Food Insecure Korean Seniors Discover Market Match

The story was co-published with AsAmNews as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

A Korean Market Match shopper appraises the healthy produce at the Adams-Vermont location.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

On Wednesdays, Korean elders line up by a chain link fence around a lot behind St. Agnes Church in Los Angeles, 90 minutes early to the weekly Adams-Vermont Farmers’ Market.

They are enrollees of CalFresh, California’s version of the nationwide Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), or “food stamps,” for low-income residents.

At 2 p.m., they advance to a table where Hunger Action Los Angeles (HALA) employees will debit their electronic benefit transfer (EBT) cards for up to $20 and hand them an equal value of one-dollar coupons, doubling their spending power for farm-fresh fruits and vegetables.

Food security organization Roots of Change (ROC) started this program, Market Match, in 2009 to incentivize CalFresh members to buy healthy, local produce at nearly 300 participating open-air markets throughout California.

The arrangement also boosts the revenue of farmers and vendors. According to the program’s 2023 Statewide Impact report, every dollar invested in Market Match last year yielded three for the local economy.

And between 2017 and 2023, the program brought $30 million into the state in matching federal competitive grants won by the California agricultural department for additional Market Match support.

Many monolingual Koreans have recently become aware of Market Match, just as the program faces potential funding cuts in an attempt to offset California’s $27.6 billion deficit.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s budget proposal cut $33.2 million of the $35 million allocated to Market Match. The state Assembly and Senate rejected this in its joint budget proposal on May 29 and commenced hearings, heartening lobbyists for the program and a Save Market Match coalition of state representatives and stakeholders.

On June 13, the California legislature passed a balanced budget of $293 billion on June 13, just in time to meet the constitutional deadline of June 15th for finalization. All Market Match funding was restored.

But now, the behind-the-scenes negotiations have only just begun. CalMatters explained why a finalized budget will continue to undergo heavy editing. And the governor can still veto line items in that budget.

If the cut makes it into the true final budget, the flourishing Market Match program could come to an end.

Advocates rally for the California legislature to retain anti-hunger measures in the 2024-25 state budget, including preservation of support for Market Match and an increase in the CalFresh minimum benefit.

Photo by Frank Tamborello

Without it, food-insecure Koreans who have joined the half a million people accessing its benefits will lose a crucial safety net. CalFresh seniors, who often only have $10 to $20 on their EBT balance at best at any given time, will not be able to afford as much healthy produce as they could before.

Frank Tamborello of Hunger Action Los Angeles (HALA), a food security organization that administers Market Match at 38 markets including Adams-Vermont, said that Koreans came to the site not just to reap benefits but because they could find and afford the food they wanted and needed.

“They’re going to buy less food and have less food – that’s pretty bluntly how it’s going to be,” he said, if the cut goes through.

Last to the table

In-sik Kim, new to L.A. and Market Match, got some eggs after a two hours in line at the Adams-Vermont Farmers' Market. Hunger Action Los Angeles director Frank Tamborello warned that "eggs don’t grow on trees" - matching coupons are for fruits and vegetables only. But Market Match helps CalFresh shoppers save their EBT funds for other goods while also being able to afford nutritious produce with their matching coupons.

On a market day in May, an 80-year-old Korean man with a cane who declined to identify himself pointed to the groups of Korean ladies waiting for their market coupons. He said that they always bought a variety of products, whereas he was focused on eggs.

“If I eat three to five a day, I don’t feel hungry,” he said.

Market Match helped him start affording eggs, classified as poultry, with his EBT funds. The coupons, applicable to produce only, meant that choosing to buy eggs with his EBT money to fill his stomach no longer meant foregoing nutritive fruits and vegetables that he could now purchase with his matching coupons.

He flashed a sheaf of hoarded coupons, good as money. He could have gone to spend them without waiting, but stayed in the queue to gather more for a rainy day.

He discovered Market Match just a year ago and said that, to him, other Asian groups seemed to find and maximize benefits so much faster than Koreans do, regardless of language barriers.

“Koreans are always a step behind. It’s the community organizations’ fault,” he surmised, retreating for rest in a space where the Korean American Community Coalition (KACC) tent usually was, just not that day.

The Korean American Community Coalition (KACC) tent at the Adams-Vermont Farmers’ Market in April.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Cathy Choi, who founded KACC in 2021 to serve non-English speaking Koreans, didn’t know about Market Match when she applied for a county grant last year to support folks eligible for CalFresh. A county worker told her she should link up with a Korean American who was working at the Adams-Vermont market.

