Cause of death: ‘Lack of empathy.’ Medical neglect in Florida’s juvenile justice

This article and others in this series were produced as part of a project for the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship, in conjunction with the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Powerful lawmaker calls for juvenile justice review in wake of Herald series

Juvenile justice chief defends agency, calling abuses ‘isolated events’

An officer used a broom to beat juveniles into submission. They called it ‘Broomie.’

NAACP demands reform as lawmakers plan tour of lockup where youth was fatally beaten

Criminal record? Horrible work history? Florida juvenile justice would still hire you

At this juvenile justice program, staffers set up fights — and then bet on them

Dark secrets of Florida juvenile justice: ‘honey-bun hits,’ illicit sex, cover-ups

Lightning blasted his shoes off — and illuminated a pattern of abuse by staff

How small rebellions by Florida delinquents snowball into bigger beatings by staff

FIGHTCLUB: A Miami Herald investigation into Florida’s juvenile justice system

Andre Sheffield ached, trembled, limped and finally defecated on himself at the Brevard juvenile lockup. Nobody paid him much mind — until he died of bacterial meningitis. Emily Michot

JACKSONVILLE — Andre Sheffield thought the tomatoes were making him sick.

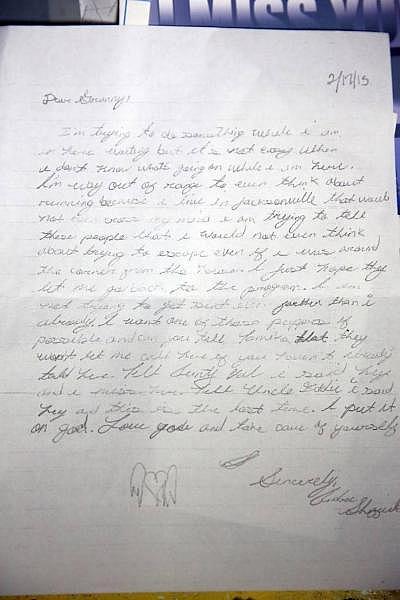

He had nursed a nasty stomach ache for a couple of days at the Brevard Regional Juvenile Detention Center, but even in pain made time to write a letter to his grandmother, the woman who raised him, promising to live a better life from then on.

“This is the last time,” he said and gently reminded her that she needed to take care of herself. He told her that he loved her and that he knew God.

And he signed off with a sketch of a heart embraced by angel wings.

The letter began, “Dear Granny,” written in Andre’s hand, cursive, and dated Feb. 17, 2015.

It arrived two days after his death. He was 14, the victim of untreated bacterial meningitis.

This is the last letter that Berlena Sheffield received from her grandson Andre, 14, written two days before his death. He signed the letter with a heart adorned with angel wings. Emily Michot

Andre’s death is one of several instances over the years in which questionable judgment and substandard medical care have led to painful, even deadly, consequences for confined youths.

“He would have been better off if he would have stayed home. He would’ve been out there in the streets ... but to have to die like he did,” says Berlena Sheffield, Andre’s grandmother and legal guardian, her voice trailing off.

A total of 400 complaints of medical neglect have been investigated by the Department of Juvenile Justice since 2007, with 39 of them substantiated and another 23 inconclusive. Andre’s death was not among the medical neglect cases: An inspector general report looked only at violations of policy and rules, substantiating three of them.

Allegations have ranged from critically slow treatment to errors in prescribing medications to failure to provide medical screenings.

A close look at the most tragic cases reveals a disturbing pattern: Officers, youth care workers and even nurses often refuse to believe youths — or their own eyes and ears — when confronted with an imperiled detainee. A 12-year-old boy was fatally smothered by a 300-pound worker who claimed the boy was “playing possum” when he shrieked that he couldn’t breathe.

Two boys died slow, excruciating deaths — one of appendicitis, the other of a brain injury — while officers concluded they were “faking.” After another teen slowly died of a heart condition, a worker explained that he thought the gurgling sounds from the unresponsive youth were a “prank.”

DJJ’s secretary, Christina K. Daly, said the safety and well-being of detained youths is the agency’s highest priority.

“When incidents such as these occur at DJJ, the staff statewide experience the pain and sorrow of losing a youth in our care. It is not a matter that is taken lightly nor quickly forgotten,” she said.

In one of the more striking non-fatal cases, a teenager at the Gulf Coast Youth Academy in Fort Walton Beach repeatedly complained — on at least 13 different occasions — of excruciating pain in his right leg. Staff gave him pain relievers but never sought to determine the source of the pain.

Three months after his first sick-call, the boy’s right leg was amputated. The delayed diagnosis was cancer of the bone. The disease had metastasized to his lungs, requiring chemotherapy, medical records showed.

