At The Crossroads, Part 3: As old hepatitis C treatment fades out, new treatments stoke hope

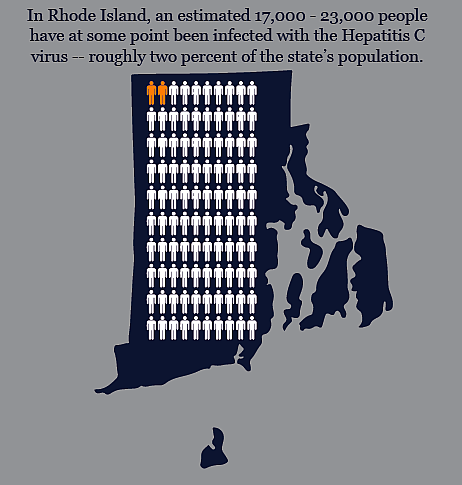

In just a few weeks, another pharmaceutical company will likely win FDA approval for a new drug to cure hepatitis C. That makes three breakthrough medications hitting the market in less than a year. It’s big news for the estimated twenty thousand Rhode Islanders – and many more throughout New England - living with chronic hepatitis C. Some have been waiting decades for a cure. Meanwhile, some patients, such as 62-year-old Jim, have postponed treatment for years.

Kristin Gourlay reported this story as a fellow in the 2014 National Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. Additional parts to this series can be found here:

At The Crossroads, Part 1: A tale of two epidemics

At the Crossroads, Part 2: Finding hep C infections before it's too late

At The Crossroads, Part 4: New hep C drugs promise a cure, for a big price

Source: Brandon Marshall, Brown University School of Public Health and RI Defeats Hep C. Credit Jake Harper / RIPR

In just a few weeks, another pharmaceutical company will likely win FDA approval for a new drug to cure hepatitis C. That makes three breakthrough medications hitting the market in less than a year. It’s big news for the estimated twenty thousand Rhode Islanders – and many more throughout New England - living with chronic hepatitis C. Because some have been waiting decades for a cure.

Next in our series “At The Crossroads: The Rise of Hepatitis C and the Fight to Stop it,” why one man waited so long for treatment.

If you saw Jim on the street or in the supermarket, you’d never guess the journey he’s been on.

“I’ve been in the health care field for over 40 years.

He’s tall, well-dressed….

“I’m 62 years old. White male,” Jim said with a smile.

From Waltham, Massachusetts, right outside of Boston. He’s married. Kids. Grandkids. A job he loves. But things weren’t always so good for Jim. He doesn’t want me to use his last name because his past might cause problems at work.

“I can remember sharing needles. Taking a needle and scratching it on a matchbook to sharpen it. I mean I look back, today, looking back at that it seems like it didn’t happen. It was a bad dream.”

But it wasn’t a dream.

“It was the 60s, things were happening. That’s why I went in the military. My father gave me a couple of choices: go to school, go to the military, or get out.

The other option was jail. Because Jim was doing drugs, stealing cars. So he enlisted. Right during the height of the Vietnam war.

“When I got out of the military and came home, it was 1971, all my friends were coming home. Well, some of them died in Vietnam. Some of them came home and they were in pieces.”

Wounded. Physically. Mentally.

“And they were addicted to heroin from being over there. And other people, there was still a culture, there were a lot of drugs around. And I started shooting drugs again.”

Jim says after the war, they were lost. Jobs were scarce. But drugs were everywhere. He and his friends collected unemployment and got high, sharing needles to shoot heroin and speed.

Decades later, with a family, a career, the drugs and other battles behind him, Jim went to a routine doctor’s appointment.

“I think it was during a blood test that he noticed something.”

The doctor told him he had hepatitis C. He’d had it for decades, most likely from sharing needles with someone else who was infected. Jim’s doctor wanted him to start treatment. But Jim said no. Every year his doctor would say, let’s take care of this. Because hepatitis C slowly attacks the liver. It takes decades, but it can kill you. And Jim, like many baby boomers who contracted the infection in their early 20s, was due for trouble.

“And he kept talking to me about it, you know, we need to think about this. And I kept saying, well, I’ll tell you what, until you get a treatment that can cure me, I’m not going to deal with all this stuff. So I resisted. For years.”

