Even if your relatives had diabetes, you don't have to

West Virginia is among the top five on just about every national chronic disease list. The state leads the nation in diabetes and obesity, according to the Gallup Healthways poll.

Surveys show that many West Virginians do not realize obesity is a leading cause of many chronic diseases. Many also feel those diseases are hereditary, and there is nothing a person can do to prevent them.

The state's children raise major red flags for the future. West Virginia University screens thousands of schoolchildren every year. In 2010-11, they found that 24 percent of fifth-graders have high blood pressure, 26 percent have high cholesterol, and 29 percent are obese. Eighteen percent of kindergartners and 23 percent of second-graders are obese.

There has been little public discussion of this problem. "The Shape We're In" project aims to stir up that discussion. Written and photographed by Annenberg fellow Kate Long, it will be divided into three parts in The Charleston Gazette, the state's largest newspaper:

• Children at risk

• Programs that work

• Communities making a difference

Some segments will be accompanied by West Virginia Public Radio pieces.

Part 1: "This is a public health emergency"

Part 3: Putting the pieces together

Part 4: Health officials say W.Va. can reverse its chronic disease numbers

Part 5: W.Va. man: diabetes programs work

Part 7: Daily activity affordable, Department of Education says

Part 8: Wood researchers: Active kids do better academically

Part 9: Rocking the gym at 7:30 a.m.

Part 10: Nebraska school district lowers obesity rate

Part 12: 'Everyday heroes' saving own lives

Part 13: W.Va. ranks first in heart attack, diabetes, eight other categories

Part 15: Great Kanawha food fight

Part 17: W. Va. slammed with sugar

Part 18: Glenda and Jill vs. diabetes

Part 19: This is how bad diabetes can be

Part 20: Recognize diabetes before it's too late

Part 21: Logan hardest hit by diabetes

Part 22: Even if your relatives had diabetes, you don't have to

CHARLESTON, W.Va. -- "West Virginia patients come into my office," Dr. Frank Schwartz said, "and they'll say, 'Yep, Mom had diabetes, and it caused her to go blind when she was 63. So when do you think I'll get diabetes?'

"And I'll say, 'You don't have to get diabetes. You can prevent it.'

"But it's like they didn't hear me. They'll say, 'But when do you think I'll get it? When do you think I'll go blind?'"

"And I'll say, 'You can cut your risk of diabetes in half if you exercise for a half hour three times a week and eat a reasonable diet,' and they'll say, 'I hope I won't lose my leg.'

"It happens again and again," he said. "There's this very powerful cultural story line in Appalachia that says, if your grandma and your dad had sugar, you're going to have it, and there's not a thing you can do to stop it, and you'll go blind and your leg will be amputated, and your kidneys will shut down.

"It's completely untrue, but that doesn't seem to stop it. Before we can start preventing diabetes on a wide scale, we need to deal with that story. If people believe there's nothing they can do, they won't try to prevent it."

Frank Schwartz, M.D., is an endocrinologist. He treats diabetes. He grew up in Parkersburg at a time when a kid "left the house in the morning and played all over town and didn't come back till supper. We walked two miles to school, so very few of us were heavy."

Now he directs the diabetes/endocrine program at the Appalachian Rural Health Institute at Ohio University in Athens, where he treats a lot of West Virginians.

He thinks a lot about the myths surrounding diabetes: Why is it so hard to convince people they can keep themselves from getting diabetes, even if their grandmother and mom had it?

He also obsesses over a second question: "Why does Appalachia have a higher diabetes rate than most of the rest of the country?" The two questions are somehow connected, he thinks.

Myth: Black people get diabetes because they're black

In 2010, Marshall University professors Richard Crespo, Lawrence Barker and colleagues found, through analysis of Appalachian Regional Commission data, that people in distressed Appalachian counties get diabetes two years earlier than the national average.

"Distressed" means the average income and education levels are low, and services are scarce.

