Haitian Community Reeling with Fear and Anxiety at the Prospect of Losing Temporary Protected Status

The story was co-published with the Sacramento Observer as part of the 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

Volma Volcy oversees the crowd who were at the Capitol Building for a peaceful demonstration in opposition to Donald Trump’s immigration policies on July 17. Roberta Alvarado, OBSERVER

Under Donald Trump’s administration, immigration policy has taken a sharply restrictive turn, putting many immigrants at risk.

One of the most visible targets are Haitians with temporary protected status. The current legal order requires that Haitian immigrants with TPS protections remain shielded from deportation through Tuesday, Feb. 3, despite a July Department of Homeland Security rule that sought to end those protections on Sept. 2, six months before the previously published date.

On July 1, a federal judge in California blocked the premature termination and affirmed that TPS cannot end before the February deadline. Judge Brian M. Cogan found that DHS had failed to provide proper notice when shortening the 18-month TPS extension period granted by the Biden administration. The early termination would have abruptly ended the legal status of close to 350,000 Haitians, causing chaos and significant harm to those who relied on this protection, his ruling stated.

The administration already has escalated deportations to Haiti, including the removal of minors. On Sept. 10, six children ages 4-11 arrived in Cap-Haïtien as part of 132 deportees aboard the largest deportation flight yet since Trump returned to office, according to the Haitian Times. There have been four deportation flights to Haiti since Trump retook office, each flight carrying more passengers than the one before. In total, DHS has deported 295 Haitians.

One local Haitian community activist, who spoke to The OBSERVER on the condition of anonymity, said most Haitian immigrants have some type of legal status, whether a work permit or asylum. The activist said some who were on temporary visas have applied for work visas but so far, nobody he knows has been granted a work permit.

He said several have experienced significant declines to their mental health after they had to stop working.

“They need money to pay rent and for food,” he said. “They are suffering.”

He also explained that many were happy in Haiti and had no intention of coming to the United States until they lost loved ones to gang violence, giving them no choice but to leave.

California is home to roughly 218,000 Black immigrants and roughly 15% — more than 30,000 people — are from the Caribbean, a share that includes Haitians. Nearly 1 in 5 Black immigrants in California works in health care, yet 8% lack health insurance, with the rate climbing to 23% among those who are undocumented.

According to a 2023 analysis by the USC Equity Research Institute, California has about 22,200 undocumented Black immigrants and roughly 700 with TPS. The same report found that more than 121,000 Californians in Black families live in “mixed-status” households where at least one member is undocumented.

Sacramento is home to an estimated 10,000 Black immigrants, including Haitians who face uncertain TPS status.

Volma Volcy, chief of staff for the Sacramento Central Labor Council and Haitian immigrant, explained to The OBSERVER the fear that the Haitian community in Sacramento feels at the prospect of being deported to a country that is controlled by armed gangs.

Volma Volcy, 41, migrated from Haiti to the United States at age 13 and later naturalized. Volcy, the Sacramento Central Labor Council’s chief of staff, knows many Haitian immigrants who because their protected status will be terminated come February live in fear to the point that many have changed their daily routines.

“Even if they still go to work, they don’t want to go out and do nothing now. Just groceries, shopping — the necessities,” Volcy said.

The prospect of losing TPS only deepens their anxiety, with immigrants unsure if, come February, they will be considered illegal overnight. “The life they’ve made here is just going to be completely interrupted and now [they might have] to look back to a place they left looking for a better life,” he said. “It is a state of constant stress, a tremendous amount of anxiety that never goes away.”

Volcy added that conditions in Haiti leave little in the way of safe alternatives for people facing deportation. He recalled how violence claimed the life of a cousin who was caught in crossfire while driving home from work. A stray bullet struck him in the neck and he died, despite having no connection to the shootout.

Returning to Haiti would expose people to the same extreme risks that took his cousin’s life. “Now, the level of fear these individuals are dealing with is beyond anything I can comprehend,” he said.

Haiti’s lack of a functioning government, he added, means there is little access to jobs or health care, leaving deportees to fend for themselves in dangerous conditions.

