'Forcing people to work for free': Ohio AI start-up sued for wage theft scheme

The story was originally published in The Cincinnati Enquirer with support from our 2024 National Fellowship.

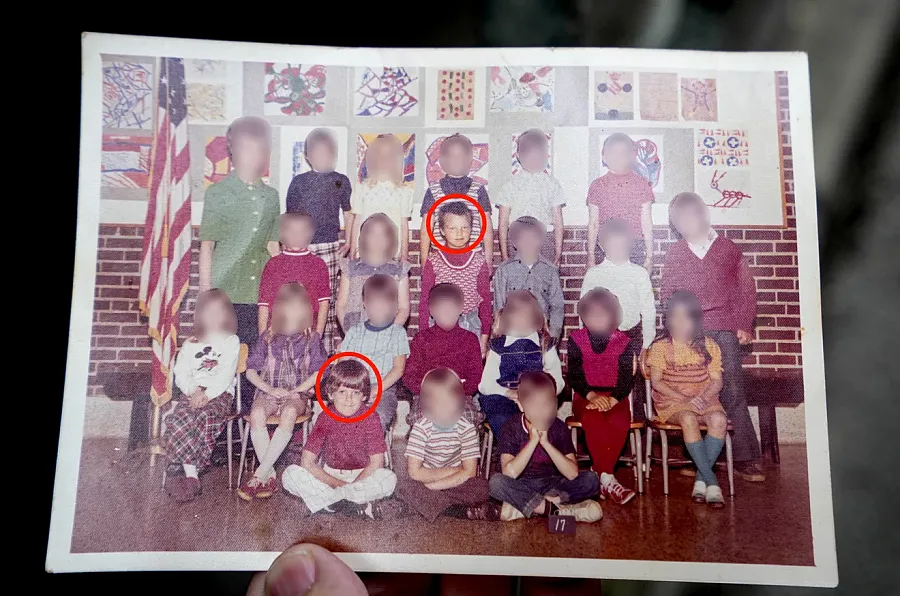

Bill Nostheide, Bill Haynes and Don Wright worked together at Clarigent Health before Nostheide sued the latter two over fraud and unpaid wages.

Provided By Bill Nostheide

A month after his wife died in 2022, Bill Nostheide received a Venmo request for $200,000.

“I hate to ask this,” read the message from Nostheide’s friend and boss at the time, Don Wright. “But could I borrow $200,000? I promise that I will pay it back.”

It wasn’t the first time Wright had asked Nostheide for money. Wright’s excuses ranged from being stranded at the airport to being too “broke” to cover his son’s tuition. Mostly, though, Wright blamed Clarigent Health, the AI suicide prevention company he founded – and where Nostheide worked – for his financial troubles.

Nostheide didn’t give Wright the money that time. But other times, he did. The two were inseparable from Cub Scouts to college, so Nostheide trusted Wright’s promises to pay him back. Plus, Nostheide believed in the AI-driven app that Clarigent was developing to determine whether teens might be at risk of suicide.

“I thought we were gonna make a difference,” said Nostheide.

Instead, Nostheide is now ensnared in a legal fight over the demise of a company that once seemed so promising that it attracted millions of dollars from investors and taxpayer-funded grants.

Though Clarigent Health shut down earlier this year, Nostheide is taking Clarigent, Wright and Bill Haynes, the company’s chief technology officer, to federal court. Nostheide is suing all defendants for unlawful retaliation and Wright for fraud and wage theft.

Between unpaid wages and the loan, as well as interest on the money that Nostheide himself borrowed to be able to lend Wright money, he says he’s out roughly $500,000.

In a response to an email from The Enquirer, Wright emphatically denied the allegations. Haynes, through his lawyer, did the same.

“We do deny that there was any grant money misuse or any unlawful activities,” said Wright, who declined to answer other questions due to ongoing litigation. “Everyone at Clarigent was dedicated to trying to slow the growing problem of suicide.”

But behind the scenes, the company’s finances were a mess. According to Nostheide, employees hadn’t been paid for at least six months by the end of 2023. What started out as a one-time payment in May 2022 ballooned to a loan of nearly a quarter-million dollars, and Nostheide began to worry that he’d never get his money back.

“It was just supposed to be a short term thing,” recalled Nostheide. “He just kept asking for more.”