KACC was likely the first Korean community organization in L.A. to learn about Market Match and now promotes the benefits widely. The organization has also become a fixture at the market, notifying non-English speaking Koreans about KACC’s social services and senior classes in everything from tech to dance.

How Korean seniors met their Market Match

In spring of 2023, the state’s social services department launched the California Fruit and Vegetable EBT Pilot Project to encourage CalFresh recipients to eat more fresh fruits and vegetables.

The pilot debited up to $60 from people’s EBT cards per month, distributed a matching value of market coupons, and then credited their cards back with the same amount.

Shoppers could use the rebates anywhere that takes EBT, unlike before, when they had to permanently withdraw up to $20 from their benefits to get $20 in coupons, all for use at the issuing farmers’ market.

In L.A. county, where 12,587 of 131,587, 1 out of 10, current Asian CalFresh recipients stated a preference for Korean language services, the enticing $60 match synergized with years of grassroots efforts to help monolingual low-income Korean community access more social services overall.

In April 2023, when the pilot began, the attendance of Korean CalFresh members exploded at Adams-Vermont market, resulting in overwhelming crowds, hours in line, and fisticuffs over cutting.

In April 2024, when the pilot project tapped out, the program reverted to its original format of matching $20 per week for spending in farmers’ markets.

In April alone, HALA tabulated revenues of $16,000 at the Adams-Vermont, triple what they were pre-pilot, making the location the top earner among the organization’s 38 markets.

And many of the Korean customers who had found Market Match through the pilot returned, while new Korean shoppers kept coming by word-of-mouth.

Feeding the need

“I can’t stand it when people ask why so many Koreans are suddenly at this market,” said Susan Park, from beneath a tarp on a hot day in April. HALA hired Park and her brother during the $60 pilot launch to provide crowd control and essential Korean language interpretation at Adams-Vermont.

Susan and Mike Park, the sibling duo that manages crowds at Adams-Vermont in English, Spanish, and Korean.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

She said that the market only seemed overtaken by Koreans because the community previously had no idea of the services and nowhere to go to receive culturally and linguistically competent assistance.

HALA had already begun to recruit bilingual Korean-speaking staff as the number of Koreans crept up at Adams-Vermont years before the implementation of the pilot program.

Jiho Jeong-Kim, a college student also employed part-time by HALA, processed rebates at the matching desk alongside veteran manager Susana Tapia and other part-timers.

Bilingual in Korean and English, Jeong-Kim was able to field the bafflement of new and repeat Korean customers amid technological difficulties with the EBT debit machines.

Jiho Jeong-Kim, student and HALA employee, interpreting for Korean CalFresh members at the Adams-Vermont market.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

By Jeong-Kim’s last day at the market after eight months, she had seen the consumer base go from half Hispanic and half Korean to almost entirely Korean. She will continue working behind the scenes to help update HALA’s website and other materials.

In a video call with AsAmNews, Jeong-Kim, simultaneously focusing on her final quarter at UCLA, said, “I feel like I’ve been doing a lot of work for HALA even though my initial role there wasn’t very deep, because I’ve grown to actually really care about this population.“

Where everybody, or nobody, knows your name

Tamborello, who became the principal co-founder of HALA in 2006, said that Korean shoppers first appeared at the Adams-Vermont location in February 2014.

He also remembered when the adult day health care center of the adjacent Korean Catholic church dropped congregation members off at the market.

“There were two and the next week, there were four and the next week there were eight. It sort of went up like that,” he chuckled. All of them were seniors with supplemental security income (SSI), including Koreans who immigrated to the U.S. in their old age.

Frank Tamborello, principal and co-founder of Hunger Action Los Angeles, visits the market after returning from a visit to representatives in Sacramento and delivering meals to housebound folks in Los Angeles all day.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

When the law expanded to allow (SSI) recipients to receive food stamps in 2019, Ellen Bong, a shopper and respected member of the Korean community, helped process CalFresh enrollments of Korean seniors because none of the HALA staff was Korean-speaking.

Tamborello also got to know 77-year-old Jin Taik Chung, who stumbled upon HALA’s table ten years ago.

Chung came to the U.S. in 1978 after studying in Japan. When the last of his international trading ventures failed during the recession, he renounced his ambitions and decided to live simply. Soon, he was a senior with SSI.