Dr. Ernest Uwazie, a Sacramento State professor and chairman of the board of Africa House Sacramento, said such fears extend well beyond the possibility of deportation. “They shouldn’t be forced to an environment where you’re constantly worried about getting shot walking down the street by some random bullet,” he said. “Or even being killed in your home.”

Uwazie added that the stress carries significant health consequences. Families rely on TPS holders as breadwinners, and the threat of losing that stability spreads anxiety across entire households. Community organizations, he noted, have been disrupted as leaders avoid public organizing out of fear that vulnerable members could be exposed to immigration enforcement.

Garry Pierre-Pierre, founding publisher of the Haitian Times, warned that the stress alone is taking a toll. In an editorial this summer, he wrote that Haitian immigrants “live in a state of permanent anxiety, where the question of tomorrow is never secure.” He emphasized that health consequences of such instability are overlooked in policy debates, even though stress-related conditions like hypertension, depression, and untreated chronic illness are widespread among Haitian TPS holders.

Pierre-Pierre underscored that deportation is not simply relocation — it is forced return to a country without the infrastructure to meet basic health needs. Haiti’s hospitals have been gutted by years of political crisis and gang control, leaving swaths of the country without functioning clinics or emergency services. “Forcing families back is a sentence to untreated illness and avoidable death,” Pierre-Pierre wrote.

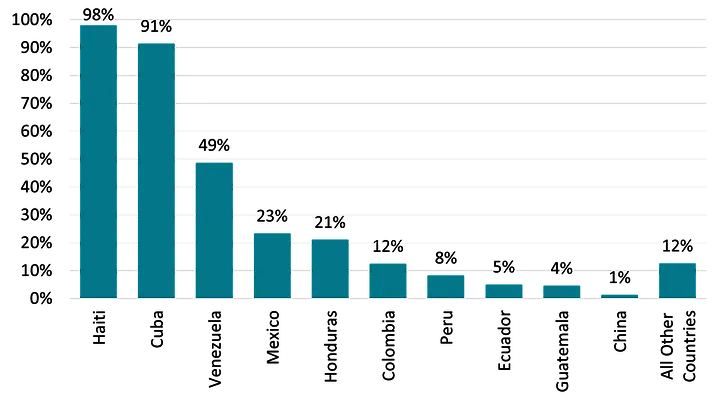

In its July order, the Department of Homeland Security cited a mix of migration pressures, national security concerns, and Haiti’s breakdown in governance as reasons for ending TPS. Officials pointed to a surge in migration: Border Patrol encounters with Haitian nationals rose from 56,596 in fiscal year 2022 to more than 220,000 in 2024. Haitians also have been among the largest groups crossing the Darién Gap, a treacherous jungle route between Colombia and Panama.

Figure 3. Share of Migrant Arrivals at a U.S.-Mexico Border Port of Entry, by Top Nationality, FY 2024

Source: CBP, Nationwide Encounters, updated October 22, 2024.

U.S. officials acknowledged the deteriorating conditions in Haiti. The Congressional Research Service described the country as being in the grip of gang control following the 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse. The State Department recently designated two major Haitian coalitions — Viv Ansanm and Gran Grif — as foreign terrorist organizations, citing their role in fueling violence and instability.

Volcy said these are the very conditions that make deportation so dangerous. Pierre-Pierre described it as a contradiction: the government acknowledges Haiti is overrun by gangs while simultaneously insisting it is safe enough to send people back.

Uwazie warned that deportations would not only destabilize families but also deepen worker shortages in sectors such as health care, while cutting off remittances that Haitian immigrants send home to support relatives abroad. For the communities left behind, he called it “a double whammy.”

Volcy wants lawmakers to recognize the contributions Haitians have made in the United States and to grant them the same courtesy extended to other immigrants. “These are not the criminals that Donald Trump is talking about. Every community they get into, they try to make that community better,” he said. “All of a sudden they cannot work, cannot provide for their families, and have to worry about ICE kicking down their doors, or self-deport to a country they no longer know. That’s cruelty.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is being reported with the support of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.