Reporting on Health Collaborative demonstrates how media can help fix problems

Journalists have a knack for pointing out problems. They rarely explain how to fix these problems. The message to readers is: the world is a mess. You figure out how to make it better.

If I had to put a ratio to it, I would guess that the number of stories I have written where I pointed out something was wrong compared to the number of stories where I suggested how to do something right would be about 5 to 1.

There is a growing movement among reporters to remedy this, with Exhibit A being the fantastic Fixes column by David Bornstein and Tina Rosenberg.

We at the Reporting on Health Collaborative are doing our small part with the Just One Breath series about valley fever. For three months, we have been telling readers about the problems associated with the rising number of cases of the fungal disease. In each story, the reporters have looked for opportunities to explain how these problems might be fixed.

This weekend, Rachel Cook from the Bakersfield Californian, gathered up many of these ideas into an action plan. Here are four tips from her piece.

Mark the calendar. Sources often talk in vague terms about how long it will take to accomplish a goal. Try to pin them down and then do enough reporting so that you can write with authority about a timeline. Over the course of the project, the reporters spoke to enough sources and read enough of the relevant literature to write:

The Reporting on Health Collaborative asked patients, physicians, researchers and government officials to identify steps that could be taken now to change the course of the disease. Five key action areas emerged from those conversations with a rough timeline of targets for specific achievements:

• Improve how doctors identify and care for valley fever patients immediately through training.

• Implement a robust surveillance system to track the disease, especially in California, by 2014.

• Develop better tests for the disease by 2015.

• Bring to market modern treatments for valley fever by 2017.

• Raise enough money to finish the work of creating a vaccine, the silver bullet in the fight against valley fever, by 2022.

Think small and think big. Solutions don’t have to be earth shaking or history making. With valley fever, there is a lot of discussion about the promise of a vaccine, but it became apparent through our reporting that a vaccine was still at least a decade away and that significant hurdles remain for one to successfully prevent the disease from occurring. A much more realistic goal in the near term is simply to train physicians to spot and treat the disease. Cook wrote:

Perhaps the quickest way to put a dent in valley fever is by increasing doctors’ awareness of coccidioidomycosis so that they detect the potentially deadly disease earlier and get patients on the right course of treatment faster. Coccidioidomycosis may be mistaken for any number of other ailments, delaying treatment and prolonging suffering.

Hunt down successes. Most of the outlets involved in Just One Breath have a local focus, but for the series, they spent a lot of time reporting about Arizona. The state has taken valley fever more seriously than California, in part because the disease hits the largest population centers in Arizona while in California it is mostly confined to the Central Valley. If people in Los Angeles and San Francisco were suffering from valley fever at the rates they are in Bakersfield, you can bet the state would start adopting some of Arizona’s policies. Cook used Arizona at several points in her action plan piece to showcase a success:

With more money dedicated to valley fever, Arizona has been aggressively tracking valley fever cases for about five years, said Shoana Anderson, chief of the Arizona Department of Health Services’ Office of Infectious Disease Services. “The challenge is really understanding what the data is telling us,” she said.

When a doctor logs on to the state system and reports diagnosing a new case or a testing lab reports a positive result for the valley fever fungus, the state system receives an instantaneous report and incorporates it into its tracking, identifying clusters of cases by geography and time.

The system provides information about how long it took before patients went to a doctor about their symptoms, how long they’ve lived in Arizona and other information that helps improve communication with the public and public education, Anderson said. She said they’re trying to determine why people seek health care for valley fever and improve on it, so patients recognize symptoms and seek help sooner.

Be realistic. When you are trying to help a community find a solution to a problem, there can be a tendency to get caught up in the optimistic spirit and forget your oldest reporting tool: skepticism. Cook ended her piece by noting that none of the target dates at the beginning of her story will be hit if there’s not a robust community effort pushing for change. She wrote:

Valley fever’s history is cyclical. Enthusiastic people get a little money to make something happen, but then the money dries up, said Kirt Emery, Health Assessment and Epidemiology Program Manager for the Kern County Public Health Services Department. The efforts need the support of local governments, federal agencies, businesses and private foundations as well, he said.

“If we’re going to be successful we’ve got to come up with really more of a business model of acquiring funds,” Emery said.

Have your own ideas for making valley fever a disease for the history books? Send me a note at askantidote@gmail.com or via Twitter @wheisel.

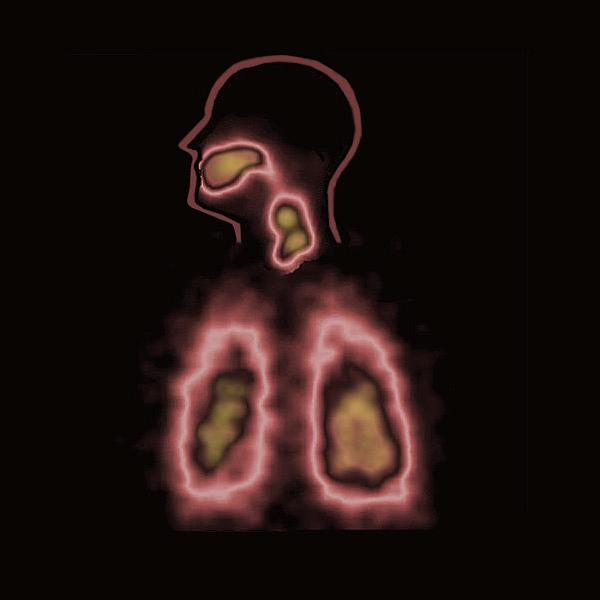

Photo credit: AJ Cann via Flickr