In May 2012, two lockup officers were fired in Collier County and a third was suspended after they waited too long before taking a teen to the hospital for his broken jaw. The boy had been jumped when staff let another youth out of his cell. Two officers went to an on-site nurse to have the boy’s blood cleaned from their uniforms and to treat minor scrapes, but failed to tell the nurse where the blood had originated.

More than two hours passed before the detainee went to the hospital, where he needed surgery, a report said.

Questionable judgment can extend to mental health issues as well.

In February 2014, an officer trainee was stationed just outside a 14-year-old’s cell at the Manatee Regional Juvenile Detention Center, where the boy was under observation. The youth tied a bedsheet around his neck. The officer did not enter the cell to remove the homemade noose. Instead, she asked another officer to snatch the sheet, which the colleague neglected to do. The teen choked himself until he vomited and passed out.

“She didn’t think the youth was serious,” a DJJ report said.

‘Stop faking’

The following July, a Broward public defender complained that a youth in that county’s lockup had to be rushed to the hospital after workers ignored “repeated vomiting and complaints of stomach pains” until the boy required emergency surgery. “Most troubling,” wrote the county’s top juvenile public defender, Gordon Weekes, “is that staffers instructed the child to ‘stop faking.’ ’’

Gordon Weekes. Emily Michot

On Dec. 11, 2014, a 15-year-old charged with armed robbery arrived at the Broward Juvenile Assessment Center en route to the county’s lockup. Detention center staff refused to accept him, saying he had yet to be “medically cleared” — part of the standard intake process. Later, officers fetched the boy anyway, a report said.

He came with clearly swollen eyes and a bag of prescription medication for a life-threatening kidney disorder that required dialysis beginning at age 3. Nurses declined to medicate the boy, saying the drugs were out of date.

In a Dec. 15 email to the lockup’s superintendent, Weekes said the boy’s mother told the arresting officer that her son was in a “fragile medical state” and needed a drug infusion early the next morning. That evening, Weekes wrote, the mother called the lockup and again explained his medical history. She “stressed that her son was very ill.”

DJJ says the call was to the assessment center, where incoming youths are processed, not the lockup.

In any event, the mom said she was told “there was nothing DJJ could do for him.”

When the boy’s mom spoke with lockup staff the next morning, she again reminded them about his scheduled infusion, Weekes said. She was told he’d have to go to court first.

By that point, the boy’s eyes were nearly swollen shut, and his body was bloated. A lockup nurse sent him to the hospital.

When the detention center superintendent later asked a supervisor why he kept a clearly sick boy locked up with “no sense of urgency,” the officer “shrugged his shoulders and remained silent,” a DJJ administrative review said.

A Broward judge didn’t shrug two years later in a case involving a boy with serious diabetes.

In December 2016, Broward Juvenile Court Judge Stacey Schulman ordered the release of 14-year-old Denzel Glasco, because she was convinced that DJJ could not appropriately treat the boy’s diabetes. Schulman said she was told that, even though his father brought insulin to the lockup, the detention center lacked syringes.

Denzel Glasco had to be sent to the hospital when the Broward Regional Juvenile Center couldn't monitor his diabetes or administer his insulin. Emily Michot

“If they hadn’t gotten him to the hospital, he could have died,” said the father, Darrell Glasco.

In an internal email obtained by the Herald, Schulman said she was “VERY concerned for this child’s well-being. ... I cannot imagine Denzel is the first child with diabetes to come into DJJ’s custody.”

For Denzel, who was diagnosed five years earlier and attended Pompano Beach Middle School, the stay in the lockup was unnerving.

“I felt like my life was in danger,” he told the Herald. “They didn’t know a thing about diabetes.”

When in doubt, send them out

Juvenile justice administrators do not directly provide healthcare to youths in custody. The state is in the process of consolidating medical care management into four regions that cover the 21 detention centers the Department of Juvenile Justice operates. Private providers that run 53 residential commitment programs each are responsible for routine and emergency medical care, and most sign subcontracts with other companies.

In an interview with the Herald, DJJ’s Daly acknowledged the state’s history of sometimes tragic neglect. “I will tell you, there’s nothing worse than the phone ringing in the middle of the night. But we learn from those experiences, and it allows us to really focus our efforts on training of staff for medical situations,” she said.

“It’s heartbreaking,” she added, in an unusually emotional moment in the interview. “One child being victimized in the system is too many.”

Detained youths represent a serious test for caregivers and officers, Daly said. “Many times when kids come into the detention centers, it’s the first time they’ve ever seen a doctor in many, many years — probably since they got their shots to go to school as a young child.”

