Shaken baby: 'A false and flawed premise'?

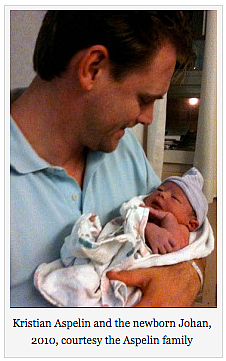

The shaken baby debate picked up in early February with a pair of important and complementary postings, a bold academic statement signed by 34 physicians, attorneys, and child-protection professionals with “deep concerns” about shaking theory in the courtroom, and a beautifully written examination of the Johan Aspelin case that illustrates why the experts are so concerned.

Published in the British journal Argument & Critique, the Open Letter on Shaken Baby in the Courts: A False and Flawed Premise argues that a diagnosis of shaking “risks blurring the line between diagnosis and verdict,” and that “SBS has never been proved as anything more than an hypothesis.” Citing the dearth of scientific research underlying the theory, the authors write:

Noticeably, the requirement for scientifically based evidence is far more rigorous in medical negligence cases than in the family or criminal courts where believing something to be true appears to have achieved sufficient evidential value to sway the determinations of the court.

The letter also notes that the justice system has tended to suppress arguments about shaken baby syndrome:

One of the consequences has been the vilification of experts prepared to advance competing theories and the suppression of sensible debate.

My favorite report about Dr. Squier’s GMC hearings, which opened in the fall and continue intermittently, is a legal-training company’s blog posting that features praise from readers for her intellectual honesty in the face of peer pressure. A general practitioner offered this striking parallel with an historical report to the GMC:

Surely the Met investigating a Dr who happens not to agree with the consensus — and holds an expert view — is a little like the tobacco companies (circa 1960s) reporting Sir Richard Doll to GMC for his novel theory that tobacco caused lung cancer.

In the U.S., meanwhile, an in-depth treatment of the Johan Aspelin case published last week on Medium by reporter Elizabeth Weil also reveals striking new facts, like the botching of Johan’s initial intubation at San Francisco General, which caused the complete collapse of one lung and serious damage to the other. Johan also received several times the recommended dosages of two different sedatives, which, Weil writes, “left him essentially paralyzed and unable to communicate distress as air was pumped into his compromised lungs.” The article notes:

Nowhere in the police investigation transcripts does it suggest that doctors considered Johan had a brain injury and retinal hemorrhaging due to low blood-oxygen levels and high carbon dioxide pressure, problems that may result from faulty intubation.

Johan’s mother Jennie Aspelin learned about the error and resulting crisis only because she’d contacted the organ-donation agency to find out why there had been no recipient reported for Johan’s lungs, as there had been for his other organs. Even then she received only the oblique message that it was “a matter of function,” enough to send her on a focused search for the full medical records.

In November of 2010, Johan’s father Kristian Aspelin told emergency responders that he had fallen in the kitchen while holding 3-month-old Johan, but child-abuse expert Dr. Chris Stewart rejected that explanation and told police that the boy had been violently shaken to death.

In December of 2012, the county dropped murder charges against Kristian, after defense attorney Stuart Hanlon turned over a collection of exonerating reports from outside experts as well as a carefully assembled medical time line that included the hospital’s mistakes. By that time, the family had lived apart for two years, after the death of their baby, when they needed each other more than ever. They’d sold their house and taken on a staggering debt to cover legal bills, and they’re not slated for any compensation from the state.

But the people who train child abuse physicians continue to teach that children seldom if ever suffer serious injury in short falls, and that only abuse causes severe retinal hemorrhages. In a January, 2015 lecture titled “Is There a ‘Shaken Baby Syndrome’?,” for example, which earns the medical viewer one continuing education credit, child abuse pediatrician Dr. Mark Feingold reported that hypoxia does not cause “macroscopic subdurals” and that children do not suffer serious injury in short falls:

A lot of our opponents say, “Well, the child died. That’s too bad. But it was a short fall, just like Mom said. He fell from Mom’s arms.” The evidence shows that children who fall more than 20 feet can die, but children who fall less than 3 feet almost never die, and when they do, it’s a different kind of accident. It’s a playground accident. It’s an older child. They die of a large subdural that causes lots of pressure. And the RH if present are not the kind we see in abuse cases (emphasis added). But nonetheless, different versions of “I was carrying the baby and I tripped and fell” are often offered.

Slipping and falling with the baby is the explanation Kristian Aspelin offered, like countless parents and caretakers before him and countless more to come, while pediatricians are being trained to reject that story, and to dismiss the hypoxia that frequently accompanies head injury as a source of compounding symptoms.

Subdural hematoma and retinal hemorrhages—that is, bleeding between the outer two layers of the brain lining and bleeding in the backs of the eyes—are two of the defining features of shaken baby syndrome, now known as abusive head trauma. The retinal hemorrhages in Johan’s eyes were widespread and multi-layered, the kind that child abuse pediatricians insist do not result from short falls or lack of oxygen to the brain. So were the hemorrhages in the retinas of the toddler in the care of René Bailey, who said the little girl had fallen off a chair—Bailey’s murder conviction was vacated in December. Doctors also pointed to extensive retinal hemorrhages when diagnosing shaking injuries in the cases of exonerated babysitters Jennifer Del Prete and Audrey Edmunds and exonerated fatherDrayton Witt, and in an exasperating case local to me in which paramedics pulled a rubber band from the child’s throat during resuscitation and the only physical evidence of abuse was the triad of subdural hematoma, retinal hemorrhages, and brain swelling. It seems to me that the world now offers quite a few examples of extensive retinal hemorrhages from plausible, non-abusive accidents and medical conditions.

I don’t know how we will move forward, but I welcome the growing chorus of voices in the journals, in the press, and in the courtroom, who demonstrate through their work and their testimony that the Open Letter on Shaken Baby is representing the situation correctly in its message to the courts:

In short, we would inform members of the judiciary and legal profession in those countries which utilise the SBS construct, that it does not have the undivided support of the relevant professional community, an essential consideration in the assessment of expert testimony.

The letter was edited by Argument & Critique’s managing editor Dr. Lynne Wrennall, whose doctorate is for work in child welfare, from a draft prepared by solicitor Bill Bache and veteran child social worker Charles Pragnell. The signers include 16 physicians, a handful of scientists, and a variety of social work professionals, from both academia and the field.

For the observations of Phil Locke at the Wrongful Convictions Blog, see hisposting about the Open Letter.

The film company Mighty Myt is making a film about Johan Aspelin’s case, In a Moment: The Johan Aspelin Story.

copyright 2015, Sue Luttner

If you are not familiar with the debate about shaken baby syndrome, please see the home page of Sue Luttner's web site.