‘Going up against more money than God’

Globeville, CO, residents who won a legal battle 20-years ago against the owner of a smelter that polluted their neighborhoods are still waiting for the clean-up to be completed.

Cara DeGette produced this story for Colorado Public News as part of a 2012 National Health Journalism Fellowship. Other parts of this series can be found here:

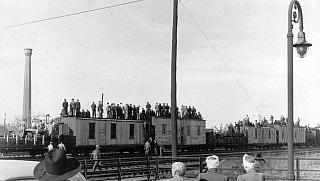

The last time – possibly the only time – that Globeville became a destination for people living all over Denver was Feb. 26, 1950.

That was the day that the biggest crowd in Denver’s history so far – 100,000 strong – made their way to the north side of town to watch the giant, 350-foot Grant Smelter smokestack dynamited to smithereens.

“All Denver was there – young and old, rich and destitute, pregnant women, mothers nursing babies in the windblown fields, families with cameras,” went one report in the Rocky Mountain News. The Rocky, as did the Denver Post, devoted pages and pages to the violent death of the landmark. KOA broadcast it live on the radio. Airplanes buzzed overhead. It caused, police said, the worst traffic jam in the city’s history.

The drama of 63 years ago became, according to another account, the “zaniest, if not most awesome spectacle in history … It also fomented the greatest mass display of emotion – joy, irritation, anger and sadness – which the city has ever known.”

The Grant smokestack, next to the giant Globe smelter, had been unused for 43 years. It was cracked and had been deemed dangerous. But blasting it down proved harder than thought.

A first, failed attempt left half the landmark, built of three million bricks, still standing. The crowd had a grand old time laughing at the antics of Denver Mayor Quigg “Smokestack” Newton and city Improvements Manager Thomas P. “Dynamite” Campbell as they brushed white dust from each others’ coats. They glared, powderfaced, at “Generalissimo” Omar Schultz, the blasting expert who had been imported from Salt Lake City to do the job.

“No down, no dough,” Campbell shouted at Schultz. After 15 minutes, most of the rest of the smokestack tumbled down in wind and a sudden rumble, to the shock and laughter and tears of the throngs who were watching.

“You know,” one man said to his son as they left, “I’m glad you got to see this. It was the greatest thing Denver ever did. But now that it’s done, I wish they had made a monument of the chimney.”

Eight years after that historic moment, highway planners began to cut Globeville away from the rest of the city. In 1958, Interstate 25 bisected the neighborhood north to south. Six years later, Interstate 70 was rammed through the east to west middle of Globeville. Travelers zipping along I-70 to Denver International Airport to the east, and to the mountains to the west, may never notice residents living in one of the most historic areas of Denver right below.

They probably don’t realize that they are passing what used to be the largest smelter in North America, one of 23 proposed federal Superfund cleanup sites in Colorado. They probably don’t know that Asarco, the multinational company that owned the smelter, was forced by three separate lawsuits to clean up the 75-acre smelter site and the contaminated neighborhood it left behind.

Over the years the riches produced at the smelter came from gold and silver, lead and arsenic. Cadmium, used as protective coatings for steel and iron, was lucrative during the last century.

The Environmental Protection Agency explains what all those toxins left behind can do: “People can be exposed to contaminants by swallowing contaminated soil or by inhaling the dust. Exposure can potentially cause cancers, such as skin cancer. Possible non-carcinogenic effects from exposure over long periods of time include damage to the central nervous system, reproductive system, kidneys, and digestive tract.”

In 1983, the Colorado Department of Health and Environment sued Asarco for damages to the natural resources, mostly for contamination of groundwater. Testing showed the company was polluting the land, air, surface water, groundwater, soils and sediment. Five years later, the health department and Asarco reached an agreement to study the extent of the contamination.

By 1989, when attorney Macon Cowles got involved, the health department had posted fliers around the neighborhood, warning resident gardeners to mix homegrown veggies with those bought at the store. The idea was to dilute the potential heavy metal content in their diet.

