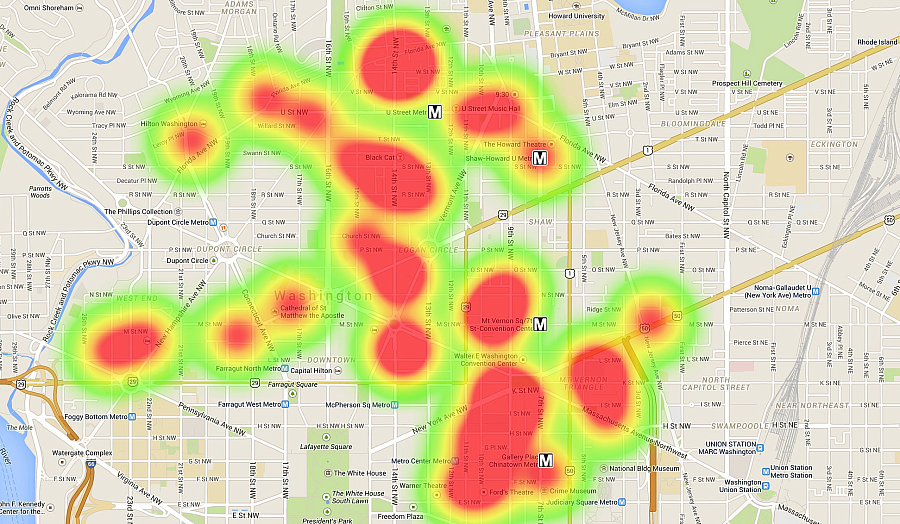

"There’s something about seeing a hotspot on a map — it really seemed to make people respond to the information in a different way," Starecheski says.

In March, NPR presented “What Shapes Health,” a series that included four deeply reported stories from NPR health reporter Laura Starecheski. Her stories explored how adversity, trauma and neglect experienced in childhood may influence life-long health patterns. Reporting on Health recently spoke to Laura about her reporting (read part one of this two-part interview here). The following has been edited for clarity and length.

Q. How did you find and select the programs and interventions focused on combatting trauma and childhood adversity that you highlighted in your stories?

A: In terms of finding the stories initially, I wasn’t necessarily looking for a proven success. I was really just looking for approaches that were innovative, and people who were willing to try something new.

There’s lots of interest in the ACE study in the fields of education, and juvenile justice, but I was interested in finding stories of people who were trying to use the ACE study, or the concept of ACE scores, to practice medicine differently. Once I found those people, then I could ask, “Do you have any data about what this has changed for your patients?” Mostly what I found, at least in the innovations I covered in the series, was that there just hasn’t been enough time to track patient outcomes yet. These innovations are new. And the issue of Adverse Childhood Experiences affects people over a lifetime, and it takes time – years, maybe decades – to figure out what might’ve changed.

So in general, the formula for me was: Find someone who’s experimenting and has a really interesting vision or idea, and then figure out how much you can track — in terms of what’s changed because of their idea. I think that’s a fun approach to health reporting.

I got some help getting started from researcher Emily Wilson, who made a very handy map of ACEs-related initiatives and research across the U.S. Talking to Wilson, and checking out her map, I realized that there is no cohesive national movement of innovation around the ACE study findings. People are going to be innovating most of the time locally – and the effects on outcomes will most likely be local too – so being able to zoom in on what’s happening in one particular place was a nice way to try to capture the ripple effects.

Q. Speaking of zooming in, one of your pieces tells the story of an innovative Florida doctor who teamed up with the local sheriff to map pockets of high poverty and trauma in Gainesville. The maps help officials better target needed services. What did you learn in reporting this story?

A: Something that struck me about Dr. Nancy Hardt and the maps she has — this wasn’t fully described in the piece — is that she takes her maps everywhere. She’s always carting around these big print-outs showing maps of Gainesville with all kinds of different hotspots marked: child abuse and neglect, domestic violence, unexcused absences in kindergarteners (a proxy for neglect, in Hardt’s view).

She takes these maps around town and talks to regular people about them. And something surprising happens: people tend to start trying right away to come up with a solution to the problem they see on the map. It’s really different from seeing a graph of, say, rates of abuse and neglect in Gainesville. There’s something about seeing a hotspot on a map — it really seemed to make people respond to the information in a different way. If you know Gainesville, you can see where families live, and maybe picture how they get back and forth to work. Something happens in your brain where you just start thinking, ‘Huh, I wonder what could be done to help those families specifically.’

The lesson for me as a journalist is: We need to use maps more! I know infographics are a big thing, and everyone is always trying to do better in terms of visualizing information. I think mapping is such a powerful way to do that. It definitely made me want to think harder about how we visualize problems and solutions in a way that’s very accessible to people who might not know or care initially about whatever issue we’re reporting on.

Q. You sat in as a patient talked to Dr. Vincent Felitti, co-author of the original ACE study, about the trauma she faced during childhood. Was it a challenge getting people to share such traumas on the record?

A: I think we’re at a moment where you’re seeing a lot of people, especially women, talk more publicly about childhood experiences like abuse or neglect. During my reporting, I reached out to a number of people who had high ACE scores, and I actually did notice that almost all the people I talked to were women. It was harder to find men who were willing to use their full names and go on the record. But, since I was fine with speaking to a woman for that story, it wasn’t that hard for me to find someone who would go in and meet with Dr. Felitti. I put out a call-out on Facebook, and got connected with a woman in San Diego who was willing to do it.

I think something else might have also helped: People want their doctor’s full attention. They want to feel like their doctor is listening to them. Oftentimes, doctors visits feel so rushed, and you don’t even know why doctors are asking the questions they’re asking. It seems like they’re never going to really get a full picture of your health — family history, mental health, physical health. I think that for many people, a sense that a doctor is gathering additional information feels positive. So I think the chance to get a very comprehensive medical history taken and then talk to a doctor about it felt like a useful experience for the patient in the story.

**

Related post

Q&A: NPR’s Laura Starecheski reports on childhood adversity (Part 1)

Cropped photo by Ted Eytan via Flickr.