Dark secrets of Florida juvenile justice: ‘honey-bun hits,’ illicit sex, cover-ups

This article and others in this series were produced as part of a project for the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship, in conjunction with the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

In this photo illustration, a hallway of cells is shown at the Palm Beach Youth Academy in West Palm Beach. (Photo by Emily Michot/The Miami Herald)

By Carol Marbin Miller and Audra D.S. Burch

The boys had just returned to Module 9 of the Miami juvenile lockup from the dining hall when one of them hit Elord Revolte high and hard. More of the boys jumped in, punching and slamming him over and over, then pile-driving his 135-pound body.

One called it an “A-town Stomp,” and demonstrated to detectives by jumping on the floor with both feet.

Elord, 17, fought back gamely. “I swung a punch,” said the youth who struck him with the first blow. “I hit him. He swung two punches. He hit me. I swung one punch and then I grabbed his shirt and hit him again. Then I slammed him on his head and I hit him. ... All my friends, they start jumping over the chairs, while Elord was on the floor and they went to stomping on him.”

Thirty hours later, Elord was the one dead, the result of internal bleeding from that mauling, which two of the youths said was instigated by a detention officer.

Elord Revolte’s death evokes many of the dark secrets of Florida’s troubled juvenile justice system, including incompetent supervision, questionable healthcare, willfully blind internal investigations and spasms of staff-induced violence, sometimes bought for the price of a pastry.

The lack of accountability has left children in peril, unfit employees in charge and parents frustrated, frightened and sometimes grieving.

“They treated my child worse than a dog,” said Enoch Revolte, Elord’s father. “My child wasn’t a dog. My son deserves justice.”

He didn’t get it. No one was held to account.

Not the dozen-plus boys who ambushed Elord.

Not the detention officer identified by a detainee as ordering up the attack because Elord had mouthed off minutes earlier.

Not the nurses who waited a day to get Elord to the hospital as he oozed blood internally.

Not the administrators who failed, despite repeated warnings, to supply juvenile lockups with modern surveillance equipment.

Spurred by the death of Elord Revolte on Aug. 31, 2015, at least the 12th questionable juvenile detainee death since 2000, the Miami Herald embarked on a sweeping investigation of juvenile justice in Florida.

Reporters examined both state-run juvenile detention centers, essentially jails for kids ages 13 to 18 who are accused of crimes, as well as the state’s residential “programs,” prison-like institutions where they are sent by judges to serve sentences and receive treatment. The latter are privately run, but funded and overseen by the state.

Herald journalists examined 10 years of Department of Juvenile Justice incident reports, inspector general investigations and administrative reviews, restraint records, police files and court cases, state inspections, child welfare and prison records, emails, personnel files, surveillance video and handwritten witness and victims’ statements. They conducted scores of interviews with administrators, public defenders, prosecutors, judges, children’s advocates, consultants, parents and youths across Florida. They toured a half-dozen programs in two states and observed juvenile court cases.

The investigation found that for years — long before Elord’s death — youths have complained of staff turning them into hired mercenaries, offering honey buns and other rewards to rough up fellow detainees. It is a way for employees to exert control without risking their livelihoods by personally resorting to violence. Criminal charges are rare.

Of the 12 questionable deaths since 2000, including an asphyxiation, a violent takedown by staff, a hanging, a youth-on-youth beating and untreated illnesses or injuries, none has resulted in an employee serving a day in prison.

DJJ Secretary Christina K. Daly said her agency does not tolerate the mistreatment of youth in its care. “The Florida Department of Juvenile Justice has been and continues to be committed to reform of the juvenile justice system in Florida. We have worked over the past six years to ensure that youths receive the right services in the right place and that our programs and facilities are nurturing and safe for the youths placed in our custody,” she said.

True culture change 'takes time'

DJJ Secretary Christina K. Daly talks about weeding out staffers who are not on board with the department's reform efforts.

The Miami-Dade lockup culture of violent retribution could spill out into open court when a teenager faces trial for a murder committed on a Liberty City street corner. The victim’s mother says he was groomed by staff at the lockup to beat people up. The alleged shooter was the recipient of one of those beatings a little over a year earlier.