Don Wright, pictured on the left, and Bill Nostheide, in the center, attended the same schools from kindergarten to college.

Phil Didion/The Enquirer

‘Measure your mental health in 5 minutes’

Two months after an Enquirer investigation found that schools and county social workers had no evidence proving that Clarigent’s suicide prevention AI helped them prevent youth suicide, Clarigent Health vacated its office in Mason and disconnected its website.

Hamilton County Juvenile Court's social workers tried to use the Clairity app to detect suicidal teens, but ran into numerous technical issues and ended up discontinuing its contract with the company.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

But before it shut down, Clarigent’s AI-driven app, known as Clairity, was once seen as the future of youth suicide prevention. Developed at Cincinnati Children’s, Clairity was backed by nearly a million dollars in grants from the National Institutes of Health, through a grant issued in 2021, followed by another one issued in 2023.

Clarigent claimed that Clairity could “measure your mental health in five minutes.” Even before its product launch in October 2020, the boldness of the company’s vision attracted investors from venture capital firms such as CincyTech and Columbus-based Rev1 Ventures.

CincyTech chipped in at least $900,000 – with $280,000 of that coming from the Ohio Department of Development, according to a spokesperson from the department. Rev1 Ventures invested another $350,000, according to a spokesperson.

A total of $4.5 million was invested into Clarigent before Clairity hit the market, said Mike Venerable, former CEO of CincyTech, at a 2023 panel hosted by Cincinnati Children’s, though it’s unclear how much of that money came from CincyTech.

Clarigent’s success was widely anticipated, in part due to its credentialed and well-connected founder, Don Wright. In 2016, Wright and his colleagues sold Assurex Health, a company he cofounded, for $225 million to a Salt Lake City-based genetics company.It’s not clear how much money Wright received from the sale.

Similarly to Clarigent, Assurex was built around a singular product developed at Cincinnati Children’s: a test that analyzed a patient’s genes to determine which medications would work best for their mental health disorder.

Wright held influential board positions locally – tech hubs at the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s among them – as well as others that held national sway. In 2023, Wright served as both the executive chairman of a precision medicine company based in Canada and as treasurer for the DC-based nonprofit, the American Association of Suicidology.

Wright’s passion for suicide prevention was driven, in part, by a family tragedy.

“I have a son who died by suicide,” said Wright in his response to The Enquirer’s questions. “Anyone that questions our commitment or asserts that we were not 100% focused on this problem is simply wrong.”

For 6 months to a year, employees worked without pay

For the first three years that Nostheide worked at Clarigent, pay wasn't a problem. It was in May 2022 that Clarigent first began missing payroll, the same month that Wright first asked Nostheide for money, according to court documents. The payroll issues persisted for three months.

Bill Nostheide stands outside of the federal courthouse where he filed his lawsuit against Clarigent Health, CEO Don Wright and CTO Bill Haynes.

Phil Didion/The Enquirer

Then, from February to December the following year, Nostheide says that Clarigent didn’t pay him at all, save for three paychecks that amounted to less than a full month’s pay. Each check only arrived after he confronted Wright about it, according to Nostheide.

“People were complaining that they still weren't getting paid,” Nostheide said. He shared text messages with The Enquirer showing that he and other former employees communicated about their missing paychecks.

“They kept making us feel like if we didn’t work, we weren’t gonna get any of our back pay,” said Nostheide.

Still, by mid-2023, employees hung onto hope that an incoming $460,000 grant from the NIH would help Clarigent catch up on payroll.

“So we kept working,” said Nostheide, “thinking we were going to get paid back.”

But once the grant arrived in August, employees only received one paycheck, according to Nostheide. “None of us know where any of the money went,” he said.

