Defeated by drugs, Kentucky man takes his own life

Laura Ungar wrote these stories for The Courier-Journal as a 2012 National Health Journalism Fellow. Other stories in this series include:

Former soccer mom turned addict helping other women

Native spirituality helps some cope

How Lines for Life helps out the addicted 24/7

Oregon's success in treating addicts is a lesson for Kentucky

Recovery Kentucky centers use a supportive program in which the clients hold one another accountable

Treatment options for tackling addiction can vary from hours to months

Waiting-list names haunt woman at The Healing Place in Louisville

Funds for infant withdrawal syndrome are scarce

Tormented by a prescription-drug addiction he couldn’t escape despite treatment, Michael Donta took a final, drastic step — hanging himself in a motel room, leaving behind a baby son and pregnant girlfriend.

“He wanted to get off of (the pills) so bad, but he couldn’t. ... He didn’t see the ability to get any help,” said his father, Mike Donta of Ashland. “I think he would’ve been alive today if he got better treatment.”

Like too many addicted Kentuckians, Michael, who was 24 when he died in 2010, was tripped up by a host of obstacles when he sought help. And when he finally got treatment, it wasn’t enough.

His attempts at sobriety began when he approached his father in late 2008, saying he had a problem. Mike Donta had noticed that his once-outgoing and athletic son was becoming increasingly agitated and having problems paying his bills.

He called a local hospital and put Michael into a seven-day detoxification program. It worked briefly. But before long, colleagues at Michael’s railroad job suspected he was using again, and a union official called his father.

“I promised to get him some help,” said Donta, 53, a deputy commissioner at the Kentucky Labor Cabinet. “Come to find out, everywhere I called is a six-months, eight-months, a year wait.”

He wanted to get his son into a long-term residential recovery center. But the closest was in Morehead, with a 12-month waiting list, an hour from Ashland.

Donta didn’t think his son could wait that long. So the family settled for a 30-day residential program in Elizabethtown, more than three hours from Ashland.

Michael entered the program in the fall of 2009 and did well inside. But within weeks of returning home, he turned back to drugs, his father said.

He began stealing from his father’s home, including a television and lawn mower, to pawn for drug money. Donta pressed charges in 2009, and his son spent two months in jail.

“He just kept going; he couldn’t get off of these things,” Donta said. “He needed more help than what was available in a seven-day or 30-day facility.”

But long-term residential centers are in short supply in Kentucky, especially in rural areas. Donta eventually found his son a bed at a Campbellsville center, almost four hours from Ashland.

Donta, who works in Frankfort, traveled to Campbellsville every week to see his son, but said Michael was largely out of touch with his family because of the distance.

At the center, clients were required to attend 12-step recovery meetings in the community. Michael didn’t have a ride, so he walked around looking for meetings. His father said treatment center officials told him Michael wound up “in the wrong part of town,” and they expelled him 90 days after he got there.

Michael went back to Frankfort with his father and attended 12-step meetings there for about a month. But in June 2010, Mike noticed that his son seemed sicker than usual.

“I knew he was using,” Donta said. “But he told me, ‘No Dad, I’m fine.’ ”

By then, Michael had lost his railroad job and was working at McDonald’s. He had no health insurance, so the family could only seek free programs, such as those available through the Recovery Kentucky initiative, a supportive housing program in which recovering addicts help each other.

“We called each of the ... men’s programs,” Donta said. “Nobody would take him. It was a months and months wait.”

Then in July 2010, Michael disappeared. His father, whose ex-wife has died, tried to call him dozens of times in the next few days — as did his girlfriend. They searched places Michael frequented.

On July 12, a cousin found him — hanging in an Ashland motel room. “He had nowhere to go. He didn’t want to go back to jail,” Donta said. “I couldn’t get him help.”

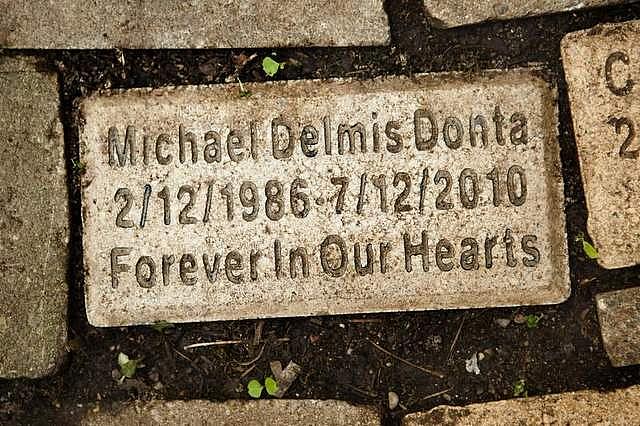

More than two years later, Donta visits his son’s grave in Ashland and he finds a measure of peace at the Children’s Memorial Garden in Frankfort, where a brick bears Michael’s name. He struggles to answer his 4-year-old grandson when he asks: “Where’s Daddy Michael?”

Donta has visited schools with Attorney General Jack Conway to talk about the dangers of prescription drug abuse. He gets several calls a month from people sharing their frustrations in trying to get treatment.

“I’ve heard story after story like that,” Conway said.

Donta said he often wonders what would have happened if his son had gotten the treatment he needed, when he needed it.

“It could have saved his life,” he said.