Flawed tracking may mask birth-defect clusters across U.S.

This story was produced as a project for the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism and the National Health Journalism Fellowship, programs of USC Annenberg’s Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

FDA agrees to review folic acid for corn flour to halt birth defects

How the state is missing chances to find deadly birth defect’s cause

Wash. state to tell families about genetic studies of fatal birth defects

State changing vitamin rule in wake of birth-defects probe

FDA weighs adding folic acid to corn masa to halt birth defects

Washington state is missing chances to find deadly birth defect’s cause

Maria Rosario Perez lived 55 minutes before dying of complications of a birth defect that left her without most of her brain or skull. Para ver subtítulos en español en el vídeo, presione el ícono. (Erika Schultz & Lauren Frohne / The Seattle Times)

[Click here to read the Spanish version.]

It’s difficult, often impossible, to uncover the cause of a birth-defect cluster. But the task is made tougher in Washington state and across the U.S. by a scattershot system that doesn’t routinely or accurately track cases that might signal alarm.

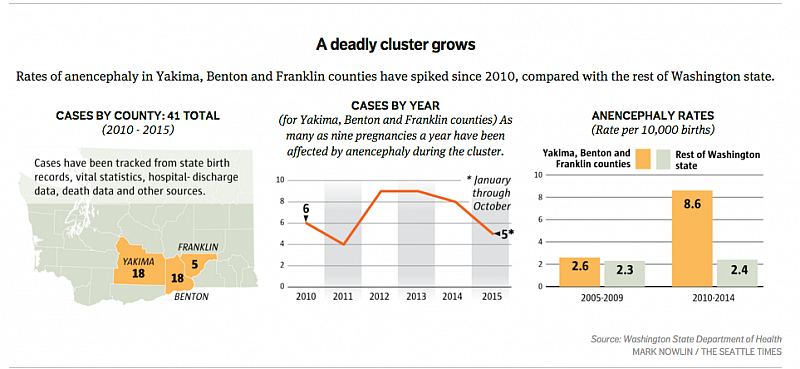

In Central Washington, it took an astute nurse at a small hospital to notice that an unusual number of babies were being born with anencephaly, a tragic neural-tube defect. She flagged the problem, triggering the investigation that continues today.

Washington is among 33 states without so-called “active” surveillance systems, in which investigators identify cases through direct review of sources, including medical records, hospital-discharge records, autopsy reports and outpatient-care records. Instead, the state has a “passive” system that relies on voluntary reports of nine serious defects, including anencephaly.

The trouble with that? Not all health-care providers report birth defects, including those that lead to fetal deaths, resulting in an undercount. State health officials estimate 2,400 to 3,200 birth defects are diagnosed among the 80,000 live births in Washington each year, but the actual number isn’t known.

Washington had an active surveillance system from 1986 to 1991, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), but the funding was cut. Annual costs for a passive system range from $90,000 to $450,000 to track 90,000 births, versus between $900,000 and $2.7 million for active surveillance, estimates show.

To get an accurate count in Yakima, Benton and Franklin counties, the area affected by the anencephaly cluster, state health officials have added “active follow-up,” increasing requests to hospitals to report cases and seeking medical records to confirm each report, said Cathy Wasserman, the state epidemiologist leading the investigation.

Questions about accurately tracking birth defects extend beyond Washington state. Of the nearly 4 million births in the U.S. each year, fewer than half occur in places with active birth-defect surveillance systems, a review of federal data shows. That means more than half of babies are born in states that may detect the problems — but also may not.

There’s another issue, too. Tracking systems rely on birth certificates to identify defects — and they can be notoriously inaccurate, according to Delton Atkinson, deputy director of the CDC’s vital-statistics division.

“Errors in the registration and transmission process, under-reporting and sometimes misreporting or misclassification have contributed to these long-standing, well-recognized issues,” he wrote in an email.

Combine that potential inaccuracy with a rare defect, such as anencephaly, and the numbers are likely to be “highly problematic,” especially in small geographic areas, Atkinson added.

For at least seven years, the CDC’s WONDER public-health database has provided birth-defect data, including anencephaly, for most large counties in the U.S.

Last summer, the CDC removed all county-level data for anencephaly and four other birth defects: cleft lip/palate, Down syndrome, omphalocele/gastroschisis and spina bifida.

The move followed inquiries by The Seattle Times about anencephaly cases in Texas and elsewhere because of worries about accuracy, Atkinson said.

“We concluded that these data should be dropped from this particular data dissemination system,” he wrote.

As a result, it’s not possible to easily tell how many cases of anencephaly or the other birth defects were reported at the county level.

[This story was originally published by The Seattle Times.]

Photograph by Erika Schultz & Lauren Frohne/The Seattle Times.