“We immediately thought about the health impacts,” says Cowles, who filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of the neighbors. But, proving the smelter was causing cancer for people living in Globeville was a difficult, not to mention expensive, proposition. Overall, one in three people develops some type of cancer, Cowles noted.

The socioeconomic realities of the working class community further complicated things. People who live in more affluent neighborhoods, with better access to healthcare and who exercise regularly, are generally healthier. In Globeville, a higher percentage of the population smoked, and also, due to their general diet, were often at higher risk of diabetes.

“In the end we decided we couldn’t bring in health [issues] because there was a likelihood we could lose,” he says.

Instead, the class action suit was focused on forcing Asarco to clean up the toxins in the soil at 657 homes around the smelter. The company would also be required to pay homeowners and renters cash settlements, and to provide restitution to residents from a contaminated housing project next to the smelter.

Through the trial, Cowles said the judge would not allow any references to environmental racism, a term used to describe the targeting – intentional or not – of industrial operations on low-income and minorities. But Cowles made sure that his clients appeared in court every day during the eight-week trial. Jurors could not miss seeing the working class faces of the community. On the day of closing arguments, a cold February day in 1993, an astonishing thing occurred.

Cowles’ wife, Regina Cowles, describes what happened: The plaintiffs had been instructed to show up early, and the courtroom was packed. Many of them were in wheelchairs and using crutches. The corporate legal defense team and their clients arrived. Many were wearing full-length mink coats. With no seats to be had, there they stood in the courtroom, in all their splendor, while the lawyers laid out their final bids for justice.

“It was really one of the most – arrogant isn’t even the word for it,” Regina Cowles says. “The jury got it; they got it.”

They awarded $28 million to the residents, at the time the largest settlement ever won by citizens against a major corporation. Over the next four years, Asarco was forced to remove 12 to 18 inches of polluted topsoil from the homes in Globeville, and replace it with fresh dirt from southeast Colorado. “They called it ‘Escamilla soil’, which was pretty cool,” says Margaret Escamilla.

Margaret and her husband Robert Escamilla were the lead plaintiffs in the suit. A fourth generation Globevilleite, Robert is a retired master mechanic with the Regional Transportation District. Margaret has for years doggedly worked to improve their community, including as the former president of the neighborhood association.

They raised their two children in Globeville, in a comfortable, beautifully decorated home on Lincoln Street. Their daughter Juay, is grown and married and moved away. In 2003, their son Joaquin died, when he was 30 years old. He had a brain tumor – the same type of cancer that took Teddy Kennedy, the Escamillas say. “Cause unknown,” Robert says.

Side by side on a couch in their living room, the Escamillas finish each others’ sentences, their thoughts, as they relive the details of the lawsuit, won 20 years ago this month.

“I didn’t think we’d win, I mean, we were going up against more money than God,” says Robert. “It was like if Haiti went to war against the United States.”

For Robert, it was never a question about whether the neighborhood was contaminated, but how badly it was contaminated. As a boy, he played in the dirt where Asarco dumped its waste; he watched open train cars of lime cadmium rattle through the neighborhood. Still, the Escamillas knew how explosive it would be, to challenge the biggest and most powerful employer in the neighborhood, and also risk the stigma of contamination.

“The community was divided over this lawsuit, to say the least,” said Cowles, the attorney. “The ones who wanted to stand firm were ostracized by their neighbors.”

“If we would have lost this lawsuit, all hell would have broken loose,” Robert Escamilla says. The win allowed the neighborhood to unite, and see the justice of having their properties cleaned of contaminants, with money to reinvest in their homes.

A third lawsuit forced the company to pay to clean up additional residential properties, on the south side of I-70. And, six months after the Escamilla suit was won in 1993, the state of Colorado succeeded in its legal battle to force Asarco to clean up the 75-acre smelter site itself, which had been proposed as a federal Superfund site. “It was, says Cowles, “a very exciting period for Globeville.”