“It’s nothing complicated,” Chung said, in regard to how the Adams-Vermont market became almost exclusively Korean in the past year. “Everyone’s here because they’re giving out a lot of money.”

He said that all it took to alert more Koreans to Market Match was to tell an elder in an apartment complex with other Koreans.

“Everybody will know in an instant,” he said.

He said that Koreans his age, 65 and up, were diligent about finding benefits.

“They remember the war. They came over here to raise their kids in a new country, and gave everything they had to make sure they went to good colleges. It’s in their muscle memory to fight,” he said.

On a market day in May, Adams-Vermont shopper Jin Chung caught up Izzy, the self-proclaimed “honey guy” whom Chung befriended over the years. Izzy prodded Chung to show off the lurid photos of his mountain frostbite from when he was famously rescued after three days on snowy Mt. Baldy last year. Chung obliged. Izzy reciprocated by flashing an image of a sail jellyfish he’d almost stepped on at the beach.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

The market has become something of a community.

“We’re all have-nots here, so no one can judge,” said one man, in his seventies. He and his wife were at Adams-Vermont for the first time after hearing about the market from a fellow resident of the senior apartments.

He did not feel ready to be recognized by other Koreans at the market but said that more people in the community had to realize that receiving public assistance was a claiming of one’s rights, not shameful acceptance of handouts.

“If you don’t take advantage of your rights, you’re just an idiot,” he said.

Potential for growth in NorCal

A recent study about high food insecurity and low CalFresh participation by Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, South Asian, and Vietnamese people called for more targeted outreach to Asian communities and better information about their specific needs.

That SNAP programs across the country like Market Match do not collect demographic data, which makes it difficult to gain insight into whether any given market is impacting the full diversity and needs of the people where it is located.

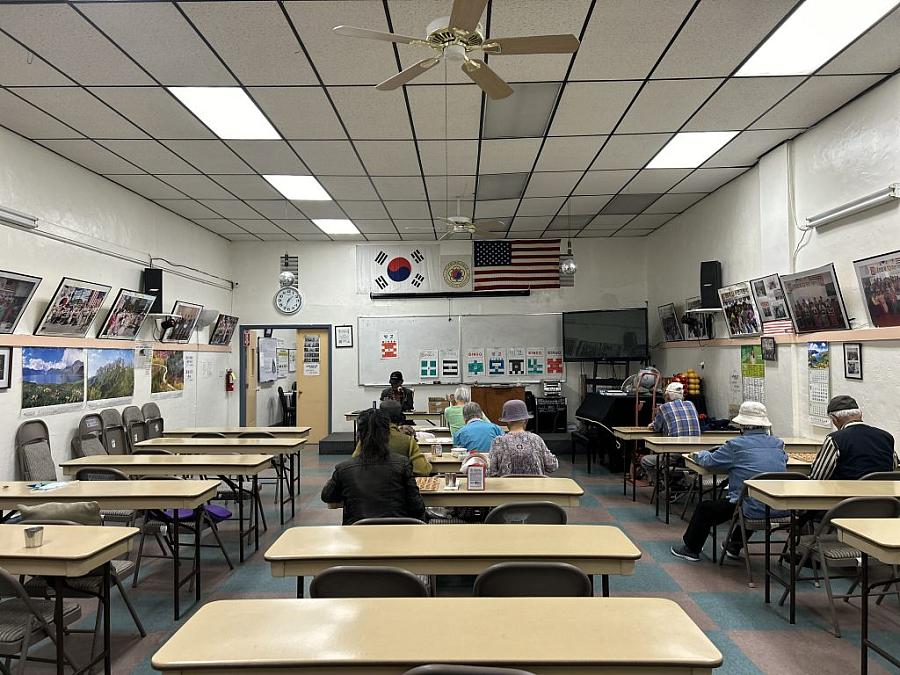

Seniors at the Korean American Senior Center of Oakland, after lunch and a visit from Korean American youth.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Minni Forman, director of the food and farming program at the Berkeley-based Ecology Center that manages Market Match for the entire state, said that the organization publicizes the program by informing county social services offices about it.

The center also provides translated materials in Spanish, Cantonese, and Vietnamese. A one-pager of information for distribution is available in Korean.

The New York-based Asian American Federation (AAF) of 70 member agencies devoted to Asian empowerment and well-being just released a commissioned national study of Korean adults. The study found that almost half of Korean seniors in L.A. and one in three Korean seniors in the Bay Area are living at or near poverty levels.