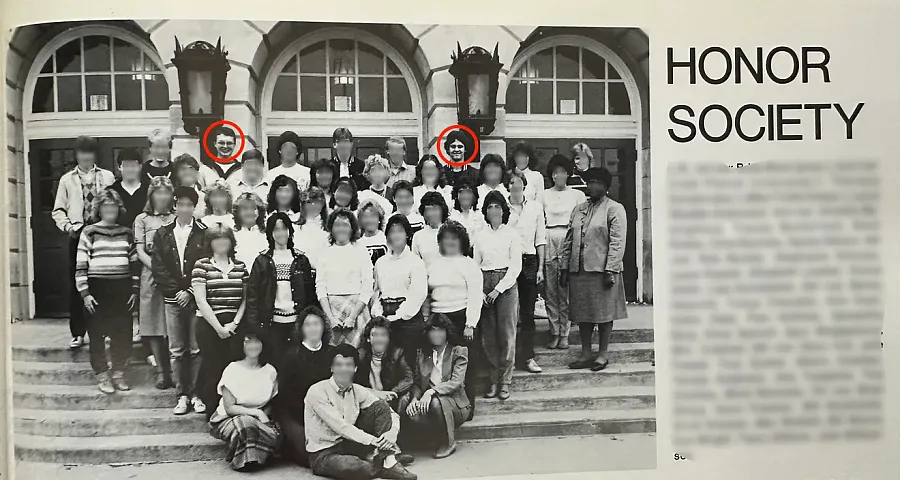

Bill Nostheide, on the left, and Don Wright, on the right, were in Western Hills High School's honor society together. Now, Nostheide is suing Wright for wage theft and fraud.

Provided By Bill Nostheide

Who was in charge of Clarigent’s money?

Beyond Clarigent’s C-suite, it is unclear whose job it was to ensure that Clarigent’s money was used properly.

According to Nostheide, CincyTech sent former executive Matt Storer to attend onsite meetings in Clarigent’s office.

“Matt knew that Clarigent was not paying his employees minimum wage, which is required by federal law,” said Nostheide. Neither Storer nor CincyTech responded to The Enquirer’s emails about the claim.

As quality assurance and compliance officer, Nostheide says it was his job to make sure Clarigent’s grant money was spent properly, but that he, along with other employees, was prevented from doing so.

“Don and Bill would not let any of us see where any of the money went,” said Nostheide. “They kept it all very secret.”

Records from the Warren County Auditor's Office website show that two and a half weeks after Clarigent received its second NIH grant in August 2023, Wright paid property taxes for his house and adjoining property in Morrow, amounting to nearly $9,000. The taxes were due the month prior, according to the auditor's website.

“He paid more on his property taxes than any of us got for our paychecks,” said Nostheide.

Wright called the allegation that he used NIH money to pay his property taxes “ridiculous and fraudulent.”

“The NIH grant money was used to pay for NIH grant activities,” he said.

The Enquirer reached out to both the public and private entities who funded Clarigent Health to ask whether the company spent their money.

Cincinnati Children’s declined to address the lawsuit directly.

A CincyTech spokeswoman declined to answer questions about the firm's involvement with Clarigent, citing the ongoing litigation. CEO Emma Off's biography on the CincyTech website listed her as a Clarigent board member as of July 29. After this story published, Off clarified she was on the board from March 2024 to February 2025. Nostheide was fired in January 2024.

Thomas Buckley, a spokesperson for the NIH, also declined to answer questions about what the agency knows about how Clarigent used the nearly $1 million dollars in grant funding.

“NIH is committed to ensuring the proper stewardship of taxpayer dollars and oversight of the projects it supports,” said Buckley, referring The Enquirer to its grants compliance and oversight policy. “NIH requires all recipients to submit regular progress reports on the status of their research.”

‘I really believed in it’

“They kept making us feel like if we didn’t work, we weren’t gonna get any of our back pay,” said Nostheide, of Clarigent leadership.

Phil Didion/The Enquirer

Nostheide’s wife died in September 2022, on a day that Wright asked Nostheide for $8,000 in cash – his second time asking for money that month.

“Instead of being at the hospital, he wanted me to go to the bank again,” recalled Nostheide, who says his wife would have “smacked” him if she knew how much money he’d lent Wright before and after her death.

Months after Clarigent received the NIH grant, full-time employees lost their health insurance. Employees including the senior engineer, head data scientist and clinical project manager left the company soon afterwards, leaving behind a skeleton crew.

Then, when Nostheide told Wright that he was considering legal action against Clarigent, Wright fired him. “I got fired from a job that I was paying to work at,” Nostheide joked.

But he still thinks Clarigent’s software was something special.

“After my wife died,” said Nostheide, “It was showing that I was suicidal and depressed.”

“I really believed in it.”