An epidemic: Domestic violence in Calif.'s Del Norte County (Part 1)

Emily Cureton’s reporting was undertaken as a California Health Journalism Fellow at the University of Southern California's Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

An American dream undone: Domestic violence in Calif.'s Del Norte County (Part 2)

Native communities hit hard by domestic violence in Calif.'s Del Norte County (Part 3)

Del Norte Triplicate // Bryant Anderson

By Emily Cureton and David Grieder

For many people living in Del Norte County today, it’s a crisis. For others, it’s become normal, part of surviving.

Often hidden behind closed doors, sometimes ignored by onlookers, domestic violence is undeniably woven into life here.

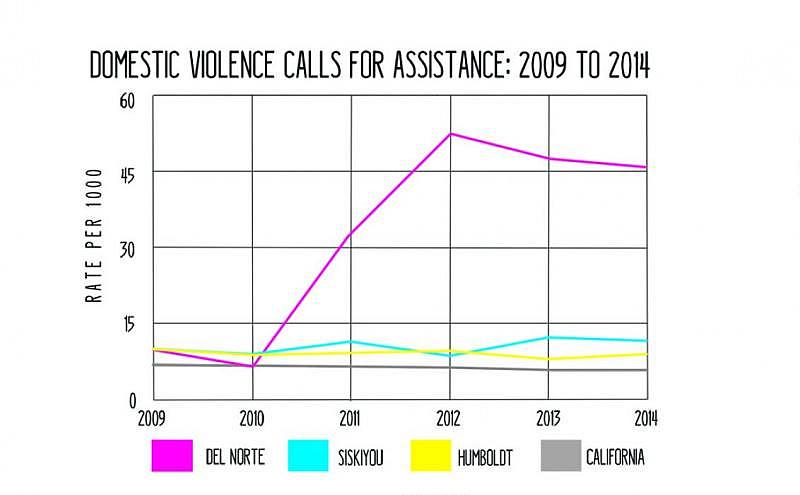

And it’s reported here at a higher rate than anywhere else in California.

Lately, Del Norters call police to report domestic violence eight times more frequently than the statewide average. Five years ago, this county’s call volume was right at the state average, around 6 out of every 1,000 calls to police.

The latest counts here show local law enforcement recorded 46 domestic violence — DV — calls for every 1,000 calls in 2014. The county with the next highest rate–Glenn County—got only 18 per 1,000.

Meanwhile, less than 8 percent of calls for assistance led to DV-related criminal convictions in Del Norte courts in one recent year.

Of 908 calls to Del Norte dispatch reporting domestic violence in 2014, some 184 people were arrested. Last year, 1,146 calls to report domestic violence came in and 190 people were arrested on DV-related charges as of mid-November.

An average of 83 people were convicted each year of DV-related crimes from 2009 to 2012, the latest year for which court conviction data is available.

Law enforcement and experts in the field say there’s reason to believe convictions, arrests, and 911 calls reflect only a fraction of the actual violence and abuse.

“We typically aren’t involved the first time it happens, or the second, or even the third time, so there’s this long-standing history and a lot of times the victim struggles to believe that law enforcement is actually going to help them,” said Del Norte County Sheriff Erik Apperson.

“It’s a huge epidemic,” said Jodi Hoone, a longtime local advocate and coordinator of services for people experiencing domestic violence, now heading up programs for the Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation.

National research indicates for every four women assaulted by an intimate partner, one will report it. With men, reporting is even more unlikely.

So why are there are so many calls to report now?

No easy answers emerged through many interviews with those who have experienced domestic violence here and those who respond to their calls for help.

Many victims said they wouldn’t call the cops, fearing either retaliation, or as the sheriff said, feeling as though law enforcement couldn’t help them.

“I never called the police,” one survivor of repeated sexual assaults said in a survey posted to local social media groups, “I wasn’t sure if they would respond. I wasn’t confident that I could adequately describe the incident, and I feared the perpetrator coming after me.”

