Reporting from Indian Country Requires Understanding Tribes' Diversity

Though I have often reported on traumatic events in Indian country, this series of three stories on Native youth suicide was particularly harrowing—perhaps because the trauma was so severe, so widespread and involved harm to children. It showed me how important it is to take care of yourself and your own psychological needs during such an ordeal. Get enough sleep, eat right and keep connected with friends and family. If you don’t, I learned, you become exhausted and depleted.

What I did:

In three stories that appeared in Native and non-Native publications (online and print), I reported that Native youngsters kill themselves at a rate least 3.5 times higher than other Americans. Tribes have declared states of emergency, and the federal government gave nearly half of a recent round of major suicide-prevention grants to tribal organizations. On some reservations, every family is touched by this crisis. The first story was an overview; the second focused on three tribes’ programs; and the third was a close-up of suicide-prevention camps in Alaska, where rates are highest.

My reporting took me to five reservations and Washington, D.C., and was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism, as well as by the California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowships. I did extensive document research and interviewed well over 100 experts, including tribal chairpersons and mental-health and child-welfare staffers; officials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and other agencies; officers of funding organizations and advocacy groups; scholars and creators of suicide-prevention curricula; and tribal members, young and old, who had survived their own or family members’ suicides.

I found great despair, but also vigorous, creative efforts to stem youth suicide. Some tribes have already seen inroads in their suicide rates, which, had they been left unchecked, imperiled the existence of their communities.

Because my work appeared in non-Native and Native outlets (nbcnews.com, 100Reporters.com, and indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com; the last also published it in its print magazine), I interpreted this phenomenon for readers who were living the story and those who were entirely unfamiliar with Indian issues. The articles were widely read in and out of Indian country—picked up by reservation newspapers and Native and non-Native news, law, and opinion blogs.

On nbcnews.com, the first story garnered about 103,000 page views and 3,000 shares/tweets (“it got around,” said its NBC editor). It was named an Aspen Institute Best Read of 2012, and Indian Country Today made it an Editor’s Pick. Groups, including the American Society for Suicide Prevention, posted it on their home pages. The second and third stories appeared in ICT only (print and online). The Nebraska Commission on Native American Affairs applied my information on protective-factors research to their teen-leadership programs. My work has been used and quoted as an expert source by other journalists writing on Native suicide.

Lessons other mainstream journalists can apply:

One of the most interesting things I can probably do for all of you is tell you about how to proceed and things to watch out for if you report Native stories. It is a very different world from the one most of us mainstream reporters inhabit. Here are ways to make Indian-country stories easier to put together and more accurate. Some of it may seem complex, but once you’ve been through a story or two, it’s obvious. In any case, you don’t have to be a legal scholar and explain masses of detailed information to your readers. You just have to tell your readers what's needed to understand your story:

• I hear a Victorian-sounding locution around these days: “The tribes” do this or that. It has an odd formality and distancing quality to it. It’s used when the writer means that some particular tribe or tribes, or even some particular Native individuals, do or espouse something. There is no uber-organization that causes various Native people or tribes to fall into line over policies or activities. Each one is a nation unto itself. Be specific.

• There are 566 federally recognized tribes. Each has its own culture, language, history and relationship with the federal government. That government-to-government relationship occurs in the context of treaties, executive orders, laws, court decisions and more. Anything you learn in doing a story on one tribe may not apply to another one, even to the tribe next door. If you’re headed for a reservation, find out what major documents apply. Then, when someone refers to the 1868 boundaries, or the 1805 fishing rights, you’ll know what they’re talking about and can ask what you need to know for your article. To many non-Native people, treaties and other such documents may seem like antiques—musty items consigned to the nation’s legal attic—but they are part of U.S. law and figure in negotiations and court cases every day.

• Because tribes are nations, they have all the activities of nations in realms ranging from economic development to cultural events and back again. Everyone is very busy, often on issues that are critical to the survival of the community. From preparing for a Supreme Court case to making sure children have warm clothes for winter, everyone wakes up on a reservation ready for action. Your article may be important to you, but the tribe and its members may be facing an immediate crisis, or more likely many of them, that you’re not aware of. Set your interviews up well ahead of time, and give yourself plenty of options. And be on the lookout for even more interesting stories that the one you set out to report.

• About half of tribal people live off their reservations, in cities around the country. These are referred to as urban-Indian communities; many have community and health centers, as well as enterprise zones, art centers, festivals and the like.

• This may be obvious to you, but surprisingly many may not realize that Native people are U.S. citizens, with the rights of all citizens. That said, they have a constant struggle to exercise those rights; voting is a particular problem, though it’s 50 years after those battles seemed largely settled for other population groups.

• If your story has anything to do with crime or misdeeds, know that jurisdiction is complicated in Indian country, having to do with who committed the alleged crime, who was the alleged victim, whether the crime was one of the “major crimes” over which the federal government has jurisdiction, and where the alleged crime occurred. CASA has a good explanation; see the chart on the third page of the article. As a result of this jurisdictional tangle, and the fact that the FBI declines to prosecute many cases referred to it, reservations have become crime magnets for white-on-Indian crime. The statistics are highly skewed; according to the DOJ, non-Native men are the perpetrators in more than 80 percent of rapes of Indian women; some women’s groups put the number at over 90 percent. See also Amnesty International’s “Maze of Injustice,” re: violence against women, since we learned in this document and the more recent VAWA debates that this means rape prosecutions rarely occur. For several years, people have been reporting that Native mothers bring their young daughters to health-care or women’s-advocacy organizations to prepare them for when, not if, they’ll be raped.