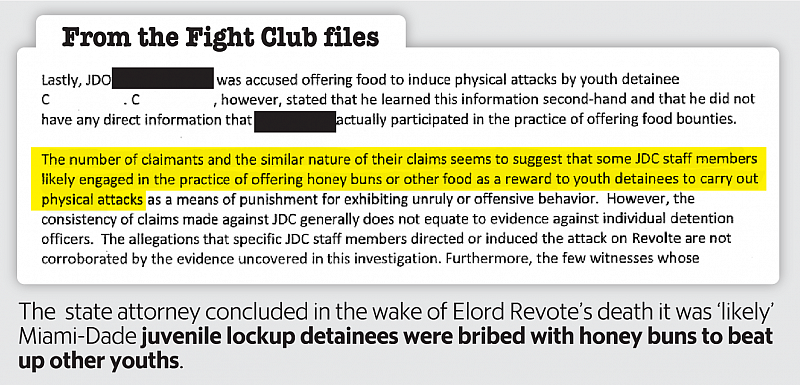

After Elord’s death, Miami-Dade criminal prosecutors and the state attorney’s anti-corruption unit began a probe in response to a Miami Herald investigative report on the incident. In the Herald article, the public defender’s chief assistant for the juvenile division, Marie Osborne, said detainees are turned into enforcers by outnumbered staff, and that “in here, a honey bun is like a million dollars.”

Though they did not file criminal charges, prosecutors concluded that detention officers “likely engaged in the practice of offering honey buns or other food as a reward to youth detainees to carry out physical attacks as a means of punishment for exhibiting unruly or offensive behavior.” Still, prosecutors concluded that the allegation that an officer instigated the beating that killed Elord Revolte was “not corroborated by the evidence uncovered in this investigation.”

The Department of Juvenile Justice undertook its own inquiry into “honey-bunning” after the Herald report. Despite several witnesses telling investigators that the lockup staff instigates fights by offering rewards, the inspector general concluded that there was insufficient evidence to prove or refute the allegation.

If brutality-by-proxy is a symptom of what plagues juvenile justice in Florida, these are some of the causes:

▪ Low pay and inexperienced staff: The state offers starting detention officers $12.25 an hour to protect and supervise youths often dealing with mental illnesses, drug addiction, disabilities and the lingering effects of trauma. That’s $25,479.22 a year for a new recruit. The Legislature hasn’t seen fit to raise the starting pay since 2006 — although it did give current staff a $1,400 raise on Oct. 1.

Starting salaries remained the same.

When the state handed over its residential programs to private contractors, it abdicated its say over the pay for those employees, unless stipulated in the contract. TrueCore Behavioral Solutions — which operates 28 Florida programs, more than any other company — offers new hires $19,760.

Some states insist on college degrees from prospective employees. Florida does not. Workers fired for wrongdoing in recent years have included a former brick mason, furniture salesman, mail sorter, sales rep, a machinist and a boxer.

Many staffers share one trait: intimidating bulk.

▪ Inadequate personnel screening and standards: Having a violent or sexually abusive past has been no bar to employment with the Department of Juvenile Justice and the private agencies that operate Florida’s residential compounds for kids. At least not until recently, when the Herald began requesting personnel records and the department promptly wrote an internal memo issuing stricter guidelines.

Hundreds of washed-up prison guards have been hired, including individuals who lost their jobs for sexually abusive treatment of colleagues, “improper relationships” with inmates, smuggling in contraband and sleeping on the job.

The results can be predictable. One caregiver pleaded guilty to knocking out a disabled man in a group home, was convicted and still on probation when he signed on with a youth program in Jacksonville. Five months later, he violently clubbed a 15-year-old with a flashlight.

A worker at a prison psychiatric hospital, ousted because of an “inappropriate relationship” with an inmate, joined the staff of a youth program, and within months was accused of having sex with a detainee on the bathroom floor.

DJJ records are peppered with allegations of staff engaging in sex with detainees. One counselor at a Fort Lauderdale program — she was known as “the cradle robber,” a public defender wrote — bore the child of a recent detainee. Six months later, the program gave her a glowing recommendation for a job working with kids.

▪ Tolerance for cover-ups: Over the past 10 years, DJJ has investigated 1,455 allegations of youth officers or other staffers failing to report abusive treatment of detainees — or, if they did report an incident, lying about the circumstances. That’s nearly three times a week.

In August, the Polk County Sheriff’s Office charged three former top administrators of the Highlands Youth Academy with evidence tampering. Sheriff Grady Judd said the managers covered up widespread sexual misconduct by destroying written statements, and concealed an attack on a detainee by hiding incriminating video.

Judd said the academy’s bosses “weren’t reporting what was occurring to DJJ, and DJJ was ignoring the obvious. They ignored it all.”

▪ Faulty security cameras: Going back at least 15 years, administrators have been told repeatedly and emphatically that aging, faulty video cameras undermine the state’s ability to investigate wrongdoing. And that the systems are easy to circumvent.

A 2015 investigation into claims that a teen was knocked out in the shower after a worker “set him up to be jumped” was stymied when the agency discovered that a combined 135 seconds of video had vanished — from two separate cameras. One video in another case shows a detainee standing on a chair and swinging the camera lens sideways in preparation for a beating reportedly encouraged by a staffer.