Another person wrote: “Domestic violence affects everyone differently. One child may grow up to be strong and gain self-confidence through refusal to continue life that way, another may grow up to be an abuser, still another may grow up afraid of life, afraid to take chances. There is depression, eating disorders, and other issues that arise because of DV. Sometimes people die and those who survive feel guilty. Domestic violence contaminates whole families, not just the one abused. Abusers don't stop.”

Others said treatment for batterers is essential. Social workers who run those treatment programs said the stress of unemployment, poverty and addiction drives abuse, breeding trauma for generations. One judge linked the rise in family violence to the U.S. history of genocide of Native Americans.

One longtime advocate for victims of domestic violence said we should celebrate the rise in calls locally, as evidence people are being more proactive.

A woman who works with batterers thought the truth murkier.

“I think nobody really knows unless they are behind those reports, the stem of why people call,” said Lori Nesbitt, a Yurok Tribal probation officer and facilitator for the tribe’s Batterer’s Intervention Program, or BIP, a kind of group therapy model for treating abusers.

Their victims, she thinks, “are getting more desperate.”

Calls for help

One came in at 1 a.m . on Oct. 30. The dispatcher radioed a sheriff’s deputy:

“Female reports that her boyfriend, a Joshua Musser, has a baseball bat and is swinging it around. She’s afraid of him. At this time the female subject has locked herself in her room.”

“Copy. Is he inside the residence? Or Outside?” the deputy responded.

“He was outside. She said she was standing on the porch. I told her to go in the house. When she went in she said he grabbed the door. He may be inside now, but she said she’s feeling better. She’s got herself locked in her room. I told her to call back if she, um, gets more concerned,” the dispatcher said.

The deputies arrived, but did not arrest Musser.

“The deputies left it at both parties agreeing to sleep in different parts of the house,” according to DNSO Cmdr. Bill Steven.

Swinging the bat around was not a specific-enough threat, Steven said, he needed to hit her, or verbally threaten to hit her for the deputies to arrest him.

Sheriff’s Cmdr. Tim Athey, now retired, added: “Deputies are obligated to treat every incident as something in total isolation… Since there was no evidence in this case of battery against (name withheld), they did not have sufficient grounds to place an arrest.”

Later the same day, she called 911 again. More than an hour later, deputies arrived.

“The reporting party states that her boyfriend Joshua Musser is outside of her residence scouting a 415 (disturbance), and she won’t take him into Crescent City to pick up his check,” the dispatcher radioed.

“There is an issue of domestic violence in the past.”

Again, Musser was not arrested when deputies made contact with him.

Within three days of this call, he was served a court protective order, ordering him not come within 100 yards of the same woman. It stemmed from an entirely separate assault against her that occurred six months prior, at the same address.

The police report from that day in April describes a chaotic scene, “indicative of a physical altercation.” Musser had already fled when the deputy observed it. The television in the bedroom was knocked over, a window shattered in a struggle. The woman told the officer that after she tried to break up with him, Musser grabbed her by the hair and held her down.

“She requested an Emergency Protective Order, if Musser was located and taken into custody,” the DNSO report states.

Musser was eventually arrested, charged, and convicted. The sentencing for the April assault came down in November, 10 days after the alleged baseball bat incident in October, when deputies left it at both parties agreeing to sleep in different parts of the house.

Musser was fined $920, ordered to serve three years probation, assigned 120 hours of community service work, banned from owning a firearm for 10 years and required to enroll in a 52-week Batterer’s Intervention Program.

In December, Musser was arrested again, charged with domestic violence crimes and meth possession.

After almost a month in custody, Musser received a nearly identical sentence for similar charges this week. On Feb. 2 he was sentenced again to community service, three years probation, and fined $920, not including public defender fees. He was also given 180 days in jail.

While issuing charges on Dec. 10, Deputy District Attorney Annamarie Padilla said she would invoke Musser’s history of domestic violence during prosecution.

She would have referred to a 2012 incident, when Musser was arrested and accused of battering a different female partner. In that case, he also returned to the household not long after, despite a restraining order. Within two months of the arrest, the victim called 911 again. He fled before officers arrived in Klamath.

Investigators photographed choke marks on the victim’s neck and a fresh bruise on her face. A deputy offered her a ride to the emergency shelter, which she declined. He gave her a printout with information about services for victims like her.

“She declined any medical attention for her injuries and stated she would seek a restraining order on her own,” the deputy noted in his report.

“It just never ended up good.”

One out of every 10 women victimized by a violent intimate will seek professional medical treatment, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics and the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Kristin is part of this overwhelming majority.

A 29-year-old Crescent City woman, she doesn’t know exactly how many times she’s been choked. She described what it feels like to have broken ribs, to have her eyes gouged. She said her abuser bit her finger so hard the nail fell off and he pistol-whipped her.

Arthur Pinder, left, at the African American Cultural Festival. Pinder used to visit the health clinic in Warren to treat his asthma. Credit Christine Nguyen, The Daily Dispatch / For WUNC

“The houses are so spread out from each other that no one could hear me scream, unless I was at their window or door knocking,” said Kristin.

She said she never called police or went to a hospital, partly because childhood trauma taught her to stay silent and because of drug addictions and a petty criminal record that began in her teens.

“I’ve been abused my whole life, first by my father and then my first kid’s dad. It just never ended up good,” she said.

She lost faith in the intervention system from an early age, after telling a teacher what was going on at home. She said the retaliation was swift and the threat dire: she would likely be placed in foster care or a group home if she said anything again.

Kristin’s latest abuser is the father of two of her children. He’s never been convicted of DV-related charges in Del Norte County. He was recently charged with a long list of violent, felony offenses.

Kristin said she’d “probably be dead without the drug/alcohol counseling, transitional housing and vouchers she’s getting from county and state programs.

“I hate to say that, but he’s tried to kill me two, three times now. Each time I would go back because I’d be scared, or you know, the whole cycle of violence. I’d always go back,” she said.

The price of reporting

People live with abuse for many reasons, death threats among them.

Shelagh Carrick said some ask, “Why did she stay?”

Carrick is the shelter manager at Harrington House, Crescent City’s only emergency shelter for families experiencing domestic violence. It’s licensed to offer temporary housing for a maximum of three continuous weeks.

Carrick said Harrington House is a safe place in a crisis. It’s not a longterm solution.

She said a lot of things can happen to a family on the other side of reporting. In many cases, a family can become destitute and homeless if one member gets arrested, fined, or required to pay for a costly 52-week Batterer’s Intervention Program.

Carrick has seen it happen, over and over.

“A lot of women give up because they are in trauma and they are being retraumatized on a consistent basis. So, the enemy they know becomes less scary than the enemies they don’t.”

Carrick seemed certain: “If we could improve the financial stability of victims, we would greatly improve the outcomes.”

There’s an office in the Del Norte County Courthouse where domestic violence victims can request financial assistance, as well as help navigating the judicial system.

But Del Norte’s Victim/Witness Program isn’t allowed to give more than $100 in cash per individual and largely relies on community donations to help people out with basics like gas and grocery vouchers, said program coordinator Alison Baxter.

Her office saw 392 crime victims last year, 40 percent of whom identified as domestic violence victims when they sought services there. The total budget for the program, a figure including two full time employees, was $126,000.

Baxter and a colleague mostly help victims fill out myriad forms: applications to get a restraining order, applications to keep one in place, applications to the California Victim Compensation Government Control Board in Sacramento.

The agency can give bonafide victims much greater sums or vouchers to help them start a new life. The money comes from restitution fines paid by convicted offenders, money the control board redistributes to crime victims across the state.

Payments to crime victims from Del Norte County have declined dramatically in the last five years. Payments to domestic violence victims here have dropped about 90 percent.

Control board officials said since restitution payments are relatively steady, the reasons aren’t budgetary. They said the local Victim/Witness office simply didn’t submit as many applications.

