Did the Herald paint an unfair picture of the juvenile justice system? A look at the facts

This article and others in this series were produced as part of a project for the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship, in conjunction with the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Powerful lawmaker calls for juvenile justice review in wake of Herald series

Juvenile justice chief defends agency, calling abuses ‘isolated events’

An officer used a broom to beat juveniles into submission. They called it ‘Broomie.’

NAACP demands reform as lawmakers plan tour of lockup where youth was fatally beaten

Criminal record? Horrible work history? Florida juvenile justice would still hire you

At this juvenile justice program, staffers set up fights — and then bet on them

Dark secrets of Florida juvenile justice: ‘honey-bun hits,’ illicit sex, cover-ups

Lightning blasted his shoes off — and illuminated a pattern of abuse by staff

How small rebellions by Florida delinquents snowball into bigger beatings by staff

FIGHTCLUB: A Miami Herald investigation into Florida’s juvenile justice system

DJJ Secretary Christina K. Daly walks the grounds of the Miami-Dade lockup. Emily Michot

After the Miami Herald published Fight Club, its investigative series on Florida’s juvenile justice system, the state Department of Juvenile Justice issued a lengthy statement titled “Setting the Record Straight: Miami Herald Omits Facts, Ignores Reforms in Series Targeting DJJ.”

The department did not challenge any facts or data presented in the six-part series. “I will not deny, or discredit or downplay some of the horrible incidents that have happened,” DJJ Secretary Christina K. Daly told a state Senate committee on Oct. 11.

But in the secretary’s “setting the record straight” release, she stated that the Herald’s stories “do not accurately define the juvenile justice system in Florida or the many partners who are committed to serving youth and their families.” And she said the juvenile justice system was not receiving proper credit for years of reforms.

She has continued to defend the agency vigorously in appearances before lawmakers, characterizing the abuses the Herald described as the work of a small number of “bad apples.”

Here is a look at some of what Daly said the Herald failed to fully acknowledge. All statements are verbatim from the “setting the record straight” news release or from statements to lawmakers in a public forum:

“Florida has the lowest juvenile arrest rate in more than 40 years.”

In fact, the series did state that juvenile arrests in Florida are down dramatically. As the first article in the series noted, this is partly due to a decision made in 2011, championed by DJJ, to encourage the issuance of civil citations for some lesser, non-violent offenses rather than making arrests. It is also due to there being significantly less juvenile crime now than in the 1980s and ’90s.

This downward trend is not unique to Florida, raising questions about to what degree DJJ should take credit for it.

Nationwide, the number of juvenile arrests in the United States fell 56 percent from 2006 to 2015, according to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, part of the Justice Department. From 1996, when juvenile crime was at its highest, to 2015, youth arrests declined 68 percent.

“DJJ has reduced the use of residential commitment for low-moderate risk youth by 60 percent.”

Like youth crime, the commitment of youths to residential programs has dropped sharplyover the past decade throughout the United States, and it is difficult to see how DJJ is primarily responsible for that. The Justice Department data show that youth commitment dropped nationwide from 201 placements per 100,000 juveniles to 100 between February 2006 and October 2015.

During that span, nearly half of all states saw a drop in juvenile commitments of at least 50 percent.

“DJJ has the lowest recidivism for youth on probation that the agency has ever seen.”

Probationary programs were not examined in the Herald series, which focused on the conditions within programs where youths are confined.

Reporters did look at the recidivism rate for youths released from Florida residential programs. The current recidivism rate is 45 percent — meaning 45 of every 100 youths released from a residential program will either plead guilty or be found guilty of a new offense within one year of release.

That number is not trending downward. Over the past decade, it has swung between 39 percent (2005-06) and 46 percent (2009-10). It is conceivable that reducing arrests for minor offenses — as the civil citation program has done — boosts the recidivism rate within residential programs, since youths who commit lower-level offenses might be less inclined toward repeat offenses.

It is difficult to put this number in perspective, since no umbrella agency collects and compares state-by-state data on youth offender recidivism. Missouri, which has adopted a less-punitive approach to juvenile justice — becoming a national model in the process — claims a recidivism rate of 10 percent.

“Following the death of Elorde Revolte, the Department along with the Public Corruption Unit of the Miami Dade State Attorney’s Office completed extensive investigations into the allegations against staff [that employees offer treats for beatdowns]. Neither of these investigations proved these allegations to be true. ... DJJ has never, and will never, tolerate the outsourcing of discipline by staff to youth.”