A youthful detainee turns a camera lens to the side shortly before a beating was administered in a classroom at the Palm Beach Juvenile Correctional Facility. Youths told investigators the fight was arranged by staff.

Elord Revolte’s case was only the latest in which security cameras played a critical role.

▪ Legal impunity for abusive staffers: After a teen died from a head injury when a West Palm Beach staffer dropped him on his skull, lawmakers passed a 2014 law that made it easier to punish abusive or neglectful youth workers. The Florida Department of Law Enforcement could cite no instance of it ever being invoked until this August, when the three former administrators were charged at Highlands.

If harsh treatment is meant to deter youths from re-offending, it doesn’t seem to be working. The state says 45 percent of all detainees wind up back in the justice system within one year, many as adult offenders. Although no precise tracking data could be found, it is clear that Florida’s juvenile justice programs have become an on-ramp for the adult prison system.

Mark Steward, who was director of the Missouri Division of Youth Services for more than 17 years and is credited with turning it into a national model, said: “Everybody should feel shame for letting this happen. Everybody. Legislators, the governor, the people running these programs.”

For years, “honey-bunnings” and other abuses have been as ubiquitous as razor wire and starchy vegetables.

Broward County’s top juvenile public defender, Gordon Weekes, said his office has complained repeatedly that poorly nourished youths were being manipulated by staff. DJJ could lessen the problem, he said, by removing vending machines from employee lounges and strictly enforcing the prohibition on outside food.

“They have the evidence. They have the complaints. They have a pattern of incidents all throughout Florida,” Weekes said.

“It’s barbaric.”

Thousands of juvenile justice officers and youth workers oversee unruly and sometimes violent teens across Florida every day. Most of them follow the rules, treat the detainees with kindness and decency, and provide the necessary guidance and mentoring. Their jobs, in addition to offering low pay, carry significant risk. When officers fall short of their obligations, though, the consequences for detainees can be far-reaching.

“We can have the best policies, procedures, practice, vetting — you name it. There will always be someone who makes a poor decision,” said DJJ’s Daly. “It’s very hard to prevent that from happening, but it is my expectation of myself and this agency that we do everything we can do to make sure we’ve got the right practices, policies and procedures in place to avoid that from happening.

Christina K. Daly, Secretary of the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice, gives a tour of the Miami-Dade Regional Juvenile Detention Center. Emily Michot

“We have thousands of dedicated employees and, unfortunately, there have been some that have come into our system that have caused us great heartache and frustration,” Daly said. “It always comes down to one person’s judgment.”

ADULT ADVICE AND A PUNCH IN THE NOSE

The video is blurry, as if you’re watching it through gauze — and you are, in a sense, as state juvenile justice administrators have fuzzed up the images to conceal identities before releasing the footage in response to a public records request.

Andrew Ostrovsky is backpedaling into the center of the frame. A dark-clad detention officer advances. He grabs skinny 14-year-old Andrew by his shirt and thrusts him into a wall of the Broward Regional Juvenile Detention Center cafeteria. Andrew remains pinned to the wall for about seven seconds, officer Darell Bryant holding him there.

Suddenly, Bryant clutches the boy’s arm like a handle and tosses him onto his back. As Andrew lies on his back, Bryant punches his face, breaking his nose in two places.

DJJ staffer body-slams, slugs a skinny 14-year-old

Andrew Ostrovsky went for a drive in his father's car without permission. A detention officer at the Broward lockup beat him up and broke his nose. The kid was locked up. The grown-up went home.

“Wow, wow, wow....”

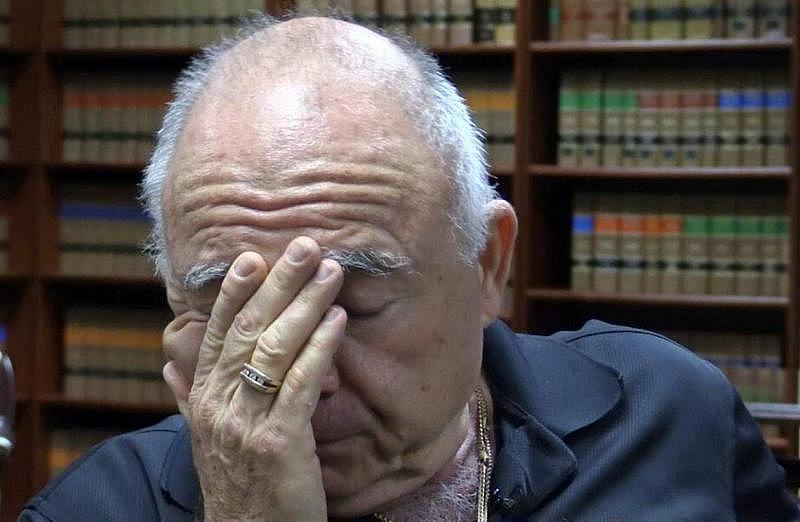

Andrew’s incredulous father, Uri Ostrovsky, is watching the video for the first time. “He needs to go to jail.”

