Veteran journalist: Be skeptical of nonprofits’ claims, finances

Do-gooders don’t always do good. Not all nonprofits are non-profit.

These well-known realities pose a few challenges (and opportunities) for reporters. After all, no self-respecting journalist wants to swallow wholesale the exaggerated or downright false claims some nonprofits occasionally make in justifying their raison d'être. And in today’s newsrooms, most reporters don’t have the time to fully evaluate such claims.

“The biggest mistakes I’ve made as a journalist have been when I’ve been naïve and didn’t know what I didn’t know, and I just left stuff out,” said Patrick Boyle, a journalist with over three decades of newspaper and magazine experience who now works as communications director for a Washington, D.C. nonprofit.

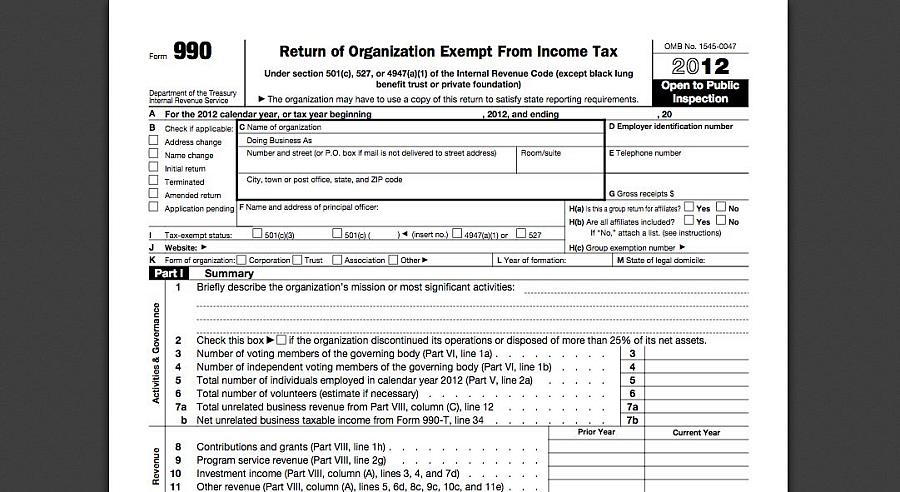

But how then does a reporter go about doing proper due diligence in reporting on nonprofits? Boyle, speaking to the 2013 California Endowment Health Journalism Fellows on Thursday, strongly urged reporters to begin by tracking down a nonprofit’s IRS Form 990 filing, and to do so even if you don’t suspect shady or inefficient practices.

“If a nonprofit is going to be a regular part of your coverage, at some point you should look at their 990,” Boyle said.

Taking at look at such filings can prompt new questions or refine the scope of your reporting.

“Knowledge is power,” Boyle said. “I just want to know what I’m looking at … It may make it into my story and it may not … It also makes my reporting more precise. Many times I’ve gotten into a 990 not knowing what I want to know, and I find things in there, because without the 990 I wouldn’t have known what to ask about.”

The website GuideStar.org offers one easy place to find many such filings, but you may need to contact the nonprofit directly to get the most recent forms. Nonprofits are required by law to provide 990s to anyone who requests them, so don’t bother explaining why you want them, Boyle advises.

When you get the form, start by taking a look at the summary of their most recent activities.

“You want to judge an organization by the organization’s own words,” Boyle said. The 990 will also reveal how much a nonprofit is spending to raise the money they’re spending. The results can be surprising. Boyle, pointing to a nonprofit’s recent filing that indicated they spent $2.1 million on contract fundraisers to raise $4.7 million, said, “These guys were spending almost all of their money to raise their money to spend their money.”

Here are a few other things to look for as you peruse the filing:

- Look at how much money has been raised over multiple years, and then compare that to how much they’re actually spending on their core mission.

- Check to see if the nonprofit is running a deficit. If you find one, especially one stretching back several years, ask the organization to explain.

- Look at the reported compensation of their highest paid employees. How does their pay compare to similar nonprofits or that of leading organizations in the field? (Be wary of nonprofits that try to keep their payroll off the 990 by using a payroll company to pay salaries -- that is illegal, according to the IRS.)

- Look for unexpected connections by doing some online research. Do any of the companies providing services to the nonprofit share addresses or other identifying marks with any of the nonprofit staff?

- Use common sense: A scuba diving nonprofit based in Nashville, Tenn., might strike you as geographically strange and worth looking into further.

There are of course other ways of checking-up on nonprofits aside from 990 forms. Boyle advises visiting the organization’s website and looking at its mission statement and what the kind of work the group claims to be doing.

“It’s amazing how often you’ll find out, even in their own brochures that are printed, the information isn’t true,” Boyle said. “I don’t think most of them are lying per se, flat out. I think they’re just really sloppy and they like to take credit for things they’ve thought about or are planning -- they get a little ahead of the game.”

It’s up to the reporter not to take such claims at face value, and a little phone work can go a long way.

It’s also worth asking how the organization evaluates the work it does. Boyle pointed to a Washington, D.C. nonprofit whose mission entailed serving the children of incarcerated parents. When Boyle asked the nonprofit’s CEO how they knew the kids’ parents were incarcerated, he said his team had gone into classrooms and asked for a show of hands of those who knew someone who is incarcerated -- this in southeastern D.C. They’d never bothered to verify the parents’ actual status.

That kind of sloppiness can raise some broader questions worth thinking about: How does the nonprofit you’re looking at know whether they’re reaching their target demographic? And what metrics are they using to define success when they do?

Starting with the 990 can give you a much-needed tool and put you on a path toward asking more informed, probing questions of organizations prone to making big claims.