Still, there’s little excuse, Daly said, for detained youths to be denied necessary medical care. Administrators have been emphatic that direct care staff err on the side of safety, not cost-saving, she said.

“It’s common sense. We have good policies in place, good procedures, practice. If they’re not followed, they’re worthless.”

She added: “My motto when I’m in and out of programs is: ‘When in doubt, send them out.’ ”

Three months after Andre Sheffield’s death, a state juvenile justice investigation placed blame on the staff of the 40-bed lockup, concluding that guards had ignored the boy’s complaints, along with his growing list of symptoms, before he was found dead in his cell. The 50-page report also faulted the lockup’s top officer for not ensuring that the staff was properly trained in sick-call policies and procedures.

Six staff members were disciplined and a seventh, a nurse, was fired after she refused to be interviewed by DJJ investigators.

A lofty promise and harsh reality

In one of the darkest moments of Florida’s juvenile justice history, an Opa-locka teen died a cruel, filthy, painful death at Miami’s lockup. Omar Paisley’s persistent moans and cries were ignored until it was too late. He died of an undiagnosed burst appendix.

Two dozen juvenile justice officers and administrators were fired or resigned after Omar’s June 2003 death. A new DJJ secretary promised the agency would “treat every child as if he was your own.”

Gina Jones holds a photo of her son Martin Lee Anderson taken just before he entered a Panhandle boot camp. In 2006, he stopped breathing during a restraint at the camp while a nurse stood by and declined to help. Ken Helle-Tampa Bay Times

Death followed the promise three years later: In 2006, Martin Lee Anderson stopped breathing during a restraint at a Panhandle boot camp while a nurse stood by and declined to help.

Death followed the promise eight years later: In 2011, Eric Perez was thrown to the floor on his head by an officer while “horse playing.” For hours, Eric exhibited signs of a serious head injury, vomiting and hallucinating. By the time staffers at the Palm Beach County institution responded, he was dead of a brain injury.

Death followed the promise 12 years later when Andre Sheffield died. Fast forward six months and Elord Revolte was jumped by a group of boys, punched, and stomped in the Miami detention center. Although he’d been brutally beaten, lockup administrators waited nearly 24 hours before taking him to the hospital, where he bled out.

In 2005, during an unprecedented effort to improve medical care in the wake of Omar Paisley’s death, Harvard-trained internist and pediatrician Shairi Turner signed on as the agency’s first chief medical director. Her hiring was announced with fanfare by then-DJJ Secretary Anthony Schembri. Turner remembers being struck that Omar did not die so much of a ruptured appendix as of a lack of basic attention to his needs.

“Cause of death? Lack of empathy,” she said in a recent interview.

“How could you look at a child who is not breathing — or not doing well, or dying, or sick — and not feel some sort of empathy?” she asked.

As the only doctor on staff at the agency’s headquarters, Turner, along with a small staff, rewrote a 400-page health services manual, as well as manuals for substance abuse and mental health treatment, She also helped shepherd a significant hike in healthcare spending, placed defibrillators in every detention center and insisted on hiring more doctors and nurses.

And then she watched helplessly as it began to erode four years later. During the financial crisis of 2009, Turner said the agency began to slice away at some of the progress she’d overseen.

“We were losing funding and being forced to cut corners back then. I could not see my way clear to cutting corners I had worked so hard to bolster.”

Unwilling to watch her efforts evaporate but unable to stop it, Turner moved on. She now does consulting work on the importance of understanding and treating childhood trauma.

“If what we did saved one life, then all the work was worth it,” Turner said. “But I do believe we impacted far more than one child.”

The death of Andre

In Jacksonville, Andre’s grandmother shares his story from her living room, now a shrine to the dead teen. A grandmother of 12, Berlena Sheffield said he was the curious and devilish one, and loved Gospel music. She recalls once when she was particularly worried, he retrieved a copy of a pocket-size Bible.

“Read this, Granny. This 5-year-old is telling me to read the Bible,” she said.

Sheffield, who spent a lifetime cleaning other people’s houses, adopted Andre when he was 5 — a special needs child, she called him, diagnosed with attention-deficit disorder. She raised him in a worn, teal clapboard house on Cesery Boulevard.

His mother lost custody of all six of her children because of a disabling drug habit. His mom’s travails scarred Andre.

By the time he was 12, Andre was running the streets and refusing to take his prescription medication. The meds gave him headaches and insomnia, he said.

The neighborhood police knew him by name. Each time officers brought Andre home, he would apologize to his grandmother and promise to do better.

Released from one detention, Andre broke into a neighbor’s house, violating probation. A judge committed him to the Melbourne Center for Personal Growth on May 29, 2014.