“What a son of a bitch,” Ostrovsky says, softly, as he asks to watch the Feb. 12, 2017, beating a second time.

Like many youths in the system, Andrew has lived a difficult life. Ostrovsky adopted his son from foster care in Maine. Andrew had been removed from his mother’s care at 18 months, adopted by another family at 3, and then returned at age 6 like an ill-fitting sweater, abandoned back to the state in a parking lot, Ostrovsky said. “They told him, ‘We don’t want you any more.’ ”

“He suffered in his life,” Ostrovsky said. “He doesn’t trust.” Still, his father said, Andrew never took his pain out on other children. “He is not a strong kid, and he’s not aggressive. He never beat up anybody.”

Uri Ostrovsky gets emotional as he watches surveillance footage of his 14-year-old son being beaten by a guard. ‘He needs to go to jail,’ Ostrovsky says of the guard, who resigned. The criminal case remains open. Emily Michot

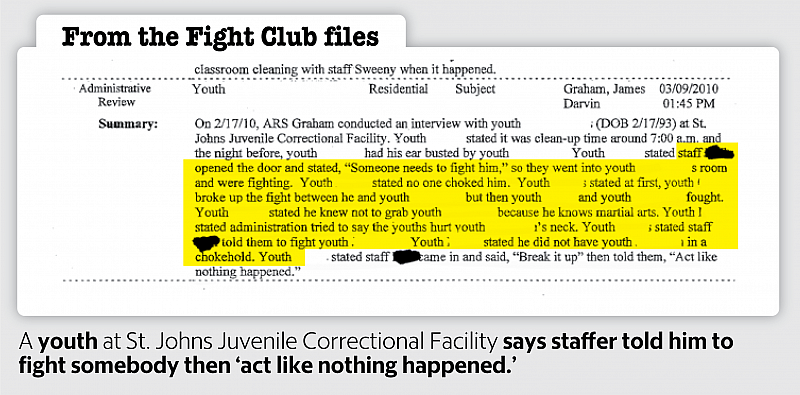

Andrew was in the detention center for joyriding in his father’s Dodge van. The DJJ report says Andrew complained to a staffer that he was having a hard time with another youth. So hit him, Andrew said the staffer replied.

“The guard told my son to beat up another kid there,” Ostrovsky said.

“That’s when the guard broke his nose,” Ostrovsky said. After the punch, a report said, Andrew was “hyperventilating and large amounts of blood [were] trailing from the dining hall.”

After visiting his son at the hospital, Ostrovsky said he confronted the lockup superintendent, who told him officers “don’t get paid well, and nobody wants the job.”

The DJJ investigation quoted Andrew as saying the other boy had been “talking junk to him,” and he sought advice from Bryant. “Bryant told him to hit [the other] youth when no one is looking in the dining hall.” The report implies, and video seems to show, that Andrew did just that — throwing a feeble jab — and that the staffer violently intervened to break up the confrontation. At the moment Andrew is thrown to the ground, he is in full retreat.

Notably, the 10-page report never resolved Andrew’s allegation that an officer instructed him to hit another youth.

Bryant “resigned in lieu of termination,” a DJJ spokeswoman said. Fort Lauderdale police detectives forwarded their findings to the Broward State Attorney’s Office, and the case remains open, a spokesman said. The Herald was unsuccessful in reaching Bryant.

Ostrovsky ponders the odd calculus of crime and punishment, children and adults: His 14-year-old was jailed for a nonviolent act and then beaten bloody. The attacker, an adult, remains free. Andrew, his father said, “did bad stuff. He paid for it. It doesn’t mean that you have to break him.”

PANHANDLE PURGATORY

Florida’s youth corrections system has been a source of shame and scandal since its inception. The Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys, the state’s first reform school, was opened in the Panhandle in 1900 as a reform-minded experiment in “intellectual and moral training.” Three years later, boys were found chained in irons.

The 'White House Boys': a Florida horror story

The "White House Boys" were youths — now mature men — who endured horrible abuse at the Dozier reform school, Florida's first juvenile justice institution. Decades later, the state apologized.

The state has been the subject of blistering grand jury reports, defended countless lawsuits, ramped up and slashed funding, designed and redesigned new programs — only to see the same abuses recur.

Despite the periodic outrages, those in the juvenile justice system have never gotten the same attention as abused and neglected children — although they are, in many cases, the same children, simply grown older and more damaged.

TrueCore, the private contractor, has researched its detainee population. It said incarcerated girls are four times more likely than their non-delinquent peers — and boys three-and-a-half times more likely — to have experienced traumas such as abuse and neglect.