Then, in 2005, Asarco declared bankruptcy, and announced it was closing the smelter, which had diminished to a tiny operation. Ultimately, the judge ordered Asarco to pay $16.5 million to complete the cleanup.

The good news, says Fonda Apostolopoulos, of the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, the money for the cleanup was guaranteed, and held in trust. The bad news, it slowed down the timeline for completion. Current projections are now at least 2015.

“We’re talking two-and-a-half to three years to clean up the property, and then we can talk about building on top of it,” says Apostolopoulos. And then, the state will need to get a final signoff from the Environmental Protection Agency. “Nothing,” Apostolopoulos says, “happens quickly with the EPA.”

The cleanup is being done by EFG-Brownfield Partners, a Denver-based urban infill developer. In simple terms, the massive project comes down to stabilizing the soils and building trenches to contain the contaminated groundwater. Some 50 structures have all been demolished. Eventually the entire site will be capped with a mixture of molasses and alcohol – a process that is being used increasingly at polluted sites to help neutralize heavy metals.

One problem – and it is one that won’t likely be immediately fixed – is the plume of contaminated groundwater, which includes elevated levels of cadmium. The plume seeps from the former smelter for nearly a mile before dumping into to the South Platte River, a major water source.

The federal Clean Water Act allows for five parts per billion of cadmium. Between 2006 and 2010, the average levels were 15 parts per billion – three times higher than what is allowed. But that figure is, Apostolopoulos says, far lower than the 100 parts per million that was recorded in the past. And 100 yards downstream, the contaminants dissipate to acceptable levels, he says.

The cleanup of the former smelter property will further slow down those high levels of cadmium from pluming down to the river, Apostolopoulos says. The current plan is that somewhere between 30 and 100 years, Mother Nature will flush the system out.

“We’re monitoring it. We know that people can’t have groundwater wells [in the area], and we’ll let nature take its course,” he says.

It’s not yet clear what exactly what will eventually be built, once the 75 acres are capped. A 2010 cooperative agreement between the Denver Urban Renewal Authority and Adams County – where 80 percent of the property lies – calls for a “Globeville Commerce Center.” Such a center, DURA announced, would potentially include 1.1 million square feet of commercial space and create hundreds of jobs.

But technically, right now the property is zoned to allow heavy industrial use. That’s a nightmare scenario for community activists like the Escamillas, and for the current president of the neighborhood association, Dave Oletski.

Apostolopoulos insists that bringing some new heavy-polluting site into the neighborhood simply will not happen. “We’re not going to spend millions of dollars for someone else to come in and recontaminate this site,” he says.

Still, Oletski and others wonder why the 75 acres can’t be cleaned enough to allow for a mixed-use development, which could potentially blend urban residential living with commercial space. Imagine, he says, having a grocery store, even a pharmacy, in Globeville.

Apostolopoulos whips out his calculator and does the math, figuring what it would cost to remove a tiny portion – just five acres of the most highly contaminated soil, and make it clean enough for human habitation. Total cost: $72.6 million. And that’s not counting the 140-mile round trips to truck the contaminated dirt to a site that would take it. Add that, and that five-acre cleanup, out of 75 acres total, would be somewhere in the ballpark of $150 to $200 million. “The cost,” he says, “would be astronomical.”

“There’s a lot of problems in the area, and I can’t solve all of them,” Apostolopoulos says. “But I can at least help them with this eyesore.”

For the Escamillas, the lawsuit is long behind them. Their three backyard gardens are filled with clean dirt, and there is an end – maybe not in sight, but close – to the cleanup of the smelter. But one question cannot be avoided: What’s that smell? That smell in the neighborhood?

“I was hoping that wouldn’t come up,” says Robert Escamilla.

This story was originally published in The Colorado Public News on January 22, 2013

Photo Credit: Western History/Genealogy Dept., Denver Public Library