‘The Great Hurt’: Facing the trauma of Indian boarding schools

Mary Annette Pember wrote this article for Indian Country Today Media Network as a 2014 National Health Journalism Fellow.

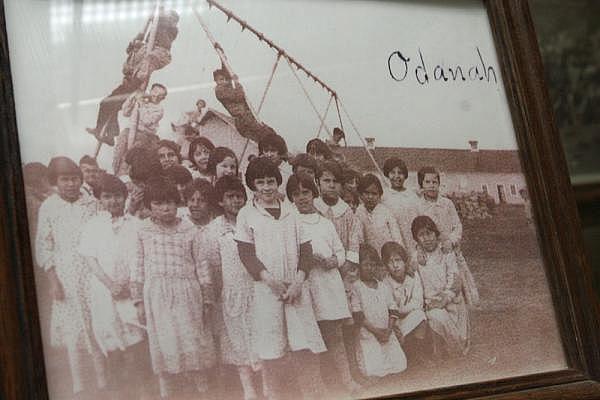

Old photo of children at St. Mary’s Indian boarding school. Mary Annette Pember

“Aww, here we go again, talking about the dang boarding schools!”

This was the first thought Chally Topping-Thompson had when the topic came up in her social work class at St. Scholastica College in Duluth. Topping-Thompson of the Red Cliff Band of Ojibwe had heard hushed talk about the bad times at Indian boarding schools all her life. The talk, however, was for her, part of a long ago past of trouble and hurt. Struggling to raise a child and finish her degree in social work, however, she had more immediate problems of her own. “I thought the history of boarding schools didn’t really have any meaning for me or my generation,” she said.

The course, however, radically changed her perception about the impact of boarding schools on contemporary Native life in general and her own family in particular. She says the class was unlike any other she had attended. Rather than the typical college lectures and assigned readings, students learned parts of a reader’s theater play, The Great Hurt, and later performed the play for the public.

The Great Hurt was written by retired artist and St. Scholastica College faculty member Carl Gawboy of the Bois Forte Band of Minnesota Chippewa. It contains eyewitness accounts, both historic and contemporary, of the Indian boarding school experience. Performers read aloud the words of people such as Captain Richard Pratt, credited with founding the governing philosophy of the schools. Pratt famously championed the idea that the schools should “kill the Indian to save the man.”

Topping-Thompson said learning about the history of the schools and reading the play helped her better understand the experiences and actions of her family. Many of her family members were sent to boarding schools which she believes greatly contributed to her grandmother's alcoholism. Her grandmother, who attended Pipe Stone Indian school, was an alcoholic. She was unable to care for her children, so they were placed in non-Native foster homes. This angered Topping-Thompson, who blamed her Grandmother for being a poor mother.

“After the play, I was able to see and feel the pain of my grandmother’s experience. I came to understand how she never had her own needs met as a child and how this contributed to her being unable to nurture her own children, “ Topping-Thompson said.

Topping-Thompson was assigned to read the words of her Uncle Jim Northrup, a well-known Ojibwe poet and author from the Fond du Lac reservation whose work is included in the play. “I read his story in which he describes how the little boys would cry at night for their mothers in the dormitory. He said the crying would start with one boy, then move in waves through the children in their beds,” she said.

Gawboy wrote the play in 1972 while participating in a graduate internship. “No one wanted to hear about boarding schools back then so I threw the play in a drawer,” he recalls. Nearly forgotten, it languished in his desk for over 35 years.

A few years ago, his wife, Cynthia Donner, coordinator for tribal sites in the St. Scholastica Social Work Program, asked him if he had any suggestions for teaching students about historical trauma and the impact of boarding schools. He shared his long forgotten script with Donner and her colleagues, who immediately realized its value. Gawboy, Donner and Michelle Robertson, assistant professor of social work at St. Scholastica collaborated in updating the script.

“The Great Hurt brings history to life for students,” Donner said.

The play also helped social work students gain a greater understanding of how the impact of trauma, such as that experienced at boarding schools, can be passed down through the generations. “Researching the history of the schools and then participating in the play allows students to become directly involved in their own academic inquiry,“ says Donner.

Although the initial goal was to educate students and prepare them for work in the field, Gawboy and instructors in the Social Work Department soon realized that the play had potential that reached far beyond the classroom. They began receiving requests to perform the play in various Native communities in the region.

