At The Crossroads, Part 1: A tale of two epidemics

When it comes to hepatitis C, we’re standing at a crossroads — a place where two epidemics are about to meet. And what happens next is critical. “The success we have over the next five to ten years is going to depend on what we do over the next one to two years,” says Dr. John Ward, who oversees all things hepatitis C at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Kristin Gourlay reported this story as a fellow in the 2014 National Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. Additional parts of this series include:

At the Crossroads, Part 2: Finding hep C infections before it's too late

At The Crossroads, Part 3: As old hepatitis C treatment fades out, new treatments stoke hope

At The Crossroads, Part 4: New hep C drugs promise a cure, for a big price

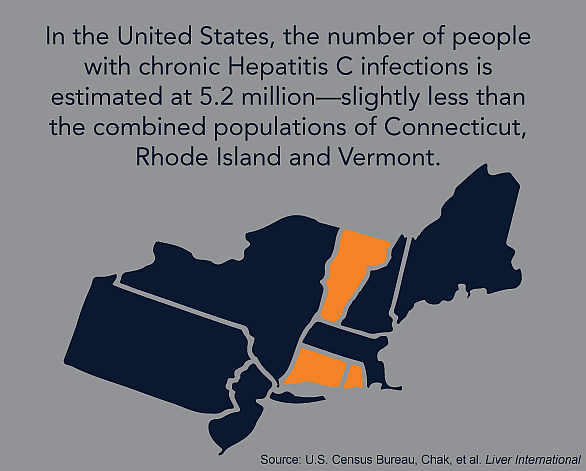

Note: This estimate includes people not typically counted by national health surveys. The CDC estimates about 3 million Americans are infected but doesn't include people who are incarcerated, on active military duty, or in nursing homes. Credit Jake Harper / RIPR

One infectious disease – Ebola – is dominating the headlines now. But there’s another that affects far more people around the world, including here in the U.S.

Hepatitis C infects an estimated five million Americans, though most of them don’t know it, because it takes years for symptoms to emerge. Now, deaths from hepatitis C are on the rise in baby boomers. And throughout New England, new infections are creeping up among a younger generation. Less than a year ago, their only options for treatment were complicated regimens of injections that didn’t always work. But brand new drugs could change everything. That is, if the cost doesn’t break the bank.

We’re kicking off a new series called “At The Crossroads: Hepatitis C On The Rise And The Fight To Stop It.” Rhode Island Public Radio health care reporter Kristin Gourlay takes us inside the epidemic in Rhode Island and beyond.

------------

This very moment, we’re standing at a crossroads. A place where two epidemics are about to meet. And what happens next is critical.

“The success we have over the next five to ten years is going to depend on what we do over the next one to two years.”

Meet Dr. John Ward. He oversees all things hepatitis C at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And what he sees at this crossroads is a crisis.

“One, we have an epidemic of hepatitis c mortality. We have an increasing number of people dying from hepatitis c among the baby boom population who were infected decades ago.”

Baby boomers make up the majority of the estimated five million people who have hepatitis C. Most caught the disease – from sharing needles, or a blood transfusion, most likely - years before we even knew about the virus. And long before we learned to keep it out of our blood supply. It can take decades before symptoms emerge.

“Now their liver disease is so advanced they’re becoming ill from it.”

Hepatitis C now kills more people than HIV. But Ward says new infections are on the rise among young adults, mainly people who inject drugs. More than a dozen states have reported a 200 percent increase in new cases in the past couple of years.

“So we’re getting a second boom generation of hepatitis C.”

So, two generations of people with hepatitis C meet at this crossroads. And so, too, are two generations of drugs meant to cure them. The older generation -- a complicated regimen of injections and pills. It took at least a year… the side effects were debilitating…and it didn’t even cure most people. But as of this year, 2014, everything has changed.

“The era that we have been waiting for has finally arrived. And that era is of safe and highly effective, curative therapies for hepatitis C.”

