Off the Record: Legislators try to put doctor discipline behind the curtain

Dr. John Perry has the type of history as a physician that patients might want to know about.

According to Washington state medical board records, he injured patients, had sex with a patient, failed to refer a patient to an oncologist when the evidence pointed that direction, and lied to the board.

You can find all of this out now by requesting information from the Medical Quality Assurance Commission. But, if state legislation currently under review goes through, this type of medical history will vanish from public review.

That’s because much of the long history of allegations of less-than-adequate and sometimes dangerous medical care by Perry has been handled informally by the commission. The technical term is Stipulations to Informal Disposition (STID), which the commission describes as “a document stating that allegations have been made, and containing an agreement by the licensee to take some type of remedial action to resolve the concerns raised by the allegations.”

This type of informal discipline occurs throughout the country in a variety of ways by medical boards. (Washington has a particular penchant for informal decisions, and I will write more on that in a later post.) Even if the discipline is often lighter in the cases of these informal agreements – as is the case with plea agreements in criminal matters – at least the records are public.

That could change. Legislators in Washington introduced two bills this legislative session -- one in the Washington state House and one in the Senate -- that would take the public records related to these agreements and make them private. Both bills appear to have stalled for now, but the session isn’t over for a few more weeks.

To understand what’s at stake, let’s take a closer look at what the commission found when it investigated Perry. It illustrates the range of behavior that could go on without public scrutiny.

Dr. John Perry practices obstetrics and gynecology in the eastern Washington Tri-Cities area. He was originally certified by the American Board of Obstetrics & Gynecology in 1990, but his certification has since lapsed.

Here’s the first part of a timeline of his recent troubles with the commission, according to the commission’s records. Note that Perry agreed to most of the facts in three out of the first five cases, according to commission records.

January 2004 - Perry removed a patient’s right fallopian tube and ovary. During the surgery, the patient’s small bowel was cut twice, and Perry repaired the cuts. Still, a few weeks later, she was admitted to a hospital with a bowel obstruction, and it was determined that was highly likely that the obstruction was due to the small bowel repair, according to commission records. The commission wrote that Perry:

…violated the standard of care in regard to Patient A by not calling in an experienced bowel surgeon when he lacerated the small bowel during the operation on January 21, 2004. He should have consulted with, and been assisted by, an experienced bowel surgeon from the onset of the problem. If not then, a consult and assistance most certainly should have been obtained when complications developed.

February 2004 – Perry operated on a patient who had a tear between her vagina and her rectum, but he did the operation too soon, according to commission records. The tear already had been repaired once, making it likely that a second surgery performed too quickly would fail. The commission found that Perry:

…violated the standard of care in regard to Patient B by performing this procedure too soon after the first repair, and without the assistance of a surgeon with appropriate expertise. He further violated the standard of care by not dictating his operative reports for almost two months after the procedure.

February 2005 – While operating on a patient, Perry found a tear in the patient’s colon. He repaired the tear without consulting with a general surgeon. Within 48 hours, the patient showed signs of an internal infection, but Perry did not do anything to treat the infection for four days, according to the commission. Then a CT scan showed that the patient had a bowel leak and generalized peritonitis. Still, more time elapsed. It was not until six days after the operation that Perry asked a general surgeon to weigh in. At this point, the surgeon had to take drastic measures, performing a laparotomy – which requires a major incision in the abdomen – creating a colostomy and draining an abdominal abscess. This required a long post-operative recovery, the commission said, adding that the patient was “extremely fortunate to have survived.” The commission wrote that Perry violated the standard of care:

…by not seeking a consultation with a general surgeon when he encountered surgical problems, and by delaying a surgical consult after the procedure when signs of sepsis were obvious.

In the commission’s stipulated agreement with Perry, it dropped the language about the patient being “extremely fortunate to have survived,” and instead wrote:

This injury would have been less significant, and possibly nominal, had [Perry] treated the situation as [Perry] now acknowledges he should have treated it.

After the experiences with the three patients described above, Perry made an agreement with the hospital where he had surgical privileges “that he would not use his privileges for bowel repair, and that he would consult a general surgeon, both intra-operatively and post-operatively, when there were issues concerning bowel complications,” according to commission records.

August 2005 – Perry performed a laparotomy to remove internal scarring from a patient. A few days later, the patient was readmitted with a small bowel obstruction, according to commission records. (Déjà vu?) And, as the commission found in previous cases, it decided later that Perry should have obtained advice from an appropriate surgeon earlier. The commission wrote that Perry:

…violated his agreement with the hospital and the standard of care in regard to Patient D by not obtaining a surgical consult with an appropriate surgeon until after August 17, 2005. This consult was not had until two days after he took over the patient’s care, and four days after the patient’s admission to the hospital.

In the commission’s stipulated agreement with Perry, he and the commission agreed “to make no stipulated findings of fact” regarding this patient, meaning her case was dropped from the final agreement.

December 2005 – Perry operated to remove scar tissue from a patient. This time he had another doctor with him, but, according to commission records, Perry did the surgery. The patient’s bladder and colon were injured during the surgery. Against the advice of a general surgeon, Perry tried to perform the repairs on her bladder and colon laparoscopically, meaning with a very small incision. The procedure lasted five hours and, according to the commission, “placed her at excessive risk due to the extended need for anesthesia.” The commission found that Perry:

…breached the agreement he made with the hospital as well as the standard of care in regard to patient E when he ignored the advice of the consulting general surgeon and he performed the repair laparoscopically.”

In the commission’s stipulated agreement with Perry, he and the commission agreed “to make no stipulated findings of fact” regarding this patient, meaning her case was dropped from the final agreement.

Note that the commission accused Perry of injuring five patients in less than a two-year span. And there’s more. I’ll write about that in a later post.

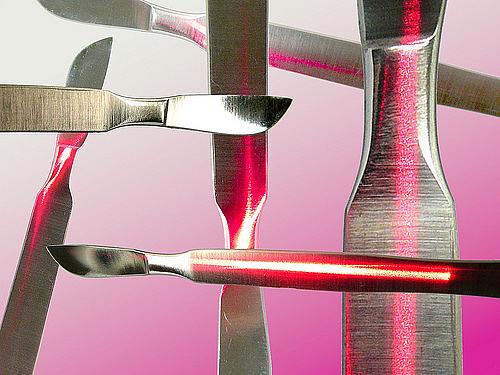

Image by OptoScalpel via Flickr