The 17-year-old, whose first name is misspelled in DJJ’s “setting the record straight,” was savagely beaten by a mob of youths in the Miami-Dade juvenile lockup on Aug. 30, 2015. He died the following day. At least two youths claimed the beating was instigated by a staffer who became angry at Elord during dinner.

The state attorney investigated — and indeed said the allegations were “not corroborated by the evidence.” A federal investigation also was undertaken, although its status is unknown.

The state attorney’s office, while declining to prosecute, offered some pointed observations:

1) The investigation was hobbled by the poor quality of DJJ’s surveillance cameras — long a problem in the juvenile justice system — and by DJJ’s sloppy record-keeping. This made it difficult to pinpoint which and how many youths were in the area when the attack erupted.

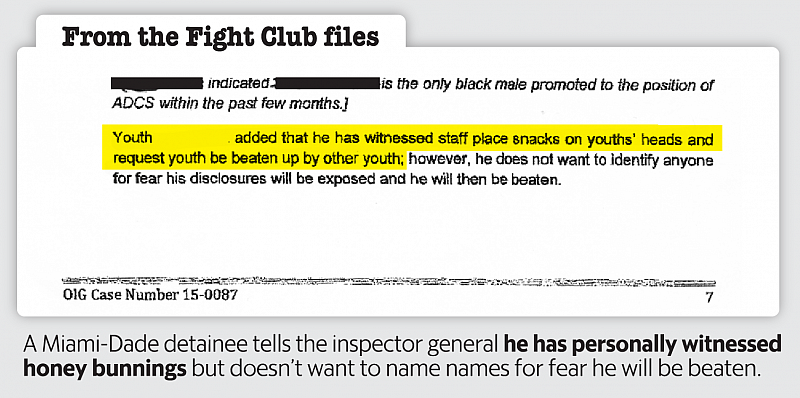

2) Investigators found “the number of claimants and similar nature of these claims seem to suggest that some [lockup] staff members likely engaged in the practice of offering honey buns or other food as a reward to youth detainees to carry out physical attacks.”

The state attorney’s office also felt that the youth who initiated this attack was likely lying about what prompted it — he said it stemmed from an earlier fight that was never documented — and that the boy might be more truthful when released from the lockup, away from the coercive presence of staff. Before they could re-interview him, though, the initial attacker was shot and wounded in an unrelated incident. Investigators decided to drop the matter.

In its parallel inspector general investigation, DJJ heard some of the same claims about staff-induced violence — including from an officer who said a detainee approached him the day after the attack on Elord and told him a staffer had instigated it. That officer, a 16-year-veteran, said a youth told him the alleged instigator “was going to place a honey bun on youth [Elord’s] head because he kept mouthing off.” The veteran said he was told the alleged instigator told Elord, in front of “the entire module, ‘We are going to get you.’ ”

The veteran said he didn’t report the youth’s disclosure because “the youth was a troublemaker” and he didn’t believe him.

While the state attorney’s office apparently found the stories persuasive, DJJ did not. The inspector general report said there was insufficient evidence to support or refute the allegation, without explaining what would constitute “support.”

Hence, the DJJ statement: “Neither of these investigations proved these allegations to be true.”

When Daly first spoke with the Herald, she said her agency did not tolerate workers outsourcing discipline. When pressed to offer evidence that DJJ had discouraged such practices, the department could provide no records showing it had addressed the problem via email, memo, new policy, annual performance review, or training curriculum.

Later, Daly denied such things occurred, despite a number of allegations in the series: “Allegations of honey buns or other rewards used as discipline or for attacking youth have been fully investigated and found to be unsubstantiated,” the agency said in a statement to the Miami Herald.

Videos included in the series clearly showed a worker refereeing a mixed-martial-arts-style bout and another sitting idly as one youth pummels another in a closet, and still another where a youth mounts a chair to turn aside a surveillance camera in preparation for a beating that was alleged to have been encouraged by staff. The beating is captured by another camera.

“DJJ maintains high standards for hiring practices.”

DJJ’s statement says it conducts a thorough background screening and criminal records check for every prospective employee, including a check for 50 offenses that disqualify an applicant from employment. The statement also notes that DJJ requires its contract providers to ensure that their hires meet the same “high standards.”

