Girl's death among 500 in one year in community care

Christen Shermaine Hope Gordon was one of 500 patients in 2013 who died in community care while under the auspices of the Georgia Dept. of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities. While the community placements were halted, parents are worried the state is about to resume the program. This is the first in a series.

Tom Corwin wrote this article, originally published by The Augusta Chronicle, as a 2014 National Health Journalism Fellow.

This story was written by Tom Corwin and Sandy Hodson and originally published by The Augusta Chronicle.

WRENS, Ga. — Months after her daughter died, LaTasha Gordon’s voice still shook with quiet fury as she talked about questions she still has about why her severely developmentally delayed child died in state-sponsored community care.

“I want justice because I want to know what happened,” Gordon said. “Because they weren’t taking care of her the way they were supposed to.”

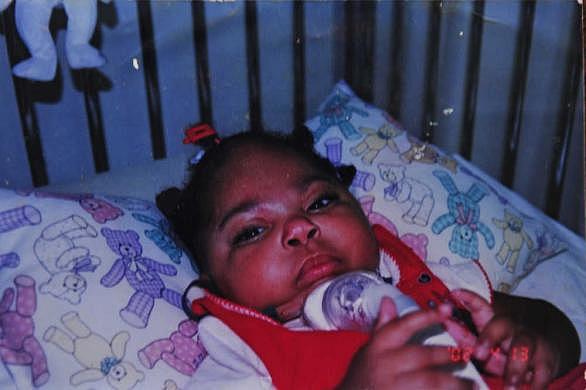

Christen Shermaine Hope Gordon was one of 500 patients in 2013 who died in community care while under the auspices of the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities. The 12-year-old was one of 82 classified as unexpected deaths, including 68 who, like her, were developmentally disabled. In 2014, an additional 498 patients who were receiving community care died, including 141 considered unexpected.

Despite her mother’s objections, Christen was also one of more than 499, as of January, moved from department facilities to community providers such as group homes under a 2010 settlement with the U.S. Justice Department over the conditions in the state hospitals. Christen is one of 62 of those transfers who have subsequently died.

Faced with mounting evidence, including a rash of deaths, the state agreed to suspend the wholesale transfer of patients out of state hospitals into the community in 2013, subsequently fired a handful of providers and began to reassess how it was doing its community placements.

Late last year, a state official said the department would restart community placements for the developmentally disabled in the region surrounding Augusta with the Pioneer Pilot Project. That worries some parents at the Gracewood wing of East Central Georgia Hospital in Augusta, who aren’t convinced the state can take those patients – many of whom need round-the-clock care – and provide a safe environment.

Pulling through

Deaths such as Christen’s should give them pause, said Gordon, who is still waiting for answers about how and why her daughter died.

Christen was born two months premature at the Medical Center of Central Georgia in Macon on March 13, 2001, and from the beginning there were problems. She was delivered in an emergency Cesarean section and weighed only 3 pounds, 5 ounces. When Gordon awoke from the surgery, she learned that Christen’s hips were dislocated, she had club feet, and she had only three of the normal four chambers in her heart.

“They wanted to (do surgery) but they didn’t do it because she was so small,” Gordon said. She was told Christen wouldn’t survive, and eventually the girl was transferred to the James B. Craig Nursing Center at Central State Hospital in Milledgeville to await the inevitable.

But she didn’t die.

“She thrived,” said Fay Smith, her special education teacher for six years. “She was a beautiful little girl.”

“When she was at Craig, she was happy, she always played with her toys,” Gordon said. “She loved the little toys they made.”

Christen never spoke, never walked on her own, had to be fed through a tube, bathed and toileted. But there was a spark there.

“She was very active,” Smith said. “If you put her down on the mat, she enjoyed being on the mat.”

Smith would set Christen up in a special desk on the mat and, in her own way, she would communicate back, with gestures, smiles and sounds.

As part of the settlement with the Justice Department, Georgia was to move out 150 patients per year from the state hospitals into community care, and Christen came under that order to move in 2012, despite her mother’s strong protests.

The center had tried to move her 10 years earlier to a home in Warner Robins, “but I didn’t let them,” Gordon said. “Then they had other families afterwards and I was still against it. I felt she got the best care where she was.”

According to the settlement agreement, moves into the community are supposed to be voluntary, but that did not seem to matter in Christen’s case. The plans moved forward and Smith felt uncomfortable with the provider, ResCare, and the host home subcontractor where the provider was going to place Christen in Macon. The host home family, Fred and Juliet Ssenjakko, were both nurses.

“Nice family, nice home,” Smith said. “It was supposed to be the most ideal thing you could have asked for.”

But the family had trouble making the transition meetings with the staff at Craig to go over how to provide care for Christen, she said.

“They would not come on a regular basis,” Smith said. “The provider would come. Sometimes the host mom would come. Sometimes the host dad would come. And sometimes neither one.”