“All this stuff” was a regimen of weekly injections of a drug called interferon. It was the only treatment available at the time for hepatitis C. And it didn’t work for most patients. Not to mention the side effects.

“If you point to any part of the body I can tell you a potential adverse reaction from interferon,” said Dr. Lynn Taylor. She treats patients with hepatitis C in Providence. For years, she’s watched them suffer through interferon.

“Because it’s getting your whole immune system revved up in the hopes it will attack this virus.”

Interferon mimics the body’s natural defense system. Doctors use it to stop viruses and even cancerous tumors. But pharmaceutically speaking, it’s like a bull in a china shop. It might stomp out a virus. But in the process break something important. As Taylor says, point to any part of the body and she can tell you about a side effect. So point to the head.

“Depression with suicidality. … It can cause homicidality, anxiety. I’ve seen the most gentle, calm people who’ve never hurt a fly become angry, kick their dog, have road rage.”

That’s on top of the nausea, sleeplessness, hair loss, weak appetite, weight loss, rashes. The worst flu imaginable, for days after every injection. Three times a week, then once a week, an injection in the stomach. Endless visits to the doctor’s office to draw blood, check levels. A second medication – just as toxic – to boost the effects of the interferon. All this, says Taylor, if you were even eligible to take interferon.

“If you had unstable depression, if you had bad thyroid disease, if your diabetes was out of control, if your blood pressure was out of control, if your vision was going, there’s a whole long list of things that interferon could exacerbate.

Taylor says she hopes she never has to use interferon again in patients. She probably won’t have to because of all the new options.

But Jim didn’t have those options a few years ago, when he was doing this dance with his doctor. His doctor would urge him to start treatment. Jim would push back. Understandable – given interferon’s side effects. But then something happened to change Jim’s mind.

“I saw in the paper one of my friends died. So, him and I grew up together, we were good friends. And I went out to Waltham, and I went to the wake. And I had an opportunity to speak to his sister who I knew years ago. She recognized me right away. And said, ah, jim I’m so glad you’re here. You and him were real good. And I said, what’s up, what happened with him? And she was telling me, well, he did this, he did that, he lived in the western part of the state. But he died because he had hepatitis C. Now he was one of the guys I used to shoot drugs with. Him and I would sit up at night, take the needles, and scratch them on the matchbook. And that kind of opened my eyes.”

The scene shook Jim up.

“Seeing this guy in a casket, and looking at him, and saying, you know, this is like, him and I were very good friends. We were in the marines together. And seeing him dead, and he’s in his 50s. And then just talking to some of the other people. And then just going through the list of people, we all grew up together. Well hey, where’s this one, where’s that one? Of he’s dead, he’s dead. What did he die of? Two or three of them were hepatitis C.”

That’s when he told his doctor he was ready to start treatment. He learned to give himself the injections. And for six months he planned his work schedule, his meetings, his life, around the side effects.

“It made me sick, it made me feel like I had the flu. I felt lethargic. It was hard to get up in the morning.”

Hard to get up at all.

“When I’d come home from work I’d just go right to bed. Weekends I’d just spend most of my time in bed. Fortunately we had a cat, a big black cat. I know it sounds mushy but I tell you what, I was laying in the bed, and I couldn’t even move some days I just felt so sick. And the cat would come up and make me feel better.”

For Jim, the ordeal was worth it. He’s free of the virus now. But the odds were against him. By some measures, fewer than half of patients who try interferon get cured.

“I’m very lucky. I’m a lucky guy. I’ve got good people. My wife’s good. My children are good. I have grandchildren now. Everything’s good. Things are good. Now if I could only get my daughter to move out.”

His daughter aside… not everyone with hepatitis C has been as lucky as Jim. For many patients, it just didn’t work. Others couldn’t tolerate it. They’ve been waiting a long time for this very moment: new drugs, called “direct acting antivirals” have just been approved. So far, it looks like they work much better than interferon, with hardly any side effects. Cure rates of more than 90 percent have been reported. The rub? They’re so expensive many patients aren’t able to access them. Yet.

Coming up next on “At the Crossroads”: Finally a safe, effective cure for hepatitis C, if you can afford it.

Image credit: Jake Harper/RIPR.

This story was originally published by Rhode Island Public Radio.