A battle for justice, in Denver’s ‘last frontier’

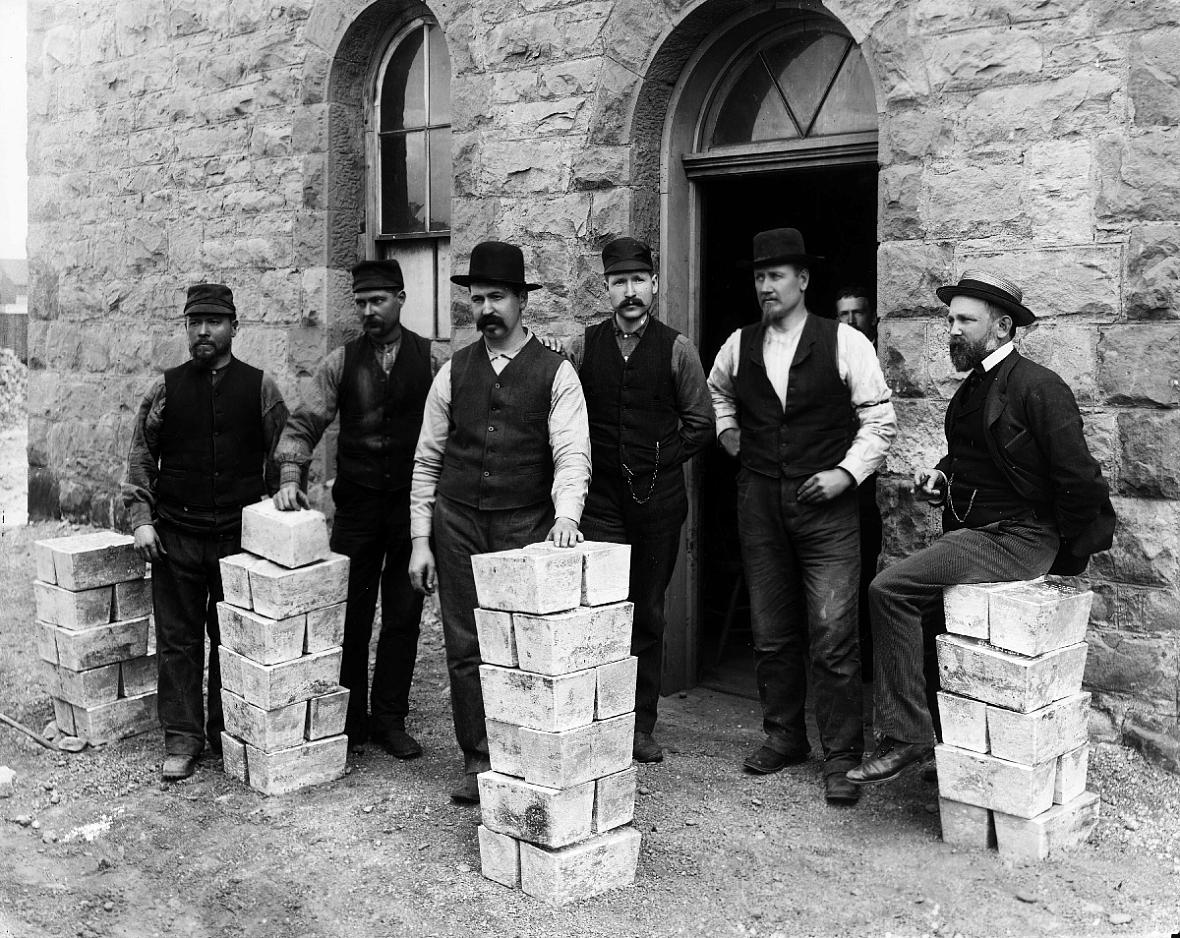

The Globeville area of Denver once attracted immigrants from around the world to work the dangerous smelter jobs, and at the adjoining rail yards, and the meatpacking operations that came later. It's now hoping to clean up its environment and experience a renaissance of reconstruction and rebirth.

Cara DeGette produced this story for Colorado Public News as part of a 2012 National Health Journalism Fellowship. Other stories in the series include:

Sure, Dave Oletski knows neighbors who have died of cancer. Lung cancer, breast cancer, other cancers. His grandma died of cancer. His grandfather always blamed it on the smelter. Oletski can count 15 people in a six-block radius of the house he grew up in, all who have died of cancer.

“It’s kind of odd.” he says. Statistically one out of every three people will get some kind of cancer. Still, living in the shadow of a smelter that belched out toxic pollutants probably didn’t help.

Oletski’s grandfather emigrated from Poland in 1915 to work at Denver’s Globe Smelter. For many years that smelter was the largest in North America. Its workers processed the gold and silver and lead and copper that made the mining and railroad barons of the last century into billionaires. Later, arsenic and cadmium were all in the portfolio, netting shareholders of the multinational corporation Asarco billions and billions. That was before the company got sued and was forced to clean up its contaminated 75-acre site, and the surrounding neighborhood.

