In a world of scarce providers, what’s stopping telehealth?

Last week, a group of panelists spoke at the Rural Health Journalism Workshop in Portland, Oregon, about an issue long familiar to rural America: a need for health care and the lack of physicians to provide that care.

The concern is part of a growing anxiety about physician shortages across the nation. Under the Affordable Care Act, an estimated 14 million individuals have gained coverage through either the health insurance exchanges or Medicaid. The numbers beg the question: Who will take care of all these patients?

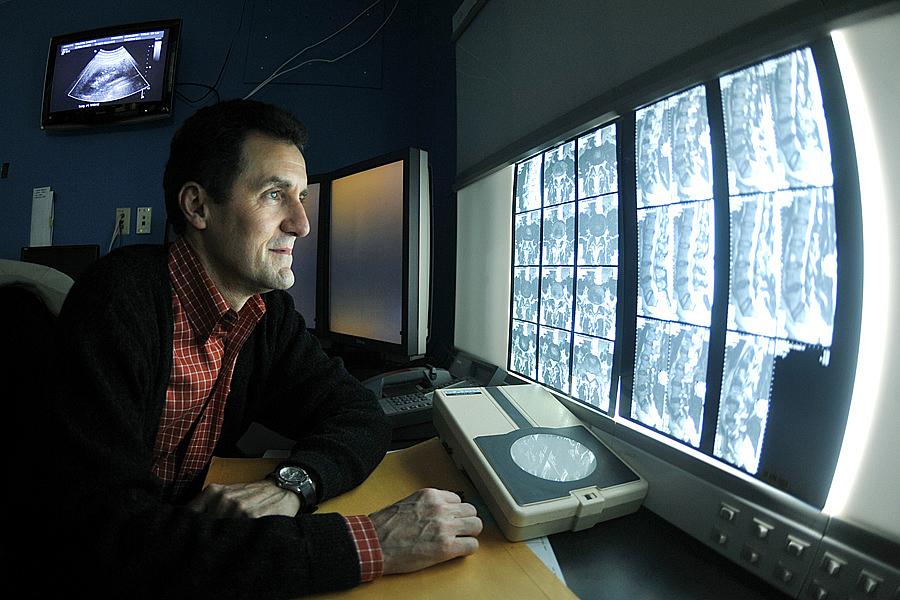

One of the potential solutions is telehealth, or the use of telecommunications technologies to diagnose, treat, and monitor patients remotely and, proponents say, efficiently. Patients in rural and underserved areas could see a far-away physician despite a local shortage. The elderly and those with chronic conditions could be monitored in their homes. Even patients with access to providers in their neighborhood could benefit from saved travel and wait time.

But despite its promise, telehealth hasn’t transformed health care the way proponents hoped it would. One of the main challenges, advocates say, is that policymakers have been slow to put forth clear, national guidelines and regulations around the practice. Currently, each state has its own set of telehealth policies – some more comprehensive than others – leaving providers to figure out whether they can practice over state lines or if they’ll be reimbursed for their work.

The absence of a national regulatory framework may have more to do with the political climate than telehealth itself. “We’re caught in [the] bigger picture of congressional politics,” said Mario Gutierrez, executive director for the Center for Connected Health Policy, a nonpartisan think tank devoted to telehealth. Any effort that adds to health reform is unlikely to pass right now, Gutierrez added.

One such effort is the Telehealth Modernization Act, introduced by Reps. Doris Matsui (D-Calif.) and Bill Johnson (R-Ohio) in the House in December 2013. The bill would clear up the patchwork of state rules and regulations covering telehealth. However, GovTrack.us has given the legislation a 1 percent chance of becoming law.

“The sense I get from the various leaders in Congress that are taking up the issue of telehealth is that they are using [telehealth bills] as a platform to elevate issues and also to educate,” Gutierrez said.

Even if the Telehealth Modernization Act were to pass, huge challenges remain in delivering care using such a system. The bill is based on legislation that was previously passed in California – legislation for which Gutierrez had advocated, and legislation that has yet to make a significant impact.

“We thought, ‘We’re off and running here,’” said Gutierrez, referring to California’s Telehealth Advancement Act of 2011. However, two and a half years after the bill was enacted, little progress has been made in implementing the law.

Some of the challenges include linking electronic medical records and telehealth diagnostic information. Software systems would need to be able to communicate with one another.

Telehealth also faces a lack of commitment from insurers, providers, and patients to change old infrastructures and habits, according to Gutierrez. “What we discovered is that this is a team sport,” he said. “It’s not enough to get a law passed. It’s not enough to get an insurance company to cover it. It’s not enough for providers to agree to use it.”

There’s still broad resistance to telehealth from doctors used to traditional practice. In a popular 2011 TED Talk, Dr. Abraham Verghese warns against the loss of the physical exam: “We’re losing a ritual that I believe is transformative, transcendent, and is at the heart of the patient-physician relationship.”

Some physicians are concerned that quality of care is compromised when doctors don’t use touch to assess physical conditions. Others worry about the security of patient information when using programs like Skype. Still others are afraid that patients may abuse the system by seeking out physicians for controlled substances.

Despite the slow pace, telehealth advocates are pushing on. On June 9, just days after the Senate confirmed her as the new secretary of Health and Human Services, Sylvia Burwell received two letters from the American Telemedicine Association and the Alliance for Connected Care. Both urged the new secretary to ease a variety of rules restricting the use of telehealth under Medicare.

Two days later, the American Medical Association endorsed the use of telemedicine as a way of improving access and quality of care while reducing spending. The AMA also set forth new guidelines around telehealth practices and reimbursement. (Not everyone thinks the guidelines make sense.)

Meanwhile, clinics in rural areas are already experimenting with telehealth, especially for mental health and dermatology. Insurance companies such as Kaiser, Blue Shield of California, and WellPoint are covering telehealth care.

Others may soon follow. Information and analytics company HIS Technology predicts that telehealth patient numbers will increase from less than 350,000 in 2013 to 7 million in 2018. Revenue is projected to follow suit, rising from $440.6 million to $4.5 billion in the same five-year span.

Photo by Offutt Air Force Base via Flickr.