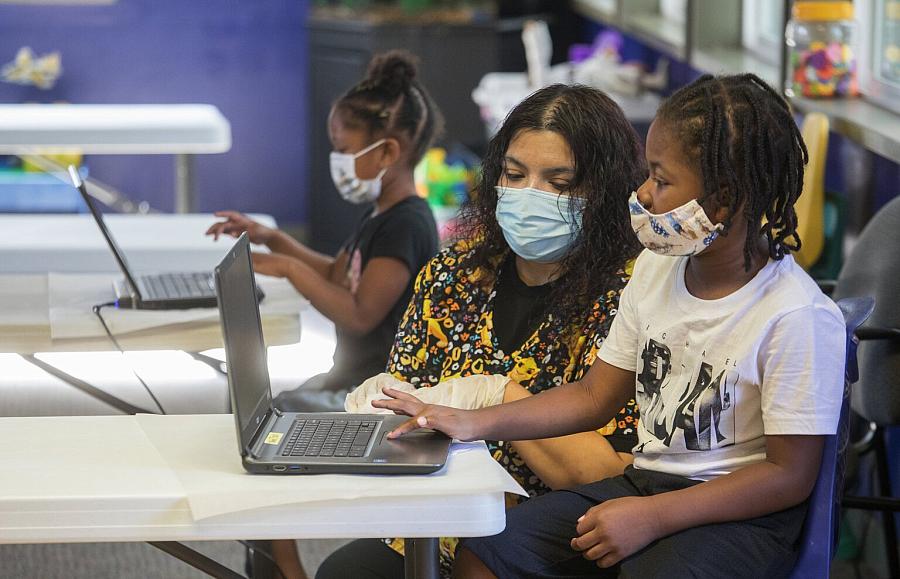

When the world went remote, communities on the wrong side of the digital divide got shut out

The pandemic sent students online in Seattle, but many in remote parts of Washington lack access to the Internet or reliable cell service.

(Steve Ringman/The Seattle Times)

Schools on a tribal reservation in Washington state were closed for in-person learning, as they were most places during the COVID-19 pandemic. Challenges abounded everywhere, but on this reservation they were fundamental: How could students connect to school when they lacked internet and even reliable cell service?

This sent one mother driving her three school-age children across the expansive reservation, chasing cell reception.

While in the high-tech metropolis of Seattle, many have been working by Zoom, ordering Amazon grocery deliveries and binging on Netflix, the digital divide has left the reservation’s population shut out of much of what passes these days for normal life.

The reservation lies in a remote area, with some of Washington’s highest poverty and unemployment rates. Laying the cable that allows for broadband access is not a money-making proposition for internet service providers. In the few places where there is access, many families say they can’t afford it.

As a result, 80% to 90% of the reservation’s residents lack a high-speed internet connection. Cell reception dead zones are abundant.

It’s a similar situation on other tribal and rural lands throughout Washington, one cast into high relief by the pandemic. What happens when much of the world goes remote and you live in a place that can’t? I will explore this question as a fellow participating in the 2021 National Fellowship.

I will talk to families, health care providers, teachers and others to learn about how the digital divide has affected various aspects of life during the pandemic, and what it means for the future as they try to recover lost ground and join a continuing online revolution.

I have already gotten a glimpse of the story.

I initially called a tribal leader wanting to talk for a story I was working on about delayed grieving due to the pandemic. The conversation quickly veered into one about the digital divide as he explained what a huge problem it has been.

“We had to really work with the schools to find ways of having curriculum hand-delivered, as well as meals,” he told me. Many of his reservation’s students come from poor families that count on the food. Some are the children of immigrants, living on or near the reservation while working on surrounding farms and orchards.

A significant number got so far behind academically they were told they might be held back a year. With some students, schools lost complete contact.

Although Native Americans have a higher rate of chronic disease than any other ethnic group in the U.S., telemedicine was difficult to impossible. So was telework, a problem for those that stayed home because of their vulnerability to COVID-19.

Communication became even more of a crisis when some of the worst, fastest-moving wildfires ever to hit Washington roared across one reservation last summer. People didn’t understand the speed at which the fires could arrive at their doorstep, and the lack of internet access made it harder to get the word out.

On another reservation, spotty internet service has created problems for mental health and addiction services. Unable to stay connected with providers and support groups, some people relapsed.

Students on yet another reservation started going to the courthouse at the beginning of the pandemic to do their work. The building is one of the few places with reliable cell service.

An internet service provider laid cable for broadband in the area but skipped over the tribal land and headed for the biggest nearby city. “It basically outlines the reservation,” a lobbyist for the tribe told me.

It’s not just tribal communities that have this problem. In Eastern Washington, rural kids and their families searched out buses turned into Wi-Fi hotspots and parked at strategic locations. One school district superintendent stood in a wheat field to talk about digital inequities for a video shown to state legislators.

As part of COVID-19 recovery packages, the state and federal government have now promised large amounts of funding to expand broadband access. While waiting for grant criteria and guidelines — ironically, some information is coming to digitally challenged areas via webinars — several tribes are proceeding with plans to become internet providers themselves.

So there is some relief on the horizon, but by no means is the problem solved, and I plan to look at the opportunities and the challenges.

I’m excited about jumping in further and sharing ideas with all the Annenberg fellows.