For generations, Florida juvenile justice programs were interwoven with the state’s child welfare system in a mammoth department called Health and Rehabilitative Services. The agency operated under a social services model, with foster care and delinquency programs governed by a child’s best interests. That philosophy remained in place even after delinquency programs were spun off in 1994.

But in 2000, the agency turned toward punishment when the Legislature approved an overhaul called “Tough Love.” As Florida grappled with a surge in violent youthful crime, a wave that jeopardized the state’s tourism lifeblood, the emphasis was on “tough.”

“We stopped seeing young people as somebody’s child, but rather as predators to be feared. And the way you deal with a predator is the opposite of how you deal with a child who has made a poor decision,” said Jim DeBeaugrine, an HRS legislative analyst from 1988 to 1997, and then staff director for the state Justice Appropriations Committee until 2007.

The 2000s saw two dramatic shifts: From 2008 until this year, the number of juveniles who entered the system’s custodial care plummeted from 41,002 to 19,491. The reduction coincided with a nationwide drop in youth crime, along with a 2011 Florida law — championed by DJJ — that encouraged police to issue civil citations to some nonviolent youthful offenders instead of arresting them.

At the same time, the Legislature privatized all juvenile justice commitment programs — the brick-and-mortar facilities where youths serve out their sentences. Daly, the DJJ secretary, says this outsourcing has led to greater efficiency and accountability, and more humane conditions.

A 2015 Polk County grand jury report following a riot at Highlands Youth Academy — named Avon Park at the time — saw it differently.

The riot started over a bet on a basketball game. The stakes: a packet of Lipton Cup-a-Soup. The losers refused to pay. Approximately 150 law enforcement officers were deployed, including a SWAT team. Sixty-one juveniles were arrested.

After examining the uprising at the program for boys with mental illnesses or drug addictions, the grand jury labeled it “disgraceful.”

“The buildings are in disrepair and not secured, the juvenile delinquents are improperly supervised and receive no meaningful tools to not re-offend, the staff is woefully undertrained and ill-equipped to handle the juveniles in their charge, and the safety of the public is at risk,” the report said.

The grand jurors noted that boys were running wild, living in buildings with leaky roofs — one still had a blue tarp — because they were never repaired after Hurricane Wilma a decade earlier. The report pointed out that British-based G4S, the for-profit company then running the youth program, had been paid $40 million over five years, including a 9 percent profit margin, or about $800,000 in profit that year alone, to run the camp.

“While the citizens are essentially being ripped off,” the report said, “the juveniles are being even more poorly served.”

G4S was sent detailed information about what the Herald was preparing to publish in this report. The company, which has spun off its juvenile contracts to TrueCore, a firm run by former employees, did not respond.

Three Highlands Youth Academy administrators arrested for running abusive program

Three former high-level administrators at Highlands Youth Academy have been arrested, charged with running a program steeped in abusive treatment of youths, cover-ups and illicit sex between staff and detainees.

FAST FOOD AND FALSE PROMISES

Amid the downsizing, residential programs like Avon Park/Highlands — and the lockups, where youths await adjudication and sometimes scarce beds in the residential programs — have remained a source of trouble. The trouble ranges from improper “restraints” — forcible takedowns by staff — to ham-handed efforts to prevent detainees from reporting abuse.

Florida's waiting list for specialized programs

DJJ Secretary Christina K. Daly talks about the shortage of beds in programs designed to help youths with drug abuse and other issues. Detainees end up waiting in the lockup for an opening.

Fort Myers Youth Academy has been a microcosm, steeped in violence and a culture of coercive cover-ups. The program was placed under a “corrective action plan” in September 2014 after it was found to be manhandling too many detainees.

Rather than stanch the abuse, the head of Fort Myers, Michael Mathews, went to extreme lengths to prevent it from being reported, DJJ inspector general records show.

Staffers told investigators they were forbidden from reporting anything to the state child abuse hotline without permission of administrators — a violation of DJJ policy, which mandates the reporting of abuse and requires that detainees have access to the hotline. Youths claimed they were pressured or bribed — one youth said with chips — to keep their mouths shut.

In April 2015, a 17-year-old clashed with Davis Rios, a youth care worker hired by Fort Myers after he was allowed to resign from his prison job. He’d initially been fired from the prison position for sexual harassment.

Rios swept the detainee’s legs out from under him, tossing him to the floor, wrote Christopher Geraci, a supervisor who witnessed it. Rios then bent the boy’s fingers backward and twisted his shoulder joint behind his back, “causing him to scream in pain.”

The youth had recently broken his jaw, and it was tender. Rios, exploiting the injury, gnashed an elbow into the teen’s wired jaw, eliciting a howl of pain, records show. The boy was “crying and begging Rios to stop.” The teen said Rios had “tried to break his arm.”