The series demonstrated how the department and its contractors have repeatedly hiredformer prison and jail officers jettisoned for abusing inmates, “improper relationships” with inmates, sleeping on the job, lying, insubordination, sexual harassment of subordinates and other misconduct. The series documented that DJJ permitted such hiring decisions without examining the state’s own personnel files, which would have revealed the reasons these employees had previously been found unfit.

When the Herald identified this pattern and began requesting specific personnel files, DJJ quickly issued a policy change. “Effective immediately, for all direct care positions, when a candidate has worked for a state agency, a copy of their file must be requested or an official file review must be performed before they can be considered for employment,” the DJJ chief of human resources wrote in a memo April 10.

When the Herald subsequently interviewed Secretary Daly in preparation for the series, she used the word “alarming” to describe the department’s past hiring practices. Daly said: “Weneed to use discretion. There are times that people pass background screenings and things like that. We have to do our due diligence to make sure we protect not only the children but the other staff that are working in these environments.”

Daly added: “The hiring practices are what they have been. They are. There’s not much I can do to change the past.”

And though DJJ had the authority to improve its own hiring practices on April 10, the agency says its hands are largely tied when it comes to policing the private providers that operate the state’s 53 residential programs. The department does criminal background checks to help screen hires by the private contractors but says it cannot, in most cases, veto a hire unless that person committed one of the 50 disqualifying offenses.

That may be how Uriah Harris — 11 arrests for resisting arrest (twice), domestic violence, aggravated battery, withholding child support and child neglect, among other offenses — came to be hired at Avon Park Youth Academy. He was discharged after several youths complained he was beating them with a broomstick he had nicknamed “Broomie.” Three separate investigations confirmed the youths’ accounts.

Asked about that specific hire, Daly’s spokeswoman, Heather DiGiacomo, said, “We expect discretion and common sense to play a role when evaluating every potential staff member.”

“Regardless of whether in state-run detention facilities or privately contracted residential commitment programs, any allegation made regarding care and safety of youth is thoroughly investigated by the Department to ensure youth are safe and staff are meeting our high standards of care.”

Polk County Sheriff Grady Judd offered a different view in August when he announced the arrests of three former high-level administrators at Highlands Youth Academy, formerly known as Avon Park.

Judd said the managers covered up widespread sexual misconduct between staff and detainees by destroying written statements, and concealed an attack on a detainee by hiding incriminating video.

Polk County Sheriff Grady Judd

The academy’s bosses “weren’t reporting what was occurring to DJJ, and DJJ was ignoring the obvious,” Judd told the Herald.

The series also made a case that cover-ups of staff misconduct are not rare. According to the state’s own data, DJJ investigated 971 claims over the past decade that a youth worker failed to report in timely fashion suspected misconduct, as required, substantiating 644 of the complaints, and another 484 reports that a worker falsified records, sustaining 269 of those.

In one case, the top administrator at the Fort Myers Youth Academy ordered a supervisor to rewrite his three-page account of a restraint. The original report documented the use of long-banned “pain compliance” techniques that left a youth sobbing after a worker gnashed his elbow into the teen’s broken jaw. The alleged abuse remained hidden for months — long enough for a video of the encounter to be destroyed. DJJ declared that the administrator had “no intent … to mislead” the department, and the manager was not fired or punished — until months later when he was caught failing to report another restraint.

“All staff in both juvenile detention facilities and residential commitment programs have unrestricted access for reporting incidents, without supervisor approval, to the Florida Abuse Hotline and the DJJ Central Communication Center. ”

The Herald presented multiple instances when this was not the case — at least according to youth detainees and sometimes the staffers themselves. At Fort Myers, for example, the same supervisor who was ordered to rewrite a restraint report also told investigators he was forbidden to report the incident to the hotline. “Things tend to get swept under the rug,” the supervisor said.

Youths at Fort Myers said they’d been “bribed” with fast food and intimidated into not reporting abuse. A nurse at the program told an investigator she resigned from the job because of widespread violence and “youths being called liars.”

Last year, a boy at the Spring Lake Youth Academy claimed he reported being punched in the face by a worker to a bogus hotline. The worker handed him a phone, the youth said, and told him to make his report. But the “operator” at the other end of the line never bothered to ask the youth where he was detained, or who had hit him.

