Your assumptions about poor kids’ diets are, like mine, probably wrong

One could be forgiven for assuming poorer families lean more heavily on fast food to get through meal times. Fast food is cheap and, well, fast. And time and money are perpetually scarce in cash-strapped households.

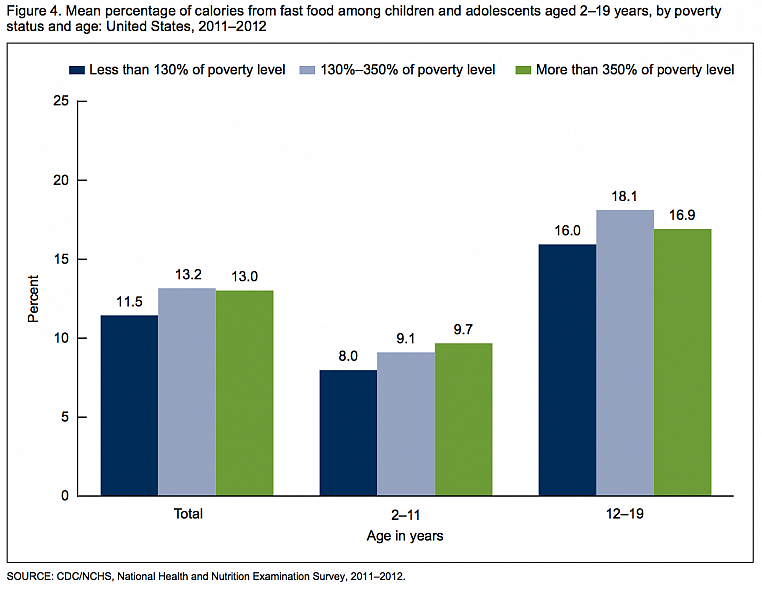

Perhaps the most efficient way of overturning that logic is by taking a look at this bar graph that the CDC released last week:

You’ll notice that in both age brackets — younger kids and adolescents — the children from the poorest households consume the fewest calories from fast food, 8 and 16 percent of their diets, respectively. Even so, these differences are too small to be considered significant:

“There were no differences by poverty status among either younger children (aged 2-11) or adolescents (aged 12-19),” the CDC report points out, drawing on data from the 2011-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Nor did being overweight or obese make much of a difference. “There was no significant difference by weight status for children aged 2-11 or for adolescents aged 12-19,” the report finds.

But if poverty level or weight didn’t make a significant difference in fast food consumption, what did? Age, for one. The percentage of calories consumed via fast food was twice as large for teens as it was their younger siblings. Race played a role as well, with Asian children consuming less fast food than other groups. (The CDC report suggests this is because more Asian kids were foreign-born during this period, and they hadn’t acculturated to the American diet yet.)

The data seem to stand as a corrective to the idea that since poor children are more likely to live in “food deserts” overrun by fast food outlets, they’re fed disproportionately by the drive-through lane. Such concerns are part of what led Los Angeles to approve a 2008 ban on new fast-food restaurants in South L.A., where poverty and obesity coexist at much higher rates than elsewhere.

But since then, new research has challenged the idea that one’s nearby food options and dietary habits are inextricably linked. In Los Angeles, the ban hasn’t had the effect proponents hoped for — or not yet at least. A report released in March found “that from 2007 to 2012, the percentage of people who were overweight or obese increased everywhere in L.A., but the increase was significantly greater in areas covered by the fast-food ordinance, including Baldwin Hills and Leimert Park,” as Soumya Karlamangla reported in the Los Angeles Times.

But just because the CDC’s latest data suggest that poor kids are eating no more fast food than their more affluent peers, that doesn’t mean they’re eating equally well. A recent review of 25 studies published over the past 10 years found that participants in the federal food stamp program consumed about the same number of calories as those with higher-incomes, but they were eating fewer fruits, vegetables, whole grains — and more added sugars.

“One of the major findings is we didn't find any difference in calorie intake,” the study’s lead author, Tatiana Andreyeva, told NPR’s The Salt. “The bad news is that the quality of diet is lower.”

In other words, just because poverty doesn’t correlate with kids’ fast food consumption doesn’t mean low-income families are necessarily getting their calories from nutritious food. There’s still plenty of room for programs that help low-income families buy and cook healthier fare. Given the health risks that attend poor diet, these are programs that can potentially lower health costs and pay dividends over a lifetime.

[Photo by USDA via Flickr.]