Reporters share how they’re covering the eviction story after court ruling

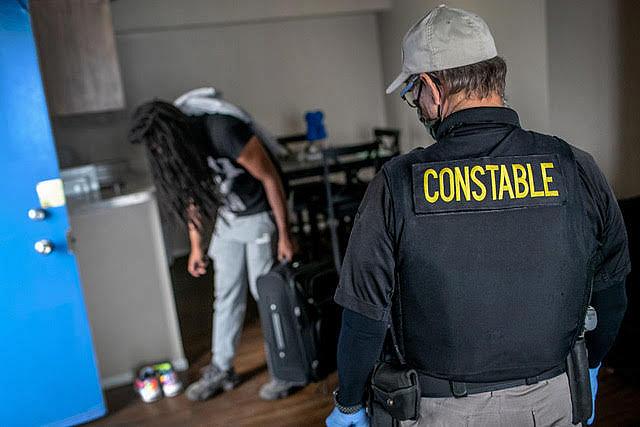

A Maricopa County constable evicts an apartment resident for nonpayment of rent in Phoenix, Arizona.

(Photo by John Moore/Getty Images)

Will millions of Americans who couldn’t pay rent because of the pandemic suddenly be thrown out of their homes?

It’s a question reporters have been trying to answer for months now. But a recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling adds fresh urgency to the story.

Late last week, the court overturned the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s ban on evictions in regions with high spread of COVID-19, which was set to expire Oct. 3. Journalists around the country have since sought to explain to their audiences the impact this will have on their communities, particularly since most of the funds for emergency rent relief have not been distributed.

As Subrina Hudson wrote in the Las Vegas Review-Journal, the justices’ decision is expected to have few repercussions in Nevada, as the state this year passed a law that “slows the eviction process if a tenant has a pending rental assistance application (and) allows landlords to apply for rental aid on behalf of their tenant.”

“We’re fortunate in Nevada … because we still have solid protections in place for tenants to avoid eviction,” Jim Berchtold, directing attorney of Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada’s Consumer Rights Project, told Hudson.

Hudson says her next line of reporting will focus on how the courts interpret the law.

“Nothing in the (Nevada) bill gives a time frame of when a tenant should have applied for rental assistance before receiving their eviction notice,” she said. “I've spoken with tenants who've had a pending rental assistance application for a month to as long as about three months and they're still getting evicted.”

A handful of other states — such as California, Illinois and New Jersey — already had eviction bans of their own and thus won’t be impacted by the Supreme Court’s ruling.

“The CDC moratorium had little effect in California,” Louis Hansen, housing reporter for The Mercury News in San Jose, told me. “The state moratorium was stronger than the federal protections, so they take legal precedence.”

But tenants in most states no longer have such legal safeguards.

As Nushrat Rahman reported in the Detroit Free Press, evictions for nonpayment of rent in Detroit were set to resume “immediately” following the ruling.

"It was heartbreaking, disappointing, devastating,” Tonya Myers Phillips, public policy adviser for Michigan Legal Services, told Rahman. “That means millions of tenants across the country, not just here in the Detroit area, are at risk of eviction. They, and their families, are at risk of being homeless.”

But Aaron Cox, a Michigan attorney who represents landlords, told Rahman that property owners ultimately just want to get reimbursed for back rent through the state’s COVID-19 emergency rental assistance program.

"It's not like landlords are going to just run out and try to throw people out of their properties for simple nonpayment of rent issues when (rent relief) funding is otherwise still available,” Cox said, according to Rahman. “The landlord's goal at the end of the day is to get that payment.”

Statewide, Rahman reported, only $152 million of the $622 million allocated to Michigan had been distributed as of last week. Across the country, only about 11% of the $46.5 billion dedicated to rent relief has been spent, according to data released by the U.S. Treasury Department on Aug. 25.

In Colorado, renters only have a few more days to seek protections, the Denver Post reported. A governor’s order, set to expire Saturday, delays evictions by 30 days for tenants who’ve applied for rental assistance.

“It’s been a race against the clock,” attorney Zach Neumann, of the Colorado Eviction Defense Project, told The Post’s Alex Burness. “And now that clock has struck midnight. We’re out of time.”

About 4.6 million American adults — including 43,000 in Colorado — report being somewhat or very likely to be evicted in the next two months, according to U.S. Census Bureau data.

Renters most at risk of eviction are most likely to live in neighborhoods with low COVID vaccination rates, increasing the risk for further spread of the coronavirus, researchers at the Eviction Lab at Princeton University found. Those tenants are disproportionately Black and Latino.

The Eviction Lab tracks the the number of evictions in six states and 31 cities since the start of the pandemic. Other good data sources for journalists reporting on housing and COVID-19 include the National Equity Atlas’ Rent Debt Dashboard, the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley, and the National Low Income Housing Coalition’s Treasury Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) Dashboard.

Hansen, of the Mercury News, said the state and some local governments have been transparent on how much rental assistance is going out. For instance, Santa Clara County, home to San Jose, has a dashboard that tracks distribution of the funds — $12.6 million has gone out so far, of more than $52 million that’s been requested.

So he’s pivoted to reporting on how communities are planning to get the money to hard-to-reach populations, whether that’s through state courts, church groups or other local nonprofits.

“Look for the choke points,” Hansen said. “As reporters, just find these pain points and how are your communities trying to solve them. Is it a language problem? Do you not have enough Vietnamese speakers to help families in the Vietnamese community fill out applications? Is it a reluctance from landlords: Are they skeptical and have they had bad experiences?”

Added Hansen, “There's been a lot of pain points in this process.”

**