At The Crossroads, Part 2: Finding hep C infections before it's too late

Reaching out to injection drug users to offer hepatitis C testing could help stop the spread of new infections. But most of the millions of Americans who have chronic hepatitis C aren’t coming to methadone clinics. Most don’t know they’re infected. To help find them, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched a nationwide public education campaign. But is it enough?

Kristin Gourlay reported this story as a fellow in the 2014 National Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. Additional parts of this series include:

At The Crossroads, Part 1: A tale of two epidemics

At The Crossroads, Part 3: As old hepatitis C treatment fades out, new treatments stoke hope

At The Crossroads, Part 4: New hep C drugs promise a cure, for a big price

Hepatitis C infects an estimated five million Americans, nearly 20-thousand Rhode Islanders among them. And most of them don’t know it. But many are about to find out. It takes about 20 years for most people to notice any symptoms from hepatitis C, and it was about that long ago most people got infected. Now doctors in Rhode Island and throughout the country are noticing a wave of patients with the kind of advanced liver disease hepatitis C can cause.

As part of our series “At the Crossroads: Hepatitis C On The Rise And The Fight To Stop It,” we check in on the race to find infections before it’s too late.

------------

How do you stop an epidemic? Keep the people who are sick from infecting more people. Isolate them if you have to, treat them, and cure them. Epidemic over.

But what if you don’t know who’s sick? What if the person who’s still infectious doesn’t know it either, and probably won’t notice any symptoms for decades?

That’s what has happened with hepatitis C. This virus slowly attacks the liver. It’s often 20 years or more before someone who’s infected notices anything wrong. Meanwhile, the infection scars the liver. And that could lead to cirrhosis or even liver cancer. Most of the estimated five million Americans who have chronic hepatitis C are somewhere on this spectrum of sickness right now.

But let’s go back.

Before the scarring, before the story’s final chapters. To where the story began, for one person.

It’s the mid-1980s, Brooklyn, New York. Steve is a healthy young man, a body builder.

“I didn’t use drugs. I didn’t drink. At one time I was studying to be a personal trainer.”

Then one night, something terrible happens.

“I was about 22. I had been jumped coming home from a party one weekend. And I had gotten stabbed and the knife punctured my lung.”

I’m not using Steve’s last name to protect his identity. But picture a big, tall guy. Baseball cap, neatly trimmed beard. He’s soft spoken. Thoughtful. And here’s what he says happens next. He has surgery, needs a blood transfusion. He gets hooked on the prescription painkillers doctors prescribe. Then someone introduces him to something similar, only cheaper and easier to get: heroin.

“And the same person taught me to use a needle and I went to the needle and that’s where I stayed.”

For years, he says. Trapped in this cycle of addiction.

“I would shoplift to get money to buy my drugs. That was the cycle. I would use ‘til I got caught, go to jail, get out, and start the thing all over again.”

Fast forward years later. On one of those trips to jail, Steve tests positive for hepatitis C. He isn’t sure how he got it. He says he never shared needles – that’s one of the most common ways of transmitting hepatitis C. But he could have been exposed in lots of other ways – maybe the blood transfusion, maybe handling someone else’s drug paraphernalia, with a microscopic amount of infected blood on it.

However he got it, Steve has been living with hepatitis C for decades, just like millions of other Americans. Unlike them, he’s known about it for a while. But he says he didn’t want to go through the old treatment for it – using a drug called interferon – because of the horrible side effects.

“Like one of my friends compared it to like chemotherapy or having cancer or whatever. He would get so sick. He’d get his shot every week. You’d know what day of the week it was because he’d get so sick.”

Doctors told Steve his liver was still in pretty good shape, anyway, so he just ignored the hepatitis C. And kept injecting drugs. Until about 2008.

“I decided that I didn’t want to go back to jail, and I didn’t want to use drugs anymore, because I was sick and tired of throwing my life away.”

To help him stay away from heroin, Steve started coming to a methadone clinic. Methadone is a medication that helps opioid addicts ease off of heroin and other drugs.

Clinics like this one – called CODAC, in Providence – treat a lot of former injection drug users. Injecting drugs is the most common way to spread hepatitis C. So that makes this the perfect place to screen people for it.

“We do testing on every single patient in our clinic on admission and then if they’re negative we do it annually.”

This is Diane Plante. She’s a nurse at CODAC.

“Our population now is probably 35 to 40 percent infected or exposed to hep c.”

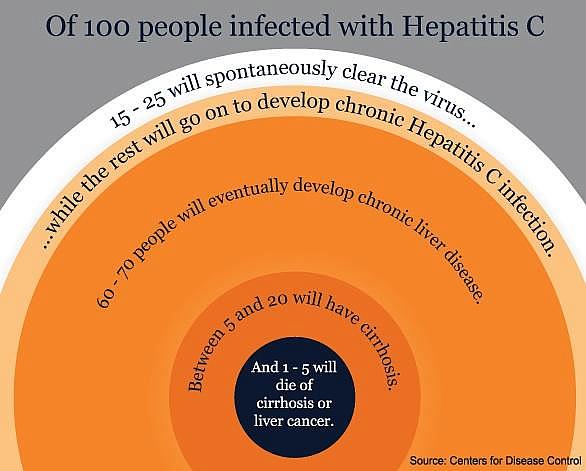

That’s thirty to forty times the national rate. And by the way, when Plante says 35 to 40 percent “infected or exposed,” here’s what she means. A small percentage of people who are exposed to the hepatitis C virus will simply get rid of it on their own, with no treatment. The rest go on to develop chronic hepatitis C, which means the infection doesn’t go away.

Reaching out to injection drug users to offer hepatitis C testing could help stop the spread of new infections. But most of the millions of Americans who have chronic hepatitis C aren’t coming to methadone clinics. Most don’t know they’re infected. To help find them, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched a nationwide public education campaign.

The CDC started recommending hepatitis C screening for anyone born between 1945 and 1965. This cohort accounts for about 75 percent of chronic hepatitis C infections. And screening everyone in a particular age group is much more efficient, epidemiologists say, than asking people to remember something that might have put them at risk decades ago.

That’s what the CDC recommends. But is it enough?

Connecticut and New York state lawmakers don’t think so. Each state has just passed a law requiring primary care doctors to offer hepatitis C screening to patients born between 1945 and 1965. Massachusetts lawmakers are also mulling over a similar law. In Rhode Island, lawmakers haven’t considered any such legislation.

It’s a bit too early to tell if the CDC’s campaign is working, or if the new state laws are having an impact. But if they do, a new challenge emerges: treating all those new patients.

Image credit: Jake Harper/RIPR.

This story was originally published by Rhode Island Public Radio.