Even though he was the host home provider responsible for Christen’s care in the 15 months she lived in his home, Gordon said she never met Fred Ssenjakko. He did not return a call seeking comment.

‘Didn’t feel right’

It seemed in the months leading up to Christen leaving in May 2012 that the deadline was more important, Smith said.

“It just didn’t feel right then,” she said. “There was such a hurry, hurry, trying to get her out.”

Smith, who has since left Craig, tried to keep up with Christen after she was moved to the host home and finally managed to help Gordon, who had transportation issues and difficulty getting from her home in Wrens to Macon, visit Christen about two months later in July.

The minute they walked into the den where Christen sat, she lit up, Smith said.

“She wasn’t verbal but she rocked herself back and forth, back and forth when she heard our voices,” Smith said. “She called out to both of us when she recognized our voices.”

Smith noticed something odd about how Christen was dressed – she had a long pink stocking on her left leg but there was only a little sock on the right foot. When Smith touched the left leg, she felt a cast underneath.

“LaTasha said something to the effect of, ‘My baby’s leg is broken. What happened?” Smith said.

The girl had been hospitalized in Macon for an impacted bowel and a twisted colon a month after being moved to the home, according to a state investigation obtained byThe Augusta Chronicle. During the night she had fallen out of bed and broken the leg, according to the state investigation.

“(Juliet) said she thought the hospital had called to let me know she had broken her leg,” Gordon said. “I don’t know what happened. She can’t walk. She can’t lift herself.”

That incident brought to light another key difference from her care at Craig.

Whenever anyone was hospitalized, someone at the center stayed with them the whole time, Smith said. But the state investigation shows Christen fell out of bed after Fred Ssenjakko left her in the hospital to go home and take a shower. When the hospital called ResCare to tell them, ResCare Executive Director Peggy Clay called and asked him to return to the hospital, which he did but then left because he was not being paid to do it, according to the state investigation.

He only returned when Clay, who is no longer with the company, said she was giving him 30 days’ notice that she was terminating his services, according to the state investigation report.

Poor communication

Perhaps the most glaring issue revolved around providing Christen with the proper level of care.

When she left Craig, Christen’s Individualized Support Plan called for 24-hour care seven days a week by “awake staff,” according to the investigation. But ResCare said the Ssenjakkos were not required to give 24-hour care until after the broken leg incident when the “exceptional service rate increased,” primarily because the host family “complained that Christen kept them awake at night.”

Christen needed the “awake staff” monitoring because she awoke every one to two hours, according to the state investigation, and she was fed every four hours.

“She cannot be left alone with a monitor or she will injury (sic) herself,” the report noted. One of the people providing case management services for Christen told the state investigator that she “believes the Ssenjakkos may have relied on the baby monitor rather that (sic) providing 24-hour awake staff, but they have not admitted it to her,” according to the report.

Fred Ssenjakko told the state investigator that “ResCare never provided staff they promised to assist with Christen when he was told Christen required 24-hour awake staff,” according to the report. He also told the investigator that the two care providers were not paid enough to provide the awake care.

ResCare said it made clear to the Ssenjakkos that they were responsible for providing that care but did not explain how it is possible for two people to do that. Fred Ssenjakko also worked at another job outside the home, and on the morning Christen died, his wife frantically called him but he could not leave work, according to the investigation.

Gordon was not called about the first hospitalization, or a visit to the emergency room the following December when Christen had the flu, or when she had wisdom teeth removed the following February or for any of the 20 doctors’ visits in the 15 months the Ssenjakkos had her.

The call she did get from them was in July 2013, when Christen was back in the hospital after losing five pounds, about 10 percent of her weight, the month before.

When Gordon got to the hospital in Macon and saw Christen, she was shocked.

“She was skin and bones,” Gordon said. Smith, who was with Gordon, tried to question Juliet Ssenjakko about it and was told they had not realized how much weight she had lost. But Christen did not look to her at all like the little girl she had known at Craig.

“She was listless,” Smith said. “Her little eyes were just sad.”

Increased health issues

Gordon said she was told her daughter now had lupus and autoimmune hepatitis and that her body was now apparently attacking her liver. Christen was put on prednisolone, a corticosteroid, and when she was discharged after a week she had lost another five pounds, down to 40 pounds, almost 20 pounds less than she had weighed at Craig.

Christen’s feedings were increased, and she gained back five pounds in less than a month, while the dosage of her corticosteroid was decreased.

But on Aug. 16, Christen was flushed and crying and had a slight temperature, according to the state investigation. She was diagnosed the next day with an ear infection and prescribed a cephalosporin antibiotic.