Every day, Sheffield prayed for her grandson’s spiritual protection and his earthly rehabilitation.

Ten months into the program, with his release date in sight, Andre was accused of trying to run away. That is how he came to be in the detention center’s East Module the week of Feb. 12, 2015. That’s where he got sick.

Andre’s last letter home was dated Feb. 17. He told his grandmother to keep a puppy from the family dog’s new litter for him. He asked her to say “hey” to family members, and promised that “this is the last time. I put it on God.”

Berlena Sheffield told both a DJJ inspector and the Herald that her grandson called her almost daily and that “each time she spoke to him, he complained about diarrhea and headaches.”

But for a kid who was slowly dying, Andre left virtually no record at the clinic. On Feb. 12, he was admitted. The next day, his medications were logged in: Lexapro, an antidepressant, and omeprazole, for gastric reflux. A Feb. 19 “practitioner’s order” that Andre be placed on bed rest was found, but the doctor whose signature is on the order later admitted he signed it three days later — after Andre was already dead — without ever having seen him.

Also on the 19th:

7:55 a.m: Nurse Karen Rainford documents that, according to an officer, Andre had defecated on himself. Andre told her that his stomach hurt and he was having migraines. She notes he was “calm and cooperative,” but then he began to hyperventilate. She gives him Tylenol, two tabs, and encourages him to drink fluids and rest in bed.

9:10 a.m.: Rainford checks on Andre, and another officer says he is “lying on the floor with a cup in his hand and drinking water.” Andre returns to his bed with no distress noted.

9:30 a.m.: Rainford says she sees Andre lying in bed on his back with his eyes open. Again, no distress is noted. Andre tells the nurse he is cold, yet Rainford notes his skin is warm and dry. She tells him to put socks on his feet.

11:30 a.m.: Rainford goes to Andre’s module, where officers have declared a Code White, or medical emergency. Andre has no pulse.

Sheffield, 77, remembers the apologies. They came fast and furious. The voice on the other end tearfully said, “I am sorry.”

Sheffield was confused, then asked herself, “Is this lady trying to tell me my boy is dead?”

She was.

“Following the death of this youth, the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice took immediate action,” Daly told the Herald. Among other things, the agency required that all of the lockup’s staff be retrained in sick-call procedures and the oversight of detainees who are ill.

‘Deliberate indifference’

DJJ investigated Andre’s death from an inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain.

Beyond the dearth of medical records, investigators confronted two distinct realities: The officers in whose care Andre was entrusted uniformly insisted he showed no signs of distress until the day before he died.

One officer — among many who denied knowing Andre was ill — said he “never noticed anything unusual about youth and the youth never complained about not feeling well or asked for a sick-call.”

The other reality: Detainees told a starkly different story, but were consistent among themselves. They said Andre had complained repeatedly of leg, stomach, head and neck pain. That he was shaking and limping around the module. That he suddenly fell “sideways” into a chair. That he defecated on himself. That he banged his head against a chair, and explained — wrongly — that he had a metal plate in his head.

In a familiar refrain, one youth said a nurse told him that Andre “was lying about his complaints [because] youth sometimes do that so they can remain in bed.”

Three boys told DJJ that Andre asked to be placed on sick-call. The officers denied that, and the sick-call logs show no such request. But investigators later concluded the sick-call program was, at best, haphazard, that some sick-call requests were never entered, and that others were entered hours late.

“Lack of oversight,” DJJ called it.

A state Department of Health complaint against Rainford noted that the nurse “lacked reasonable medical judgment and failed to recognize [Andre’s] signs of physical distress as emergent and requiring further medical attention.”

“They let my boy die,” Sheffield says.

Andrew Bonderud, Sheffield’s attorney, said the actions of Brevard’s staff amounted to “deliberate indifference.”

“There was a long list of errors committed by numerous people, any one of whom could have broken that chain and potentially saved Andre’s life,” he said.

The litany of errors continued even after he died. The inspector general criticized the lockup for tossing Andre’s bedding — potential evidence —into a dumpster, where it “had been picked up by waste management before law enforcement could retrieve it.”

Lockup administrators were criticized for the same lapse after Omar Paisley died.

The department paid for Andre’s funeral.

He was buried in a white suit in a white casket in a grave without his name in Restlawn Cemetery, the third generation of Sheffields on grounds shaded by old oak trees draped in Spanish moss.

There is no etched stone with his birth and death dates. Sheffield plans to eventually add the headstone, a way to tell the world he was somebody’s son, grandson, brother.

“Won’t be just like they threw him away,” she said. “Like he was not loved.”

[This story was originally published by the Miami Herald.]