In 2005, after moving many of its assets overseas, the company declared bankruptcy. The following year, the Globe smelter – which had dwindled from 3,000 workers to dozens – closed for good.

Oletski, now 58, is getting ready to give a grand tour of his home turf on the north side of Denver, in the gritty cradle of the confluence of Interstate 70 and Interstate 25. It’s a 10-minute drive from downtown Denver. He used to think he hated his neighborhood. Now he loves it fiercely.

“If you spend enough time here, you get to love it too,” he says. “We just need a little TLC.”

The struggle is constant. This community battled – and lost – being bisected by two interstate highways. It battled – and won – major lawsuits forcing a multinational corporation to clean up a potential Superfund site in their backyards. Now neighbors are pleading for relief from a toxic chemical smell that routinely stink bombs their neighborhood.

The jury’s out on how this latest assault will be resolved. But, environmental justice advocates note that in Globeville, travesties routinely occur that would never, ever be allowed to occur in richer, politically connected areas of the city.

Founded in 1879 near the banks of the South Platte River, Globeville was once its own town, with its own mayor and city hall. Farming was big in the area, and the smelter drew immigrants from all over the globe – hence its name. Polish, Slovenian, Russian Croatian, Serbian, Czechs, Volga Germans, Hispanics were all recruited to come work the dangerous jobs at the smelter, and at the adjoining rail yards, and the meatpacking operations that came later.

In 1882, Dennis Sheedy, an Irish immigrant who made a fortune in cattle, bought the smelter. He built Sheedy Row to house its workers. He used some of his fortunes from the smelter to build the Sheedy mansion, an opulent family spread miles away, at 1115 Grant St. in Denver’s far tonier Capitol Hill neighborhood.

The Sheedy Mansion, at 1115 Grant St. Dennis Sheedy, an Irish immigrant who made a fortune in cattle, bought the Globe Smelter in 1882. He used some of his wealth to build his opulent family spread in Denver’s Capitol Hill neighborhood. The mansion now houses commercial offices.

Inestimable riches have flowed through Globeville, ending up in the pockets and the bank vaults of the railroad and the gold, silver and copper barons and later, the corporate shareholders. The smelter allowed Benjamin Guggenheim to amass his awesome fortune after he bought a sizeable interest in the Globe Plant in 1888. William Rockefeller, also from a family of great wealth, collected vast riches from the Globe smelter.

During its early years, ore containing precious and heavy metals from Colorado’s famed mountain mines were hauled in by rail to be processed. With its 50-plus structures, furnaces and smokestacks, the smelter loomed over the residential area of Globeville, and along the western edge of the South Platte River floodplain.

Meanwhile, those arriving in Globeville continued the dance that immigrants always do, assimilating to the new world while working to preserve their old-world heritage. Mary Lou Egan, whose family settled here in 1902 and whose blog Globeville Story chronicles the neighborhood’s history, notes these settlers built homes, planted gardens and created the Garden Place School.

They formed ethnic fraternal organizations, built clubhouses for socializing and churches in which to worship. Three of those churches are on the national historical register – Holy Rosary Catholic, the Eastern Orthodox Holy Transfiguration of Christ Cathedral and St. Joseph’s Polish Church. The churches, within a four-block radius, pack the houses on holidays.

In a 1972 account of the early years of Globeville, lifelong resident Larry Betz noted that early on, Denver had a “crush” on Globeville. But, at least at first, Globeville wouldn’t even blush – not even when Denver offered streetcars and a bridge as a sort of a dowry in efforts to annex the town next door.

Eventually, the courting was successful; Globeville became part of Denver just after the turn of the last century. But Betz depicts the marriage between the communities as happy only for a time. By 1921, he writes, “a feeling gradually developed that would stay with Globevilleites for the rest of Globeville’s history. This feeling was that Globeville was a lost area of Denver.”

Among the complaints: There were no cement walks, not any form of a sewer system, there was no gas or many other developments that the main part of Denver had and was getting. “Many of the barefoot children of Globeville had never been to downtown Denver or any other part of Colorado,” Betz writes. “There was no direct route to Denver.”

In 1901, the American Smelter and Refining Company, later renamed Asarco, took over the smelter. The Colorado Department of Health and Environment lists the other compounds – many of them highly toxic – that have since been processed at the plant: arsenic trioxide, cadmium, litharge, test lead, and occasionally thallium, indium, and other high purity metals such as antimony, copper and tellurium.

The smelter wasn’t the only industry in town. Globeville also boasted one of the largest meatpacking rows in the country, lining the South Platte River near the stockyards.

As a child, Oletski remembers the homes of Globeville were “so clean, so spotless.” Nearly everyone had a garden, growing a bounty of fresh veggies. But the neighborhood was filled with the odors from the meatpacking and the rendering plants as they cooked down the remains of animals. The blood, he says, made for wonderful fertilizer for the rose bushes, but the smell, oh the smell.

