Why it’s way too soon to be talking about vaccine passports

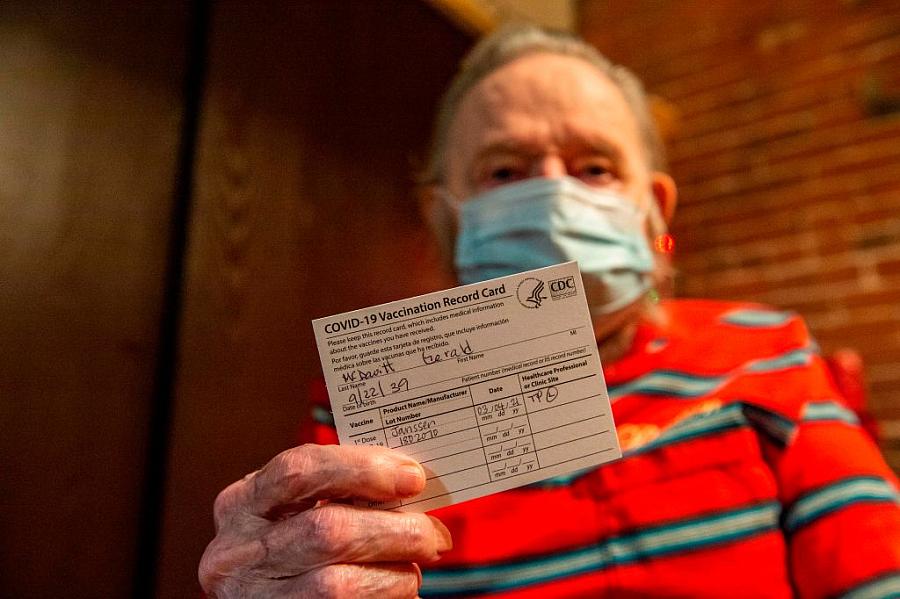

Gerald McDavitt, 81, a Veteran of the United States Army Corps of Engineers, holds his CDC vaccine card after being inoculated (Photo by JOSEPH PREZIOSO/AFP via Getty Images)

Much has been said lately about vaccine passports, which can show that a person has been vaccinated, with an eye toward speeding up the country’s return to normalcy. With some colleges, sports teams, and other organizations considering requiring proof of vaccination for entrance, vaccine verification may indeed be in our near future. While proponents cite public health and economic vitality as their main motivations, opponents argue that these passports can be an invasion of privacy and an overreach into the lives of civilians. Center for Health Journalism Community Editor Chinyere Amobi caught up recently with Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of American Public Health Association, on why he opposes the introduction of vaccine passports. Their conversation has been edited for clarity and conciseness.

Q. You’ve described the vaccine passport concept as a “slippery slope” that could politicize the vaccine rollout. Could you expand on that?

A. At our current state of vaccination, it’s way too soon to be using vaccine passports to document anything.

People of color, low-income individuals, and immigrants are having a much more difficult time getting vaccinated — even when they want to be vaccinated. Vaccine supply is dramatically increasing so theoretically that shouldn’t be as big an issue two to three months from now. But today, it’s a big issue.

And there are many people who may well misuse these passports. Health insurance companies can charge you more for not being vaccinated because of your risk. Employers can decide not to employ you because you’re not vaccinated. It can be used to deny you all kinds of things.

Q. Proponents in favor of making COVID-19 vaccination mandatory point out that we already need vaccinations to travel to different countries. How would this be any different?

A. There’s a national and international framework for certain kinds of infection control procedures and vaccinations. That hasn’t happened yet for COVID-19.

Remember when we were having states tell people from other states they couldn’t enter without quarantining? That’s another opportunity to misuse something like vaccine passports. Are we going to have states not allow certain people to come into their state because they’re not vaccinated? Is that likely to happen? I hope not. But I wouldn’t have thought we would have done those interstate quarantines and rules before the pandemic, and yet it happened.

Q. How might we might make vaccine verification more equitable, to ensure safety in public spaces? What’s the alternative to vaccine passports?

A. Achieve herd immunity. Which is how we do it with every other infectious disease that we have. We don’t stop people at the border because they’re not immunized against the flu. Now flu is not as serious a disease as COVID-19, but measles is significant, and we don’t do it for measles. We don’t do it for pertussis. We don’t do it for polio. These are all vaccine preventable diseases. But we believe we’ve achieved substantial community immunity from those diseases. And we have a very well-developed vaccination program. So we have a confidence that even if an outbreak occurred, we could contain it.

We don’t have that yet with COVID-19, but we’re still early on. We’ve been dealing with this disease for a little over a year, and we’ve only been vaccinating broadly for four to five months. Maybe some time in the future something like a vaccine verification might have some value, but I think we ought to be clear on what the value is.

Q. Some say the pushback against vaccine passports echoes the resistance to wearing masks. How is this different?

A. We’ll eventually have the parameters around when you need to show proof of your vaccination, and it’ll be ok. But if we do it too soon, it’ll become politicized, and it’s becoming politicized. So, you’ll have controversy when it doesn’t even do what we want it to do — that is, prove that you’re safe from infection.

Half the eligible public today has had their first shot and that’s wonderful, but here’s another thing: do you not let your kids go out with you? They could be infected, and they could be infectious. So, the family goes out to dinner with their vaccine cards and you’re not carding the kids, and you’ve not vaccinated the kids?

And what do you do if you have a medical condition that prohibits you from being able to be vaccinated? Do you not go out to eat? Do you have another card to show that you have a medical condition that prevents you from being vaccinated? As a nation, we haven’t thought through all these problems.

Q. How do you think journalists should cover this topic?

A. First of all, don’t demonize the concept. The concept of vaccine passports is essentially documenting your vaccination. Tell the story of what they’re really good for. Maybe talk about the history of them and how they are useful: They’re really good medical records to document that you’re vaccinated, for medical purposes. When you do international travel, or are in conditions where you need to document your vaccination status, they have a place.

Realize that folks like me who are skeptical may have a different mindset when we achieve herd immunity.

Q. Any final thoughts?

A. Let me add one other issue here. What are we going to do when we have to get booster shots? Let’s assume a future where we have enough change in the virus or the virus’ durability that we know that we have to get annual shots. Do you then need to get an updated renewal of your shot record? Does that mean you have to do it annually? Your passport’s good for a long period of time, as is your driver’s license. You’d be updating your shot card much more frequently than any other public document that we have, if we have to get a shot annually. We need to work through those kinds of things.

Every single year kids go back to school and we have to have major immunization clinics to update records. Some portion of those kids have had their shots with no documentation, which is a logistical nightmare. With vaccine passports, you’re talking about 330 million people at some point, with varying degrees of health coverage. We need to think this through.