When it was over, the youth had his teeth knocked out of place, and his mouth dripped blood. He was sent to the emergency room with a shoulder injury, “multiple” deep bruises and internal bleeding.

Such “pain compliance” moves, permissible in adult prisons, have been banned by DJJ for more than a decade.

Geraci wrote a three-page report describing how Rios “became physically aggressive,” how he had done a “pain compliance technique on [the] youth’s fingers,” and how he’d twisted the teen’s shoulder, “causing him to scream in pain.” And it said he kept going even after Geraci ordered him to stop.

Mathews demanded a rewrite, Geraci later would tell investigators. The statement went from a three-page narrative to one paragraph devoid of detail. Geraci also refrained from calling the abuse hotline as mandated, later explaining: Staff “are prohibited from doing so.”

Mathews “offered no explanation as to why the Abuse Hotline was not contacted after medical documentation supported [Geraci’s claim] that staff Rios manipulated youth’s shoulder with the intent to inflict pain,” the report said. Nonetheless, a DJJ lawyer concluded that there was “no intent on his part to mislead the department.”

The episode remained buried for three months, until DJJ investigators came to Fort Myers to look into another takedown. Soon, more complaints surfaced, including a kid who suffered a dislodged tooth and possible “roof fracture” when he refused to give up his lunch tray, a youth who claimed he was yanked out of bed and beaten for oversleeping, and a report from a teen of “bounties” being offered for beatings.

On Oct. 23, 2015, an inspector general investigator wrote a report in which detainees described widespread abuse and frequent cover-ups. The program physician, Dr. Hala Fakhre, said she was told administrators dissuaded detainees from reporting physical abuse. A former staff nurse, Kandis Kelting, said she quit because of excessive violence and “youths being called liars.”

One boy said Mathews “bribed him with fast food ... and false promises” — such as a reduced stay — to hide abuse.

“Things tend to get swept under the rug,” Geraci said in an inspector general report.

Those things included the surveillance footage of Rios’ April 2015 “pain compliance” restraint. Mathews didn’t preserve the video, later explaining that he viewed the video himself and saw “no excessive use of force.”

Rios was terminated in November 2015. Mathews was fired the following year — after he failed to report another restraint. Neither could be reached by the Herald.

The totality of complaints resulted in another “corrective action plan,” this one stipulating that the program report abuse “100 percent of the time.”

TURNING A BLIND EYE

For going on 20 years, investigators have been dutifully reporting concerns over the system’s outdated surveillance cameras. In July and August of 2000, two Miami-Dade officers were found to have beaten detainees with a broomstick. One boy was hurt, but in both cases the lockup “failed to ensure the video equipment was operating correctly, which prevented review” of the allegations.

The next year, an investigation into a Pinellas County girl’s injured shoulder was thwarted by inoperable cameras.

On June 9, 2003, 17-year-old Omar Paisley died of a ruptured appendix at the Miami-Dade lockup after begging for help for three days. A grand jury later complained that most of the video cameras weren’t working, and those that did “allowed only for real-time monitoring.”

Investigations into the deaths of two other youths, as well as the rape of a third, also were hamstrung by poor surveillance equipment. Shawn Smith, 13, hanged himself while under suicide watch in Volusia County. Daniel “Danny” Matthews, 17, died after being punched by another Pinellas County detainee. And a severely disabled 16-year-old was placed in the care of a sex offender, a detainee deputized to change his diaper. In that instance, the Tallahassee lockup’s tapes vanished before investigators could view them.

In some programs, the equipment was upgraded — but officers quickly learned the blind spots.

At the Okeechobee Youth Correctional Center, the “sub control” center, a glassed-in enclosure, is not covered by cameras, and the glass is darkly tinted. Police said that is where youth worker Mackell Williams brought a 15-year-old on Aug. 16, 2012, to beat him up.

A witness reported that Williams repeatedly punched the boy, then hoisted him in a “bear hug” and slammed him to the floor on his head. The 15-year-old crumpled and initially remained motionless. A co-worker told investigators she “thought the youth might have broken his neck.”

A detainee suggested that the teen needed medical attention, but workers “refused to notify anyone from medical,” a report said. One staffer dabbed the boy’s bloody head with napkins.

He was, in fact, badly hurt. The teen passed out in a classroom the next day from an apparent seizure and was diagnosed at a hospital with head and neck injuries. He returned to Okeechobee only to lose consciousness three days later — and then suffer another seizure the day after that.

DJJ and child abuse investigators concluded that Williams and two others had medically neglected the boy. They also determined that Williams had physically abused him. He was charged with misdemeanor battery.