When he was 15, Oletski went to work on the kill floor. “Most of the guys were drunk. They had to be, the work was so hard,” he says. “We were the beef capital of the country.”

After work, he hung out in the Blue Blaze bar on 52nd and Washington streets. It was right across the street from the smelter, on the border of Adams and Denver counties – no man’s land. Oletski wasn’t old enough to buy booze to take home. But they let him drink there, and play craps and card games, after putting in the kind of backbreaking work the bar owners knew he’d done all day long, killing and processing 1,200-pound animals into meat that would end up on everyone’s dinner table.

Injuries on the meatpacking kill floor were so common that the guys would wait until five or so of them were hurt. Then they’d all carpool to the hospital. One day Oletski slipped on a wet floor, and on his way down whapped his chin on a stainless steel wheelbarrow. The pain that ripped down his spine marked the beginning of a life of back problems.

Oletski eventually left the kill floor and went into business for himself, building wooden pallets. Then he worked at the nearby Nabisco plant making high quality dog biscuits. When it closed, he found himself also divorced, with child support payments. So he went to Laramie, Wyo., 140 miles north, and worked for a refrigeration company. He reinjured his back. Then he discovered a lucrative business exporting reclaimed Levi’s jeans overseas, which he did for 10 years. Eventually he went to work laying underground utilities through Bailey and Conifer in the mountains southwest of Denver, until he hurt his back again.

Meanwhile, the face of Globeville was changing. By 2010 the ethnic makeup of the neighborhood was 68 percent Hispanic. Many of them were new arrivals, replacing the first wave of immigrants from Eastern Europe.

Homes in Globeville, 1½-story bungalows with front porches, constitute some of the last affordable housing stock in Denver. In 2000, just over 60 percent of the homes in the community were owner-occupied – compared to about 50 percent for all of Denver. In 2005, the average price of a home in Globeville was $131,226.

Seven years ago Oletski bought his parents’ house in Globeville. He came home, but quickly determined he was not long for that world. “I’m leaving; this place sucks. I hate it,” he thought. Then he got to driving around the neighborhood. He looked at it through a new set of eyes, remembered his roots, saw the possibilities, and got stoked. He rethought his position. Last year he became the president of the Globeville Civic Association.

“There’s something about Globeville. This place is just filled with a rich history, special people – karma people,” he says. “You just want to give it a hug.”

Oletski hasn’t been alone. Groundwork Denver, a nonprofit that works to improve the physical environment and promote healthy neighborhoods, has arrived and is making its way through the neighborhood wielding industrial-strength elbow grease. The Superfund site that the smelter left behind is also being cleaned up – though neighbors say they have no idea what it might become.

Later this year, President Jimmy Carter and his wife Rosalynn will arrive in Globeville to undertake a massive Habitat for Humanity project. The plan is to build 11 new homes and repair 15 more in the neighborhood.

There are two McDonald’s restaurants in Globeville, population 3,687, and a third just over the Adams County line. But there is no nearby grocery store. There is no master plan defining the future of one of the oldest neighborhoods in Denver. This draws criticism from environmental justice advocates like Michael Harris, director of its Environmental Law Clinic at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law.

“There is no good excuse that Denver’s ‘last frontier’ cannot be planned and built sensitively and intelligently for the 21st century,” Harris co-wrote in a recent Denver Post opinion piece.

“It’s a classic political disempowerment,” he says.

City councilwoman Judy Montero, who has represented the community for nearly 10 years, says a comprehensive plan for Globeville is in the works, but that it’s key that the community drive the process.

“The vision is what the people from Globeville want,” she says. “I don’t want it to be my process. I want it to be the peoples’ process.”

In recent years, residents of Globeville have watched as, just a few miles away the 4,700-acre site of the former Stapleton International Airport has been redeveloped into the largest residential neighborhood of Denver, with an impressive infrastructure of streets and sidewalks, homes, shops, schools, churches, restaurants, a top-of-the-line recreation center, bikeways and open space.

They have watched as other formerly polluted neighborhoods just minutes away – Highlands, River North, Lower Downtown, Ballpark and Union Station – have undergone a collective renaissance of reconstruction and rebirth.

Globeville in 2013 is a stark contrast. The roads connecting it to other neighborhoods are a complicated maze. Washington Street – the gateway into the community – is a rutted, two-lane mess. Residents have been asking officials to widen and improve it for more than 20 years. They’ve asked for basic things, like sidewalks, bus stop benches, trash cans for their alleys.

“They said they would do it, then they said no, no. There is no money, there is no money,” says Margaret Escamilla, the former president of the neighborhood association, who for many years was considered the unofficial mayor of Globeville.

“Everything is a fight here.”

This story was originally published on The Colorado Public News, January 21, 2013

Photo Credit: Western History/Genealogy Dept., Denver Public Library