The next day, Fred Ssenjakko noticed red streaks in Christen’s stool and was told by a doctor to monitor her bowel movements and come back for a follow-up in a week. Her temperature seemed to be elevated over the next couple of days, and she saw a nurse practitioner at a pediatric clinic “because she was lethargic and drooling more than usual,” according to the state report.

The nurse practitioner warned Juliet Ssenjakko that the red streaks were a side effect of the antibiotic and said she should limit the use of Tylenol to control fever because Christen’s liver enzymes were elevated. The next day, Christen’s stool turned black and a couple of days later black and red.

On Aug. 23, Fred Ssenjakko took Christen to a pediatrician and saw blood in a stool sample collected. Christen’s temperature was 103 degrees. He thought she was going to be hospitalized again but the physician consulted with the children’s hospital in Macon and decided against it.

A little after midnight Aug. 24, Juliet Ssenjakko told the state investigator, “Christen was restless and irritable but her temperature was normal,” according to the report. The girl was awake just before 5 a.m. when she was given a dose of ulcer medication and was covered with a blanket because “she felt cool,” she told the investigator.

Christen was fed at 6:30 and when Juliet checked on her at 7 a.m. she “was sweating but not in distress,” she told the investigator. After Fred Ssenjakko left for work, Juliet checked on Christen at 7:30 a.m. and as she entered the room, she said, Christen “raised herself on her elbow and fell over.”

She touched Christen and found she was breathing slowly. Juliet called her husband but he could not leave work, so she called another host home nurse nearby for help getting Christen to the emergency room.

When that nurse, Juliet Kazibwe, entered Christen’s room, the girl was lying on her bedroom floor and Juliet Ssenjakko was performing CPR. Kazibwe felt a faint pulse and took over CPR. The emergency medical services crew arrived and took over CPR while taking Christen back to MCCG.

Hospital staff declared Christen dead at 8:46 a.m.

Questions unanswered

Again, the Ssenjakkos did not call Gordon. Clay, of ResCare, told her Christen was dead. Gordon said she was told by someone with the state that Christen had died of aspiration from something that had backed up into her lungs.

When Gordon arrived at the hospital and asked for an autopsy, a woman there told her the coroner said an autopsy was not necessary and, when she insisted, that it would cost $3,000. It is actually state policy that if a patient dies in a host home, the provider is supposed to ask for the autopsy.

When another parent of a child at Craig offered to put up the money, the hospital said the coroner still refused, Gordon said.

Bibb County Deputy Coroner Lonnie Miley told the state investigator that he was notified by the hospital about Christen’s death and “did not find a need for an autopsy during his review of the death because she had a history of cerebral palsy, mental retardation, cardiac and respiratory complications and seizures.” He cited the preliminary cause of death as a heart attack.

A final cause of death had not been determined when the state investigator completed her report two months later. A nurse with the department told the state investigator that the steroid and over-the-counter painkillers Christen received could have caused liver failure. A database of Georgia deaths from 2013 lists her cause of death as cardiac arrest, with secondary causes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (which was not listed among her diagnoses in the state investigation) and seizure disorder.

Gordon said she never could get Clay from ResCare on the phone again. At the time of the investigation, ResCare, a for-profit provider, had 91 patients with developmental disabilities and 45 host homes in Georgia like the ones in Macon.

“After she died, I didn’t hear from anyone from ResCare,” Gordon said. “I didn’t hear from (anyone) with the state. When they put her in the people’s home, the state made a lot of promises about they were going to help do this, they were going to do that. After they placed her, I didn’t hear from no one.”

All she has left is one question: “Why she died,” Gordon said.

While the state investigator was trying to complete her report in the month after Christen’s death, she spoke again with Clay, who was getting ready to place “another medically fragile child” with the Ssenjakko host home, according to the investigation.

How we did it

The Augusta Chronicle began looking into patients of the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities who died while in community care after learning of the death of 12-year-old Christen Gordon in August 2013.

The investigation began in earnest after the project was selected in 2014 for a National Health Journalism Fellowship, a program at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

The Chronicle used several Open Records Act requests to obtain investigative files on some of the 82 unexplained deaths in 2013 among the department’s patients in community care, which was then focused on just those with developmental disabilities.

The Chronicle received investigative files on 28 patients, but they were heavily redacted and did not contain names or other identifying information. The newspaper then obtained a database of all deaths in Georgia in 2013 – more than 76,000 – and after extensive cleaning of those records was able to use it to identify 24 of those patients. Using other databases, The Chronicle identified family members for a majority of those patients. Many were uninterested in pursuing an investigation into the deaths and some didn’t return e-mails or phone calls.

The Chronicle used other Open Records Act requests to discover that nearly 1,000 patients had died in community care in the past two years and that a majority of the unexpected deaths are among patients with developmental disabilities.

Photo Credit: JON MICHAEL SULLIVAN/STAFF

Read more about how The Augusta Chronicle reported this series here:

A look at 'unexpected' deaths in community care homes