What’s looking like a safe, reliable treatment for hepatitis C could, theoretically, cure everyone who’s infected. Eliminate hepatitis C.

What’s the hold up? Well, to eliminate something, first you have to know where to find it.

Lynn Taylor, MD knows where to look.

She’s an infectious disease doctor in Providence. After years of treating patients with HIV she came to the conclusion that hepatitis C was causing just as much suffering but not getting nearly enough attention. So she’s made it her mission to change that, starting with Rhode Island. A first step, she says, is catching the disease earlier. And that means getting more people screened, even if they don’t feel sick.

“One of the cruel difficulties with hep c is we don’t know when we catch it, we don’t feel anything typically when we catch it.”

How could that happen? An accidental needle stick, a blood transfusion before 1992, sharing a straw to snort drugs or a needle to inject them. Even once.

“Hepatitis C is a virus that enters the human host through blood only. Not through sexual bodily fluids, not through sweat, not through tears, not through saliva.”

And it doesn’t take much blood.

“We’re talking microscopic amounts of blood, because a trillion viruses a day are made in the human host with hepatitis C. So a tiny spot of blood is teeming with hep C viruses in someone with hep C. you don’t have to see the blood. It’s all microscopic, invisible to the naked eye.”

Once hepatitis C enters the blood stream, it heads for the liver.

“And that’s the cell in the body where the virus replicates.

It churns out baby viruses. And the battle begins.

“There’s a battle between the human being who just got infected and the immune system.”

Like when the body fights off the flu. But with Hepatitis C, most people – about 85 percent—lose that fight.

“…and go on to develop chronic hepatitis C virus infection, meaning the virus stays in the liver cells, it reproduces.”

And slowly attacks the liver. 20 years could pass before you notice anything. But the liver, once mushy and flush with blood, bears the battle scars. The scarring can get so bad it encases the liver, chokes it. That’s called cirrhosis. You don’t want cirrhosis. The symptoms are awful.

“…. swollen ankles and swollen thighs…. slow leaking of blood. People can start to bleed internally…the chemicals build up in the body, they bathe the brain…about 5 % of people per year will go on to develop liver cancer….”

That’s what could happen – with no treatment. But it’s mostly preventable.

There’s an alphabet soup of infectious liver diseases. There’s hepatitis C, but there’s also A and B, and even d and e. No need to worry about most of them. Vaccines exist for A and B. And D and E are rare in the U.S. And while there’s no vaccine for hepatitis C, there is a cure. Maybe you’ve heard the news….

Last year, the only option for most people with hepatitis C was a drug called interferon. Few people could actually tolerate it, the side effects were so bad. The cure rates were pretty low. But in December 2013, Drug maker Gilead Sciences unveiled its first breakthrough hepatitis C drug - Sovaldi. It still had some drawbacks, but it was better than interferon alone. Now, Gilead has just won FDA approval for a drug called Harvoni. It’s one pill, no injections, and the company says most patients can be cured in 12 weeks.

For anyone who tried and failed on the old regimen, these drugs are game changers.

But here’s the catch: the drug carries a thousand-dollar-a-pill price tag, putting it out of reach for many.

Which brings us back to this crossroads.

Infectious disease doctor Lynn Taylor says because hepatitis C takes 20 or 30 years to cause noticeable symptoms, and that’s about how long ago most people with hepatitis C got infected, a wave of very sick people is about to crash.

“And although it’s scary to look at this tidal wave of cirrhosis and end stage liver disease and liver cancer ahead of us, it’s a phenomenal and very unique opportunity in US history, in the global history, to say, you know what, we see this ahead, let’s come together now, let’s do something now.

Let’s get proactive, she says. Test more people. Catch the disease earlier, before it destroys livers.

“We don’t just have to stand here and watch it happen.”

And there is some movement. The CDC recently launched a campaign to get more baby boomers tested.

But concerns are growing that a younger generation struggling with addiction and injecting drugs is quickly becoming the next wave.

Image credit: Jake Harper/RIPR.

This story was originally published by Rhode Island Public Radio.