Williams, six feet tall and stocky, wrote in a statement that the youth was the aggressor and he was “thrown around” by him while he begged the boy to “please let go.” He was acquitted four months later.

Managing the surveillance cameras throughout the juvenile justice system has long been a struggle, DJJ’s Daly said, forcing administrators to balance security needs against privacy rights. “You want kids to have the privacy in their room; you want them to have the privacy in the bathroom,” she told the Herald. She added that the agency can replace the equipment only as its budget allows.

“We are constantly replacing those cameras and the systems. There are a lot that are outdated, and we just have to prioritize and do them as we can,” Daly said. DJJ bought 135 cameras for its detention centers in June 2015 — along with new hard drives and other equipment — and another 100 security cameras the following May. About one-third of those were installed in Miami. Another 40 wide-angle cameras were installed in Miami later that year.

“It would be inaccurate to say DJJ does not take our facility safety seriously,” Daly said.

Daly on replacing defective cameras: It’s expensive but happening

DJJ Secretary Christina K. Daly says the juvenile justice system is replacing cameras that are out of date and don't adequately deter abuse, including those at the Miami-Dade lockup where Elord Revolte died. The department says those cameras have been upgraded.

ON A SCALE OF 1 TO 10: ‘TWENTY’

The Miami-Dade Regional Juvenile Detention Center cameras were working on the afternoon in 2015 when more than a dozen boys in Module 9 used Elord Revolte as a punching bag. But they weren’t working very well.

The lockup was Elord’s last stop in an odyssey that began at Miami International Airport. He ran away from the airport, fearing that his father was planning to take him to Haiti and leave him there. Elord ended up in a Miami Beach foster home. He ran away from there, too, and had been spotted by other foster kids smoking marijuana in South Beach. His foster mother reported him missing but said authorities didn’t seem interested.

“Nobody really cared,” said Jolie Bogorad.

They did care when, according to police, he and another youth took a man’s cellphone at gunpoint. Elord was arrested Aug. 28, 2015. In general, detainees are sent to the lockup for 21 days to await trial or release, though the time can be extended. Elord lasted three.

Enoch Revolte said he spoke with his son by phone not long before the attack. “He said, ‘Dad, I love you a lot.’

“I told him, ‘If you loved me, you would not be where you are.’ I was trying to practice tough love.”

Those words, among his last to his son, haunt him.

More haunting were the events late in the afternoon on Aug. 30. Elord “stood up without permission” in the lockup cafeteria to get a carton of milk, according to the police report. Detention officer Antwan Johnson told him to sit down. Elord cursed at Johnson, who cut dinnertime short for everyone.

One detainee, 16-year-old L.B., told police he overheard Johnson instruct another boy, T.R., to “punish [Elord] for his misconduct,” prosecutors wrote in a memo that identifies the juveniles only by their initials. “Johnson told the youth, [T.R.], to hit him,” L.B. said.

The boys from Module 9 returned from the dining hall at about 5:33 p.m. Policy dictated that they stand in front of their doors, but they milled around a set of blue plastic chairs in the dayroom, preparing to watch a movie. Video shows two officers present. Johnson is entering a closet. Boris Valcin walks away.

Neither is in position to see what happens next: T.R. slugs Elord in the jaw. Elord’s arms flail in the air.

Valcin continues to walk away when at least a half-dozen detainees leapfrog chairs and converge on Elord. Others join the attack. By the time Valcin turns around, Elord is swallowed by a blur of kicking khaki. Valcin radios a Code Blue, or fight. Johnson enters the scrum and begins to peel off one youth. All told, the assault goes on for 68 seconds.

Detainees at the Miami juvenile lockup jump over chairs to get at Elord Revolte, who is in the upper left-hand portion of this video surveillance image, already engulfed. Miami-Dade State Attorney

“The guards was grabbing them and, like, throwing them,” 16-year-old T.R. told police, “but they kept coming back.”

“Stop!” Elord yelled. As staffers disengaged the remaining attackers, at least one stomped Elord’s chest a final time.

When it was over, Elord rose to his feet and declared: “I’m straight.”

Another detainee, D.V., would support L.B.’s claim that the assault was “induced” by a staffer, and said that the attackers were offered food and extra phone calls as rewards. He said he overheard the boys say so.

Elord was placed on concussion alert, and was supposed to be monitored for “repeated vomiting, dizziness, headache, visual disturbances, seizures, confusion, or unusual drowsiness.” DJJ’s inspector general said those instructions were disregarded. Indeed, “no staff had contact” with Elord for hours.

At 10:19 the next morning, Elord told an officer “his chest was stabbing him and he could not breathe.” A supervisor replied that Elord “already had submitted a sick-call.”

When the same officer checked on him later, Elord was “clutching his chest” and asked to see a nurse. The officer told him to be patient. A nurse said he’d be right over but never arrived.