• You’ll note above that where a crime or any other event occurred can be important. Contrary to the popular notion that tribal land is held in common, there are several kinds of tribal and private ownership (white and Indian) on reservations, and different laws can apply on different parcels of land. If where something happened affects your story, ask someone who knows what they’re talking about (a tribal lawyer or official, for example) what kind of land is in question and what that means.

• More about adjudications; as reporters, we rely on adjudications and court documents for reliable backup. In surprisingly many situations, Native people do not have representation in court or only at a late stage in the proceedings, driving the disproportionate numbers of incarcerated Indians and making adjudications iffy sources. Before you make any pronouncements about the results of someone’s contact with the law, find additional sources.

• Talk to Indians, so their voices and always surprising points of view are part of your story. In the second decade of the 21st century, after all the attempts at assimilation, their cultures are still unique, so the way they experience and explain anything is as well. That is what makes Native stories so interesting; so much of your reporting will be unexpected. Women, especially older women, are extremely influential and well informed about internal and external issues on all reservations I’ve visited. Non-Native people—perhaps staffers at a nonprofit, or non-Indian tribal employees—are often quickest to respond to interview requests, and they may provide useful perspective; however, I have found they can also be stunningly mistaken about even the most basic facts.

• When seeking experts for comments, include the Native professionals in the field your story falls into—lawyers, doctors, professors, scholars, research scientists, educators, counselors and so on. They will have a distinctive point of view and be able to refer you to community people as well, giving you yet more sources.

• Before you consult a corporate expert (like those from Peabody Coal or TransCanada) on a tribal matter, know what they’re up to in Indian country. Then you’ll understand, for example, why they’re telling you sending an oil pipeline through a tribe’s only water source is just fine.

• Federal sources and experts have their own agendas. The Bureau of Indian Affairs and FBI may have an adversarial relationship with a tribe or tribal individuals in whatever matter you’re looking into—even, or especially, if they’re making cooperative noises. Critics of the agency believe the BIA often stands in the way of reservation residents starting businesses, building homes and so on, sometimes by discouraging people, and sometimes by withholding crucial information they need to move forward.

• Be conscious of longtime rivalries between environmental organizations and tribes over management of natural resources.

• Avoid taking photographs of broken-down trailers or messy housekeeping as a shorthand for poverty. And avoid the empty swing sets to show child-welfare problems. All of these have been done and done (and done). Find another way to convey complex positive and negative information—images that don’t allow the reader to objectify your subjects. I once asked a Native activist what the messy housekeeping pictures were all about, and he said, "They’re to show we can’t take care of ourselves."

• Is Indian country safe? Yes, though naturally you should take whatever precautions you usually take when you are reporting in any city or town in the US. This may also depend on what you are reporting. On or off a reservation, an article on meth labs poses more risks than one on organic gardens.

Editor's note: For another journalist's view on the challenges of covering Native American issues, read Victor Merina's essay for ReportingonHealth.

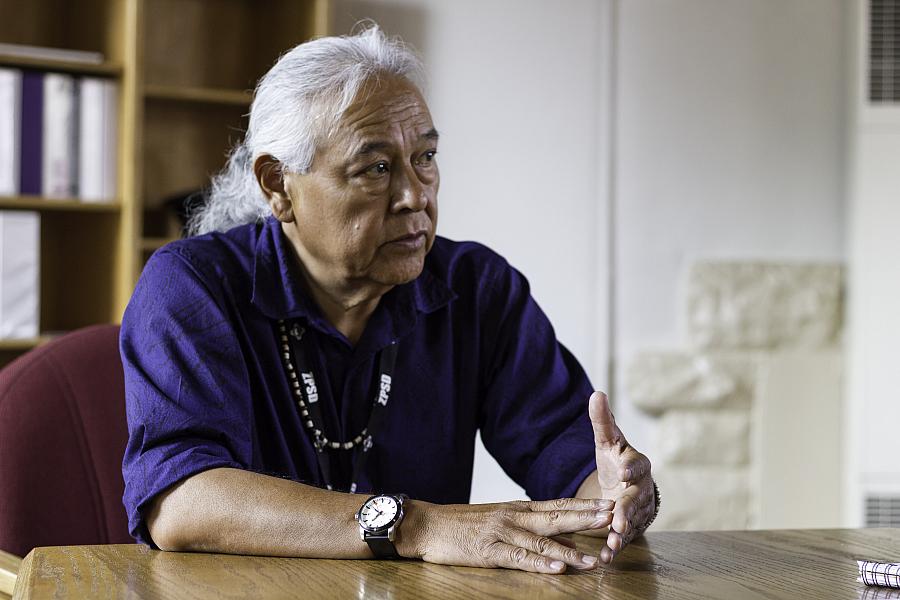

Photo Caption: Zuni Pueblo's superintendent of schools Hayes Lewis speaks about an influential suicide-prevention program he helped create at the pueblo.

Photo Credit: Joseph Zummo