Chapter 1: Poor Health: A frayed safety net

Sean D. Hamill wrote this report for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette as a 2013 National Health Journalism Fellow and Dennis Hunt Journalism Fund Grantee. Other stories in this series include:

Why Wilford Payne is known as the Johnny Appleseed of local health centers

Access to specialists out of reach for many in Pittsburgh region

Braddock Mayor John Fetterman stands near the former site of the borough's sole hospital.

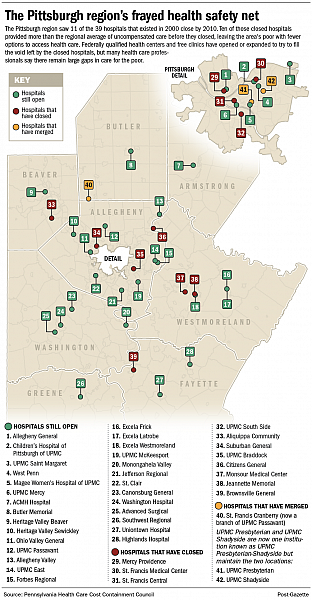

More than a quarter of the hospitals in the Pittsburgh area closed in the first decade of the 21st Century, drastically reducing the amount of charitable care available to the poor.

The failure of the remaining hospitals to provide adequate care to low-income patients and the inability of free and government-funded clinics to fill the gap has left the region's health safety net badly frayed.

The closures of 11 of 39 hospitals here between 2000 and 2010 left the region's poor "worse off," said Wilford Payne, executive director of Primary Care Health Services in Pittsburgh, which runs 11 federally qualified health centers in Allegheny County.

"When you think about a St. Francis that took care of so many people with mental health needs, or a Mercy Providence that was one of the few hospitals that provided real charity care, and South Side, and Braddock, and Aliquippa and on and on," said Mr. Payne, who has headed Primary Care Health Services for 37 years. "Everyone one of them did some charity work and reached out to poor people and did their share."

"That doesn't happen now," he said.

Why?

"Everyone knows you go broke providing health care to broke people," said Braddock Mayor John Fetterman, whose community lost its hospital in 2010.

Broke people usually have no insurance or they are on Medicaid. Hospitals and doctors lose money serving such patients, since they get no reimbursement or reimbursement below levels they'd get from better insured patients.

That's why hospitals seek to avoid poor patients.

In Pittsburgh, St. Francis Central, St. Francis Medical Center and Mercy Providence — all Catholic institutions now closed — once were routinely among the largest providers of uncompensated care in the region. (Uncompensated care includes charitable care and bad debt.) St. Francis Medical Center, for example, provided three times the region's average percentage of uncompensated care in its last year of operation in 2002.

"The problem as always was money," said Sister Ann Carville, who was vice chair of St. Francis Health System when UPMC bought and then tore down St. Francis Medical Center in Lawrenceville. "We really lived by the principle that we wouldn't turn anyone away, and we didn't."

But now only one city hospital, UPMC Mercy, is in the top 10, although the region's largest concentration of poverty continues to be in city neighborhoods.

UPMC Mercy put 4.63 percent of its patient revenues into uncompensated care in 2013, according to state data. The city's five other hospitals provide less than half that percentage of their revenues to uncompensated care. UPMC Shadyside-Presbyterian, Allegheny General, West Penn, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC and Magee-Womens of UPMC all provide around 2 percent, putting them in the bottom half in uncompensated care in the region.

Will Cook, president of UPMC Mercy, said the long history of the Sisters of Mercy "built our reputation over time and people in need are naturally drawn here."

"UPMC has not funneled [poor] patients here," he said. "But I think we should. Because we do potentially provide better depth and breadth of services to this community."

He said government insurance programs that cover most poor children and many poor women mean Magee and Children's have lower charity care levels.

Liz Allen, chief financial officer for Allegheny Health Network, the parent company to Allegheny General and West Penn, attributed their low percentages to "the way it's calculated" but offered no details.

Of the 11 that closed, all but Mercy Jeannette provided higher than the regional averages of uncompensated care.

Most hospitals locally say they will provide free charity care to patients with incomes up to 200 percent of federal poverty level (about $23,000 for a single person) and discounted care, typically on a sliding scale, for patients with incomes of up to 400 percent.

Though no hospital in the region would say that they seek to avoid poor patients, there are obvious and not-so-obvious ways to discourage them from accessing health care.

Practices used by local hospitals include using narrower financial parameters; making patients reapply for free or discounted care frequently; not listing financial assistance programs or applications online; and reporting patients to credit bureaus. Though it is rare nationally, nine hospitals in the Pittsburgh area routinely report patients with delinquent bills to credit bureaus and eight do not put financial assistance information on their websites.

Free clinics and federally qualified health centers are now trying to fill the gap left by the loss of hospitals and doctors. There has been a steady increase in the clinics: There was one FQHC in Allegheny County, where the bulk of the region's poor and uninsured reside, when Mr. Payne came to town in 1977; now there are 22. From just one free clinic in 1994 — the Birmingham Free Clinic on the South Side — there are now five in the county, with at least three more in surrounding counties. But it's not enough to address the unmet needs, Mr. Payne said.

"I don't think we could ever pick up what the hospitals did," Mr. Payne said, "no matter how many of us there are."

This article was originally posted in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette