A Checkup On One Of America’s Most Expensive Patients

Sue Beder has had MS [multiple sclerosis] since she was 18 years old and she is one of the country’s most expensive patients. Beder recently signed up with an agency that will try to improve her health while working under a budget, sometimes called a global payment. If health care on a budget doesn’t work for high-cost patients such as Sue Beder, it may not make sense for any of us.

In April, we introduced you to one of America’s most expensive patients. Stoughton’s Sue Beder is 66 and has had multiple sclerosis since she was 18. She sees half a dozen doctors, takes 21 prescribed medications, and is typically in and out of the hospital twice a year.

Beder is one of the 5 percent of patients we often hear about who account for half of all health care dollars in the United States. As one of the most expensive patients, Beder is at the epicenter of Massachusetts’ efforts to save money while improving her care.

Late last year, Beder signed up with an agency, Senior Whole Health, that receives the money Medicare and Medicaid expect to spend on Beder and pools that into one budget. It’s an approach the state plans to expand to 110,000 disabled patients across Massachusetts. Senior Whole Health pledges to spend less than the government would spend and, in exchange, the agency gets to decide how best to spend the money to keep Beder healthy.

Beder couldn’t have been happier with the move. The agency put handrails in her bathroom and started buying all her vitamins and lotions. It supplied adult diapers so that she wouldn’t get out of bed at night and risk a fall. The agency is doing all this to help Beder stay home. That’s where she wants to be, and it’s cheaper than moving her into a nursing home.

So is this idea working? Is spending more money up-front on this home-based care helping Beder avoid costly medical care?

Here’s a hint: We begin the second part of our series at Epoch Senior Living, a nursing home in Sharon. The goal is to get Beder back to her cozy bungalow in Stoughton. If she can recover and return there, it will likely be her last chance to try living at home.

A Two-Month Medical Journey

Beder rocks forward, trying to make the transition from wheelchair to walker.

“It’s hard again today,” Beder says, her voice cracking with tension.

“So, push it [the wheelchair lock] forward until you hear the click, then you know it’s locked,” coaches Sharon Lerner, an occupational therapist at Epoch.

“Forward,” Beder mutters. “Oh, OK, forward.”

Beder’s been in and out of this nursing home and several hospitals for two months.

It all started with this: Beder wasn’t getting enough to drink and became severely dehydrated. An aide found her slumped in a chair. “I couldn’t hear that well,” Beder recalls, “and I couldn’t swallow much and um, I’m trying to think what happened this time, but I knew I had to go to the hospital.”

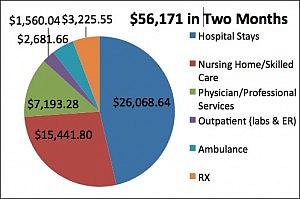

Now, after three separate hospital stays, repeated recoveries and $56,171 in bills, Beder is cleared to go home. But only if she agrees to some difficult changes.

‘It Wasn’t Working Out Before’

Three nurses, a social worker and Beder sit around a small conference table at the nursing home. They’ve gathered for a required discharge planning meeting. Before Beder can go home, her main nurse at Senior Whole Health, Judy Tremblay, wants to make sure the seemingly small problems that triggered Beder’s long, expensive medical journey won’t happen again.

All eyes turn to Tremblay, who sits up straight in her chair. “I want to talk, Sue, about two phone calls I got,” Tremblay says. “One phone call was from your mom.”

Beder’s 93-year-old mother told Tremblay why Beder wasn’t getting enough to drink. Beder was letting her personal care attendants, or PCAs, work hours that were convenient for them, but not for her. Beder, her mother told Tremblay, usually wakes up around 6 a.m., but her PCA wasn’t arriving until 10 a.m.

“And between the hours of 6 and 10 you really have no one to take care of you, to help you get to the bathroom, to help you get something to eat or drink,” Tremblay says, her voice rising with urgency. “[And your mom says] that you had falls during the 6 to 10 period.”

Beder jumps in to defend Jen, her main PCA. “She always says to me, if I need her, I have her phone number, to call her,” Beder says.

Tremblay gives Beder one of those looks. Beder is crestfallen. She thinks of Jen as family and depends on her for emotional support.

“She happens to be a very wonderful person in my life, it’s just that she has a daughter,” Beder says, hoping Tremblay will relent. She doesn’t. Beder’s voice becomes plaintive. “I can talk to Jen and tell her I need her. Does that…?”

Beder glances up and sees Tremblay is still giving her that tough-love look. It turns out that another PCA, the one who comes on weekends, wasn’t arriving at Beder’s home until 4 p.m.

“Sue, this is all about you,” Tremblay says firmly. “This is about what you need. So it’s just not been working out.”

“Right, no, it hasn’t been working out,” Beder agrees.

Beder looks defeated as Tremblay says she may have to hire a new team of aides and put them on a different schedule. Jennifer Cooperman, a social worker at Epoch, steps in to reassure Beder.

“You need to know you’re not trapped,” Cooperman says. “If something upsets you tonight or whatever, we still work towards the goal of getting you home and keeping you home safely. Does that make sense?”

“Yes,” Beder says, “that’s good.”

Beder’s discharge plan requires a visit to her primary care doctor. He’s a key part of Beder’s team and will be part of the decision about whether she can remain at home.

Dr. Joseph Kagan has been treating Beder for more than 10 years and her mother for almost as long. “You been doing OK?” Kagan asks, bursting into the room with a big smile. “I know you were in rehab for a while.”

“Oh my God, two months,” Beder tells Kagan, “and I did some silly things.”

“Well, the issue was you were not really well at the time,” says Kagan, who spoke to some of the nurses and doctors who treated Beder, “and you were making decisions you normally would not have, so I understand all of that.” Kagan moves through a routine exam.

“The main thing is,” he continues, is that “a lot of it’s behind us. Right now, your mind is as clear as a bell. We’re going to start winding down some of these medicines. We’re going to see how you do.”

Kagan reviews Beder’s 21 prescriptions. He cuts her dose of sleeping pills so she’ll be less groggy and less likely to fall if she gets up in the night. But he agrees to increase the strength of Beder’s anti-depressants after hearing about the upheaval with her PCAs and a cat who was gone when Beder got home.

“Oh, I feel so bad” about the cat, Beder says. “I’m very depressed.”

“Yes, but you just pick up the pieces and move on, and you’ve always in the end been very courageous,” he tells Beder, holding her hand. He tell her to come see him again in a month.

Returning Home To Many Changes

Beder makes it back home. Tremblay, her nurse, is there to reinforce the rules. Beder must drink regularly, avoid falls, and keep her PCAs on the agreed schedule.

“Sue knows that if this fails, the next step is long-term care,” Tremblay says.

Beder has a new PCA, Ernestina Depina, who is just arriving with an armload of groceries, including Beder’s new favorite drink, diet cranberry juice.

“Oh hello,” Beder tells Depina. “Look how pretty she is, just like Sophia Loren, but she doesn’t even know Sophia Loren.”

Depina does know the Heimlich maneuver. She performed it on Beder in her first week on the job.

“I just have a habit of putting so many things in my mouth. And I’ll try to start to talk and, oh, it was just awful,” Beder recalls. “Before I knew I was choking, she [Depina] said, ‘Sue, do you want to go to the hospital?’ And she got me frightened.”

Beder refused Depina’s plea that she go to the hospital because Beder was worried she’d end up in another spiral of hospital admissions and readmissions. If that happens again, Beder may be back in the nursing home for good. There are no programs that pay for 24-hour care at home, Tremblay tells her. If a patient needs that, they go to a nursing home, unless they can afford to pay for round-the-clock care on their own.

Beder, Tremblay and others involved in Beder’s care discussed whether she should have left the nursing home this time.

Says Tremblay: “The question was, how feasible was it for her to come home? Sue is competent. Legally she can make her own decisions. Whether they be decisions other people would make, it’s not up to us to judge that. She wanted to be home.”

As in our first story, Beder is still falling regularly. She calls the Stoughton Fire Department about six times a month to come pick her up off the floor and place her in a chair or back in bed. Tremblay and Beder keep trying to come up with solutions.

“You have to have an open relationship, because I have to be able at any time to come in and say, ‘Sue, this isn’t working,’ ” Tremblay says. “You’ve had this many times, rescues come here. Next time it could be a fractured hip.” We have to have that relationship, she continues, so that Beder will trust her one day when she says, “this is no longer going to be possible.”

“I do trust you,” Beder says.

There’s no sign yet that caring for Beder under a global payment is saving money:

$56,170.97 – Sue’s hospital and nursing home-related expenses

$15,709.00 – What Senior Whole Health received for her care over the period

$40,461.97 – What Senior Whole Health lost for this period

But if Senior Whole Health weren’t trying, Beder would probably already be in a more expensive nursing home full-time. The agency says it often takes a few years to get to know a patient and figure out what will work to keep them healthy at home.

Still, Beder is a sign that controlling costs without sacrificing care for the country’s most expensive patients can be really hard.

This article was originally published in http://www.wbur.org/

Related Content:

Exploring Global Payments and Building a Network of Savvy Patients

Trying to Control Health Care Costs in Massachusetts

In Massachusetts, Support Grows for Medical Homes For Mental Health Patients