At 3:40 p.m., shortly after shift change, staff called a Code White — medical emergency — and Elord was taken to the nurse’s station. He said he “felt like something was broken in his chest, and it was hard for him to breathe.” The staff did not call for an ambulance, and it took more than an hour for officers to arrange for a van.

Asked to describe his pain on a scale of 1 to 10, Elord replied: “Twenty.”

5:17 p.m.: Elord is checked in at Jackson Memorial Hospital’s emergency room. He says he has abdominal pain. He vomits.

10:40 p.m.: Elord stands over a garbage can and points toward his throat, unable to breathe. In full cardiac arrest, Elord falls into the arms of a nurse.

11:17 p.m.: Elord is pronounced dead.

The medical examiner catalogued his injuries — some overtly evident, some not. His left eye was bruised and swollen; he had an L-shaped scrape to the right side of his face, several red-brown scrapes and a purple bruise on his neck, and bruises to his shoulder. He bled from his thyroid, trachea, both lungs, adrenal gland, rib area and heart.

A tear to a vein under Elord’s left shoulder — which slowly oozed his lifeblood — was the cause of death, along with other “blunt force injury” to his head, neck and chest. It was “a highly unusual injury ... more associated with a motor vehicle collision than a fight,” prosecutors quoted the medical examiner as saying.

Manner of death: homicide.

The state attorney’s office cast about for someone to charge. Prosecutors considered Johnson, but concluded they couldn’t prove the officer ordered the assault, which he denied.

Nor, they determined, could the youths be prosecuted. Though investigators watched the kicks and punches unfold on the blurry, herky-jerky video, they could not say who delivered the fatal blow. Surveillance equipment was “significantly outdated,” prosecutors wrote. The cameras would need to capture 30 frames per second but recorded only seven.

When technicians tried to zero in, the images muddied. DJJ said it has upgraded the surveillance system.

The state attorney said the lockup’s shoddy record-keeping further complicated matters. The day log is unclear as to how many detainees were in the module. That complicated the task of identifying attackers and witnesses.

T.R. told investigators he punched Elord as payback for an earlier fight, though no such fight had been documented and prosecutors suggested he made that up. Multiple detainees acknowledged jumping in for no particular reason, but they weren’t charged with assault, much less homicide.

After itemizing the lockup’s “inadequacies,” the state attorney’s office concluded they were “beyond the scope of this memorandum, but must surely be addressed.”

In an interview with the Herald, Daly said DJJ has emphasized that detainees can never be deputized to enforce discipline. “I can tell you right now that it is absolutely unacceptable for any of that to happen. I have been very clear with our staff. We’ve had numerous conversations. That is not accepted. It is not an acceptable practice. Period.”

Inexplicably, the state attorney memo closing out the case says Antwan Johnson was terminated for unrelated matters. In fact, he remains on staff.

“These allegations were the subject of investigations by both the Inspector General’s Office of the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice and the Public Corruption Unit of the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office. Neither of these extensive investigations found Mr. Johnson culpable in the incident,” DJJ said in a statement last week.

Reporters attempted directly and through the department to contact Antwan Johnson but did not succeed.

Revolte expressed shock when a reporter told him that no one would be punished for his son’s death.

“What do you mean?” he asked in Creole. “I cannot understand. This cannot happen. This cannot happen.”

T.R., who freely admitted striking the first blow in the savage attack, was soon freed.

MEAN STREETS: A MIAMI EPILOGUE

Because his initial explanation made no sense, the state attorney’s office intended to go back and interview T.R. one last time after his release. They thought he might feel freer to talk without fear of retribution by the detention center staff. But on Oct. 18, 2015, less than two months after Elord’s death, T.R. and a friend were shot while standing outside a Southwest Miami-Dade apartment. T.R. was wounded in the leg. The friend was killed.

Prosecutors decided to let it go.

The Herald learned that the U.S. Justice Department subpoenaed records of some of the detention center staff involved in the incident, including Johnson.

At least one of the detainees present during the fatal beating was called to testify before a grand jury. Progress, if any, in that investigation is unknown.

T.R. is now in a Miami-Dade adult jail, charged with murder.

Police say he shot 31-year-old Alquehen “Sean” Webb Jr., with a Glock .40-caliber handgun on Jan. 10, 2016, as the man sat in a car smoking marijuana.

T.R.’s lawyer, Arthur Wallace, said it is a “weak case” and “there’s a good chance he’s completely innocent.”

T.R. is Tyvontae Robinson. He was never identified by name in the police, prosecutorial or juvenile justice records obtained by the Herald pertaining to the lockup brawl. Only his nickname — his handle in the lockup — was disclosed.

Fellow detainees called him “Honey Smack.”

[This story was originally published by Miami Herald.]