Del Norte’s Victim/Witness Program mostly helps people fill out applications for restraining orders, which can keep one person from contacting another under penalty of arrest. State law requires the person seeking the restraining order to contact the person they want kept away or the order won’t be granted by a judge.

A text or a note on the car window will suffice, Baxter said, and there’s no requirement for a receipt of confirmation.

Officer staffing issues

Melody turned 21 a few months ago. She spent her teens in Del Norte. She said she moved out of the family because abuse became intolerable.

Soon after, and still a teenager, she became homeless. She began camping around Crescent City. At first she hid from the police, then from a man she says stalked and sexually assaulted her.

“I tried reporting it, but the cops weren’t very nice to me because I wouldn’t give them too many details. They got upset with me. They were rushing me into it and I told them I needed time to open up, because it’s not something you can just… You can’t just like, start saying paragraphs about it without getting really emotional.”

From a police officer’s perspective, describing an assault and allowing photographs of the injuries is critical for prosecuting offenders, said Apperson.

“A lot of times (victims) don’t want to go through the clinical part of, ‘OK, let me see the bruise and let’s move this article of clothing so I can hold a ruler up to it and take a picture and oh, by the way, I know you just trusted me enough to tell your whole story, but now let’s do it again and let’s make sure my recorder is working because we are going to play this for a whole jury and for a courtroom full of people,’” Apperson said.

Meanwhile, turnover is high at the sheriff’s department, the county’s principal law enforcement agency. The total number of DNSO deputies has declined by nearly a third in the last few years.

“In 2010, we had closer to 29 (deputies), and at the end of 2014, we had closer to 25,” Apperson said.

As of mid-December, a spokesperson for the department tallied 19 deputies. This includes investigators and court bailiffs, jail and boating staff. Eleven were on patrol to take emergency calls.

Most domestic violence victims are women. When he was interviewed in November, Apperson said all patrol deputies are men.

Enforcement issues

“The bottom line is, we as law enforcement have to think about putting the bad person in jail and we have to think about things from the punitive side. A lot of times in these DV calls, the victims or survivors want to be consoled first, they want to be removed or at least made safe. And we have to think about the prosecution side of it. Because if we don’t prepare an investigation that gives the District Attorney everything they need, then we really haven’t served the victim,” Apperson said.

District Attorney Dale Trigg agreed “it’s critical to have victims interviewed right away and get their injuries documented. So that if they do recant later, I have their prior statements to law enforcement.

“Since I’ve been in office we’ve sent several people to state prison on DV cases with recanting victims,” he said.

Still, the majority of domestic violence and sexual assault arrests in Del Norte don’t lead to prosecutions, let alone convictions. Trigg pointed to inadequate, untimely reports from deputies and police officers. He said these critical reports are sometimes not filed for weeks, long after an accused person has been released from custody.

Then he added:

“And it’s not always a law enforcement issue. Usually it’s not. The facts are what they are. If you go out to a scene and a woman that has injuries and she won’t tell you how she got those injuries, you can’t just figure, ‘Well, I know how you got them and I’m going to arrest so-and-so.’ The officers can’t do anything about that except to try and get the truth out of people.”

The district attorney’s office, including Trigg and several other deputy DAs, has a lot of discretion over which cases to prosecute.

Sheriff Apperson said officers are supposed to make an arrest on a domestic violence call if they can establish a “primary aggressor.”

He explained: “You know there was a time not that long ago where if the victim or survivor didn’t want to press charges then you would just separate the two people, maybe take one to a friend’s house and drive away. Now in California, if you can establish what’s legally defined as a primary aggressor, then you are required to make an arrest.”

But often times, an arrest soon leads to another crisis.

“When people often blame the victim, they don’t realize how hard it is to talk about stuff like that,” Melody said. “And they say, if you aren’t going to report it, then it’s basically your fault. I’ve been told that a lot. But I was afraid things would only get worse.”

[This story was originally published by Del Norte Triplicate.]

Photos by Bryant Anderson/Del Norte Triplicate.