The data also reported that 81% of Korean seniors in L.A. and 78% of Korean seniors in the Bay Area have limited English proficiency – nationally, the rate of Korean seniors with limited English proficiency is 73%.

Seventy percent of the Bay Area’s Koreans live in Santa Clara and Alameda counties, but none of the five major bilingual Korean community groups in these areas that AsAmNews contacted knew about Market Match. This was the case even if the organizations assisted food-insecure Koreans with CalFresh navigation, food banks, on-site meals, food delivery, or reduced-price, health-conscious meals.

No county for old Koreans in the Bay Area

The Korean population receiving CalFresh in Santa Clara County, where 44% of the Bay Area’s Koreans live, has nearly tripled from 361 in 2016 to 1,025 in the present.

But Lindsay Torres, of the Pacific Coast Farmers’ Market Association (PCFMA), working at the table of the V.A. Palo Alto Farmers’ Market, said that she had seen plenty of Chinese, Vietnamese, and Filipino shoppers, especially at locations in Milpitas and Union City locations, but not Koreans.

A sign at a farmers’ market in Palo Alto beseeches people to help save Market Match.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Printed materials neatly arranged in front of Torres were mostly in English; some items had a few lines in Spanish, Chinese and Russian.

She said that PCFMA obtains census data at existing and prospective market locations, but mostly to gauge the marketability of new vendors.

Asian vendors, such as Hmong farmers and South Asian hot food purveyors, attracted and assisted people who spoke their languages. But Market Match employees were mostly monolingual English speakers. Like herself, anyone bilingual spoke Spanish, with the exception of a Southeast Asian colleague.

Torres said she hoped that her employers would hire more speakers of Asian and other languages to accommodate underserved non-English speakers.

Lee Woong Song, Chairman of the Board at the Oakland & East Bay Korean American Association (OEBKAA), said that he had heard of low-income Koreans shopping at the Old Oakland Farmers’ Market on 9th and Broadway.

Asian shoppers swarmed the stands at the Friday market in mid-May. Especially popular was the station of Kay Lee Farms, where scallions, yams, and cholesterol and hypertension-reducing bitter melon leaf beckoned in heaps.

“Coming from Fresno, we always try to bring variety. But, yes, our customer base is mostly Asian,” said Paul Lee, who works the farmland with his brother Chang and their mother Kay.

From left to right, Bangladeshi American Dorothy Paul with brothers Paul and Chang Lee of Kay Lee Farms.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

The Lees, who travel for hours weekly to markets in Oakland and Temescal, said that their Oakland customers were primarily Chinese, while their Temescal customers tended to be White. Either way, Koreans were a rare sight.

“The few Korean people I ran into were reluctant to seek help,” Paul tentatively offered, before rushing to assist customers and drop more bright green Market Match coins and bills into an organizer.

The compartment for the coins was as full as the one for bills. The Lee brothers said that they want Market Match to stay alive – 40% of their revenue comes from EBT consumers, and half of that is from the Match.

Their extra 20% in sales now hanging in the balance is part of $19.4 million in total Market Match revenues enjoyed by local farmers throughout the state in 2023.

Shoppers at Kay Lee Farms stand at the Old Oakland Farmers’ Market.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Produce from Kay Lee Farms, owned and operated by Hmong Americans in Fresno.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Market Match determined to survive

In a video conversation with AsAmNews prior to the state budget’s restoration of Market Match funding, Assem. Phil Ting, (D-San Francisco) said he was hopeful about the program’s survival.

The representative, who wrote Market Match into law by creating the California Nutrition Incentives Program (CNIP) in 2016, said the proposed cuts would hurt too many people to make it worth the savings to the state’s budget.

The expansive consortium of stakeholders defending the program is asking the public to write directly to the governor, email legislators and budget leaders, post on social media, and tag state representatives, budget leaders, and senatorial staffers to advocate for the benefits before the budget’s ultimate finalization.

Ecology Center is applying for federal matching funds on its own after the agricultural department neglected to seek it this year and is working busily with various partners to raise reserves to keep Market Match going in case the worst still happens. The organization also paused its hiring and told partner markets to reduce their matching amounts for shoppers by $5 starting July 1.

Assemblymember Ting, though a staunch advocate of the program with many supporters in the legislature, is terming out of his post this November.

Looking ahead, Tamborello said, “We as advocates need to do a better job of educating new classes of legislators on the value of programs that help both California farmers and low-income residents.”

This project is supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.