The stigma question: Interviewing "Real Faces" Behind Mental Illness

When I first pitched a series of stories exploring access to mental health care in the wake of state budget cuts (also available here), I expected to encounter some difficulty finding subjects.

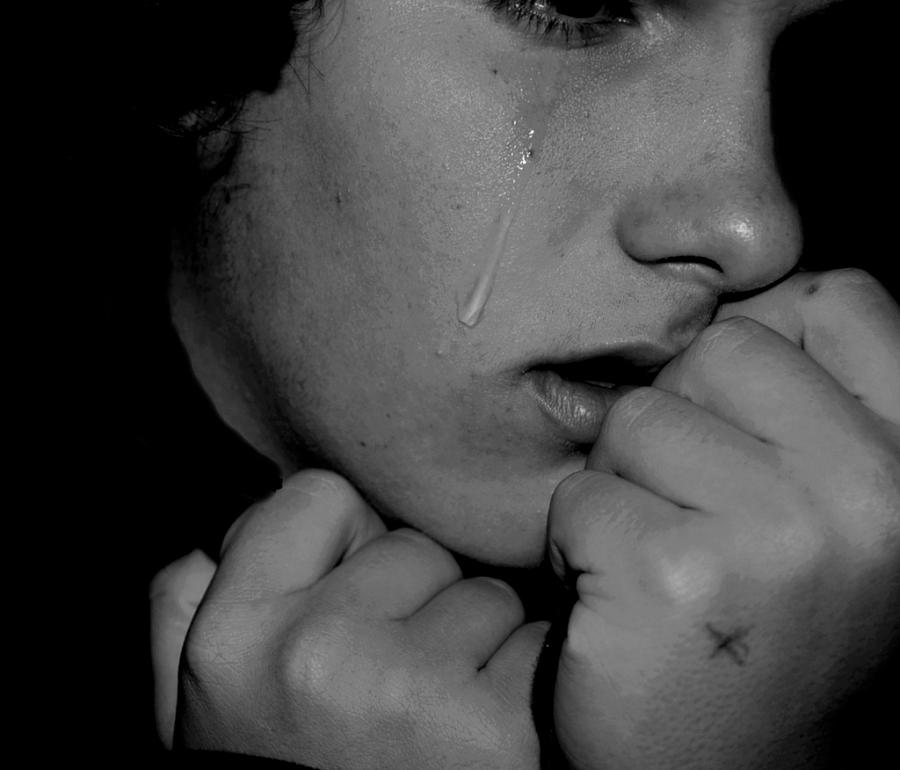

Mental illness remains among the most stigmatized of health problems in our society. In pitching the project to the Rosalynn Carter Fellowships for Mental Health Journalism, and later, to the USC/Annenberg California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowships, I highlighted such stigma as both a major obstacle to capturing the human face of this story and an important reason to tell it

I was right – but not necessarily in the way I expected.

During one of my first interviews, the woman I spoke with was very candid about the multiple voices in her head, and about how hard it had been to get services. She was a perfect subject, and said incredibly quotable things: "I'm stuck out in the middle of nowhere and it's horrifying," she told me, as she slipped deeper and deeper into her illness. But she was only comfortable being identified by her middle and last names – Marie Lopez. Some day, she said, she hoped to be strong enough to confront the stigma surrounding her illness. But she wasn't ready yet.

I certainly understood her perspective. After all, once your name is in the paper these days, it is also online. It's hard to erase that trail with prospective employers or acquaintances that might be scared of an illness they don't understand.

I braced myself for more of the same, even talking with my editor about what we would do if no one wanted to let us use their names.

The morning after that first interview, I had several more conversations lined up with prospective subjects, thanks to help from Joyce Plis, the deeply committed executive director of the local chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. I spent more than an hour with each person, and in the months to come, met with many others.

One was a real estate agent who told me she'd landed in jail after crippling depression led her to leave a suicidal voicemail on her mother's message machine. That message, she said, had seemed threatening to her mother, and she was given a short jail sentence. After getting out of jail, she told me, she couldn't find any county services to help her get the necessary psychiatric medication.

And, certainly, I could use her name.

Another woman told me about her struggles to be seen by the local inpatient psychiatric emergency facility, Doctors Behavioral Health Center. Despite being homicidal and suicidal, she told me, they wouldn't let her in on numerous occasions.

And, yes, by all means, use her name.

A third woman had been uninsured since her bipolar disorder left her unable to work six years earlier. She described managing her own medications because she couldn't afford a psychiatrist. She told me she'd been reduced to tears on several occasions after it seemed that every door was slamming shut on her.

"You just sit there and say to yourself, ‘Where do I go now?'" this woman, Susan de Souza, said. "‘What do I do? There's nothing left for me.' You feel really hopeless and helpless. You're trying to do what's best for yourself. You're trying to stay healthy. And you have people saying to you, you know, ‘I'm really sorry but there's nothing I can do.'"

Please name her, de Souza said. She was tired of the looks that would flash across people's faces when she explained her illness. She was tired of the stigma. She wanted to be an agent of change. She wanted to give mental illness a voice.

I was humbled, over and over again, by the courage of these and other subjects. Stigma around mental illness remains very real, after all. And no one understands that more than those who suffer its direct impacts.

That doesn't mean such stigma wasn't a problem in our reporting, though. It just came from a different source than I'd imagined: mental health workers.

There are all kinds of confidentiality issues involved in reporting on health care these days. In many ways, those reporting obstacles provide important protections for patients. But some clinics, and many government agencies and hospital chains, put inflexible rules in place that make it difficult for reporters to give a human face to a story, even when the patients themselves are happy to participate.

As a health reporter, I'm used to finding ways to work around these obstacles. But the people who tried to prevent us from photographing and naming subjects with mental illness weren't just in clinics or hospitals. They were anonymous "concerned" mental health workers. Instead of talking through their worries with us, they registered their concerns with the folks at NAMI and with some of our main subjects.

They worried that, by featuring the stories of people with mental illness, we would expose those individuals to stigma. And they suggested that people with mental illness were not in the position to understand the ramifications of their participation – despite the fact that these were intelligent, competent adults, none of whom were pressured to participate.

Rather than see our story as a vehicle to potentially mitigate stigma, they assumed it could only serve to make such stigma worse.

On a few occasions, these would-be protectors actively tried to intervene to stop my colleague Lauren Whaley from taking photographs of people with mental illness, or to convince one of my main subjects to pull out of the story at the last minute. Because they didn't speak directly with us, unfortunately, we couldn't tell them about our story and its objectives. In most cases, we had no idea who these critics were. As frustrated as I was by the seeming close-mindedness of some of these anonymous naysayers, I understood that most were acting in what they considered to be their clients' best interests. (A few, from what I gathered, were concerned that the story might cause them legal problems or the loss of grant money.)

Luckily, in the end, there were enough people who understood and supported our story that we were able to go ahead as planned.

I was humbled and grateful for the courage of these individuals and their families.

Once it was published, one of the most remarked upon features of the package ended up being Lauren's gallery of simple black and white portraits of people in the community with mental illnesses, displayed alongside nothing more than their names and ages.

Susan de Souza, who was among those featured, emailed me the first day the story ran.

"It was nice to see "real" faces behind mental illness," she wrote. "Thank you so much for allowing me to be a part of it. I feel very honored."