“Our critics took the opportunity to pick and choose which incidents they would use to paint this system as a systemic abuse. They selected 78 program and management reviews, and 84 [inspector general] investigations, the most critical in nature of incidents this agency has experienced. Ultimately, these incidents reported in the series reflect less than one percent of all incidents originally provided.”

Daly said this to the Senate Committee on Criminal Justice on Oct. 23. She also said the events that were detailed in the series represented a “small percentage of substantiated incidents.”

She omitted the following: The series documented, through DJJ’s own data, that during the last decade youths or witnesses reported unnecessary, excessive or improper force 4,092 times — on average, more than once every day. Of those allegations, 1,014 were substantiated. Over the same decade, the agency investigated 1,455 claims of workers failing to report in timely fashion misconduct or falsifying official records, sustaining 912 of those.

The data also included 62 complaints against staff involving “sexual abuse,” none of which was substantiated — although the series included seven workers who were criminally charged with sexual misconduct. It also included 166 investigations of improper conduct of a “sexual nature,” 21 of them verified, and another 142 complaints of improper conduct resulting from a “staff/youth relationship,” substantiating 53.

For the youths who experienced this, and their parents, the consequences could be traumatic.

“Accountability is at the forefront of everything we do. We want to hold ourselves accountable, just like we want to hold our providers accountable.”

... “none of the incidents reported in this series were unknown or a surprise to the department. Each incident was met with accountability and the necessary changes and procedures in accountability were made to improve our system.”

The Herald’s reporting found several examples of DJJ and provider staff repeating the same mistakes or misconduct, sometimes over a number of years. One example involved the agency’s oversight of surveillance cameras. As far back as 2000, DJJ inspectors had reported that investigations into misconduct at detention centers in Miami and elsewhere were thwarted by the use of outdated and poorly functioning video equipment.

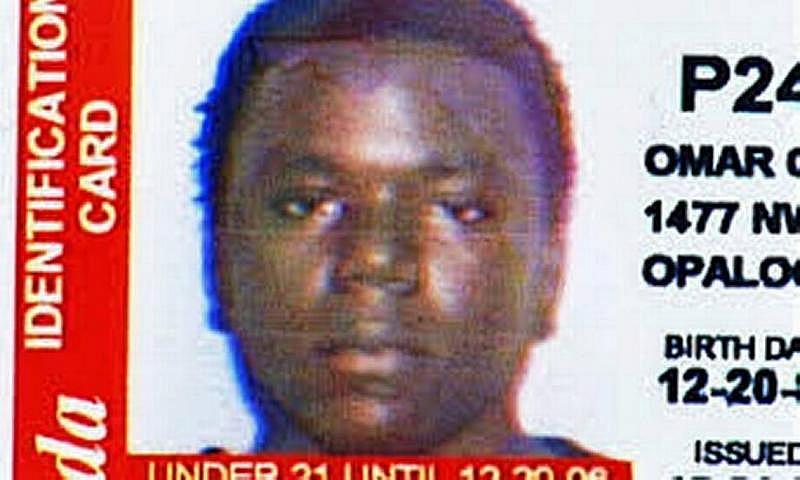

In 2003, when a 17-year-old died an excruciating death from a burst appendix at the Miami lockup, a grand jury complained: “While we understand that the existence of working surveillance cameras and videotaping equipment might not have saved the life of Omar Paisley, we are mindful of the fact that it could have helped us tremendously during our investigation.” The 2015 investigation of Elord Revolte’s death at the same lockup was similarly hindered by outdated surveillance equipment.

The grand jury report, dated Jan. 27, 2004, also lamented the “many departmental practices that appeared to result in the hiring and retention of unqualified and incompetent staff.” The report added: “We were disturbed to learn of the many [DJJ] employees with sordid criminal histories. We felt strongly that the individuals charged with caring for and rehabilitating our children should not have a history of engaging in destructive criminal activity or serious, pending cases.”

Yet, in addition to the Uriah Harris case, the Herald reported extensively about one man who was hired as a youth worker while he was on probation for punching a severely disabled man he was supposed to be protecting at a state-licensed group home. The worker later was arrested for clubbing a DJJ youth in the head with a flashlight — for which he was placed on probation, again.

The Miami grand jury was aware that its report could serve as a road map to reform.

In a footnote, grand jurors stated: “We know this case will remain visible in the system for years to come.”

Mary Ellen Klas of the Herald/Times Tallahassee bureau contributed to this report.

[This story was originally published by the Miami Herald.]