Native people wanted a way to talk about and process the grief and trauma from the boarding school experience.

The Great Hurt’s reputation has spread by word of mouth in Indian country. Gawboy, Donner and Robertson do not seek out venues for the play; they wait for communities to invite them and encourage people to create planning committees in order to determine how the play can best be presented in a way that is most beneficial. “People need to be ready to deal with historical trauma. Community members have to agree about how the play will be presented,” Donner said.

Some communities have opted to have a two-day workshop in which participants learn some information about historical trauma, how it expresses itself through the boarding school experience and then practice performing the readings. Typically, participants perform the play for the public immediately after the workshop.

Members of the Leech Lake reservation in Minnesota hosted the workshop and play as a collaboration between St. Scholastica and the Leech Lake Tribal College.

Students from both schools earned academic credits for attending an extended version of the workshop and later presenting the play for the community.

“The reality is that the U.S. has never acknowledged the trauma caused by the boarding schools. That made it harder for tribal communities to deal with the trauma and pain,” Donner said.

Gawboy and the instructors at St. Scholastica said that the play seems to take on the quality of ceremony when presented by Native people in their own community. “There is nothing greater than the power of story,” Donner noted. Members of the audience have often cried during the performance. “It was very emotional. People stood up [during the discussion period immediately following the play] and shared how that they’d never talked about their boarding school experiences, even with their families. It had just been too painful for them,” said Heather Craig Oldsen professor of Social Work at Briar Cliff University in Sioux City, Iowa.

Students and community members performed the play twice in Sioux City. “I still get goose bumps when I think of all the people who stood up with tears in their eyes,” Craig Oldsen said.

Non-Native people are also affected by the play. “The most common reaction from non-Natives is shock. They say that they never knew anything about this history,” said Gawboy.

There is growing awareness in Native communities that the high rates of suicide, depression and addiction are tied to unresolved trauma. “The Great Hurt offers a way for people to recognize and acknowledge the impact of historical trauma on their lives. For instance, one of the characters in the play, Carolyn Attneave, a social worker for a Native community guidance center in Oklahoma, describes the negative influences that boarding schools had on Native families. “I recall vividly how each year worried sets of parents would come to the clinic begging for help in securing placement in a boarding school for their 8 or 9 year old child. This puzzled me, and it soon became clear that although it was heartbreaking for them to part with their child they knew of nothing else to do. Neither they nor their own parents had ever known life in a family from the age they first entered school. The parents had no memories and no patterns to follow in rearing children except for the regimentation of mass sleeping and impersonal schedules they had known. How to raise children at home had become a mystery.”

Such dialogues provide an effective tool to bring people together to connect with something bigger than themselves, to see that trauma is more than their individual suffering,” Donner said.

Nitausha Williams agrees. A member of the Dakota Yankton Sioux Nation, Williams participated in the play while pursuing her degree in social work at Briar Cliff University. She described the experience as transformative. “I was raised with shame, anger, fear and isolation. The play helped me see how historical trauma was affecting my life,” said Williams who is a social worker with the Iowa Department of Social Services in Sioux City. She works as a tribal liaison ensuring that the state follows Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) policies.

She realized the cycle of abandonment in her family started generations ago. Williams, her mother and grandmother all attended boarding school and all abandoned their children. “We lost the bond and knowledge of family at boarding school. I see now how the behaviors such as the inability to show affection, the excessive cleaning were learned, “ Williams said. “I’ve made a whole lot of changes since that play. It has started a healing process for me,” she said.

Williams has decided that the trauma will stop with her. She makes a concerted effort to be affectionate with her children.

Many Native people who went to boarding schools have to relearn a connection to family, according to Williams. “At first my mother got angry when I asked her why she never hugged us or told us she loved us. But after awhile she apologized and now we hug. It’s uncomfortable for us but we’re getting better at it,” she said.

Since the play was performed in Sioux City, community organizations such as local tribal members and leaders, the police department, schools and department of Human Services created a collaborative to discuss the health and welfare of Native families according to Craig Oldsen. “The greatest impact, however, is that people are finally starting to talk about their boarding school experiences,” she said.

“The Great Hurt has helped us move towards healing.”

This story was originally published by Indian Country Today Media Network