Six years earlier, in 2004, Schwartz and his students basically found the same thing. They surveyed people in the 11 "Appalachian" Ohio counties located next to the West Virginia border. In those eleven counties, all of which qualify as "distressed," 11.3 percent of the people were diabetic, compared to the overall Ohio rate at the time of 7.2 percent. "They were in line with West Virginia, not Ohio," he said.

Schwartz and students asked diabetics how old they were when they were diagnosed. Thirteen percent said they were under 21. "That's more than twice the national rate estimated by CDC," Schwartz said.

How many West Virginia young people were diagnosed at a similar early age? "Nobody's ever asked, as far as I know," Schwartz said, "but it stands to reason that it would be happening.

"Somebody should find out," he said. "It's an established fact that people who make less money and have less education develop diabetes and heart disease more frequently, so you'll see more children with problems in distressed counties, too."

West Virginia leads the nation in diabetes and obesity. Eighty percent of diabetics are obese. "Obesity is pushing the diabetes explosion," he said.

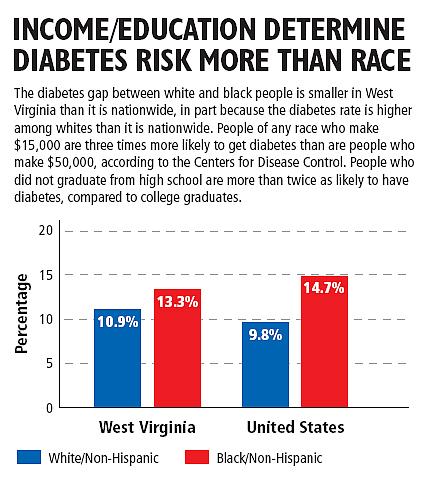

"Race is not causing it," he said. There's another myth, he said, that black people are genetically likely to be obese and get diabetes, so they are somehow responsible for the nation's diabetes problem. "That's not true.

"When I was a young doctor in Parkersburg, I'd go to national conferences, and experts would be saying diabetes rates were going up because American Indians and African Americans are genetically more disposed to get diabetes. And the West Virginia doctors would be sitting there saying, 'But we see those kinds of high rates at home, and we're 94 percent white.'"

"Back then, people assumed race was causing it," he said. "They weren't stopping to think that African Americans and American Indians also had less money and less education on the whole.

"Since then, a lot of research has shown that people who make less money and have less education are more likely to get diabetes, no matter what color they are. Just like people of any color who eat more calories than they burn off are more likely to gain weight.

"In West Virginia, a high percent of white people have less money and education than the national average. A lot of white people are obese."

West Virginians of any color who make $15,000 are twice as likely to get diabetes, compared with West Virginians of any color who make $50,000, according to the Centers for Disease Control. And people who went no further than high school are more than twice as likely to get diabetes than people who have college degrees.

"So how do we convince people they can keep themselves from getting diabetes, even if their grandmother and mom had it? Or if they're black and they've been told they'll probably get it."

Some states are doing billboard and TV/radio ads to tell people they can prevent diabetes. West Virginia has not yet done so.

"When you manage to get people past the story, good things often happen," Schwartz said. "Many people do just need good information. But information alone may not be enough."

Unemployment and prescription drug abuse and diabetes all impact each other, he said. "We talk about each of these things as if they were separate," he said, "but they aren't. Where there are higher levels of poverty, illiteracy, tobacco use, unemployment and now prescription drug abuse, there are also higher levels of depression and chronic disease. It's all interconnected.

"Communities have a part in this," he said. "If there's no grocery store, for instance, and the only food is at the Marathon that sells beer, chips and milk, it makes it harder for people to improve their diet." If there's no safe place for older people to walk or no gym where overweight children and teenagers can be active, that can make it harder to exercise, he said.

"For a long time, we've assumed the medical establishment should somehow take care of chronic disease by itself. That's obviously not working. The problem has gotten too big, and it's becoming clear that this is something for whole communities to solve."