A hard silence to break: LGBT Vietnamese struggle for understanding

This article was produced as a project for the California Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the Center for Health Journalism at the USC Annenberg School of Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Trauma, cultural barriers make sex education difficult for Asian Americans

Lotus Dao and his parter, Jayelle Greathouse. Photo by Ash Ngu.

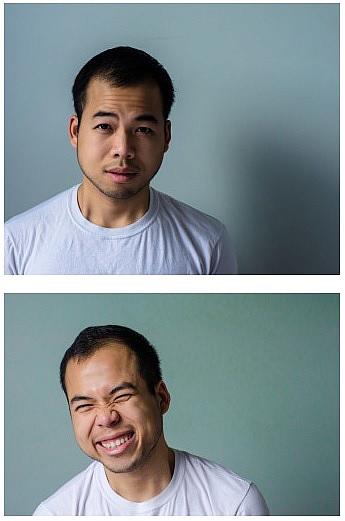

Lotus Dao was seventeen when he came out to his family as lesbian.

It was not planned. He had recently connected with a woman on MySpace, who traveled from Sacramento to visit him in Garden Grove. It was his first time falling in love and his first time meeting another lesbian, and they soon became lovers.

"I became really overwhelmed with feelings. [It was] my first time being physically intimate with another person, and realizing I'm lesbian, and she was really encouraging [me to] just pack up and leave with her," said Dao, who is currently transitioning from female to male.

"My family ended up catching us together, and that's how I came out. It wasn't like a thoughtful plan," Dao said. "I was exploring it privately and I wasn't sure how to come out. And then my mom and my sister caught us together."

That day, the family -- his mother, sister and two older brothers -- gathered in the living room. "I'm a lesbian," Dao said, and his mother began crying. His siblings were silent.

"I think because I came out and it wasn't necessarily a 'that's okay, we still love you,' there wasn't much of a conversation, there was just a lot of crying, so I just internalized it, " Dao said. "It was like, if I can't talk about it, there's no point in me even being here anymore. I'll just leave."

In the years after that incident, Dao felt alienated from his family and left home to study at the University of California, Davis. Lacking support, he began abusing cocaine and alcohol, and struggled with an eating disorder. It wasn't until he was hospitalized for a drug addiction and the hospital called his nearest relative, his brother in Sacramento, that Dao reconnected with his family.

Now a social worker who works with foster youth throughout the Bay Area, Dao has come a long way since that evening seven years ago, which his family has still never discussed.

'A Western Disease'

Dao, who is Vietnamese American, represents a common experience within a community that not only does not discuss sex and gender, but also where family lines of communication have been weakened by war trauma, language barriers, and cultural rifts.

For lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people like Dao, that struggle is all the more complicated.

That was on full display in 2013, when an alliance of gay and lesbian Vietnamese groups applied to participate, as they had been for three years, in the annual Lunar New Year parade in Westminster. Known in Vietnamese at Tết, the holiday celebrates family, ancestry, goodwill and luck for the year ahead.

So many did not expect the controversy that would unfold when the politically influential community group organizing the event, the Vietnamese American Federation of Southern California, refused to accept their application.

The incident sparked a community-wide discussion about equality for LGBT individuals and the parameters of traditional Vietnamese values.

"We were called 'sick,' that this is a 'western disease,' 'your parents didn't teach you right,'" said Hieu Nguyen, recalling what some who did not want the group to participate in the parade had said. Nguyen, who grew up in Orange County, was one of the key organizers behind the parade effort and later formed a non-profit called Viet Rainbow of Orange County.

VROC supporters march during the 2014 Tet Parade. Photo courtesy of VROC.

Although the LGBT groups were barred from participating in the 2013 parade, media coverage from across the country, pressure from parade sponsors and supporters within the community pushed for their inclusion the following year.

Among those who reached out to Viet Rainbow after the media coverage of the Tet parade controversy were parents of LGBT youth, looking to understand what their children are going through.

Viet Rainbow has also since organized a support network for parents of LGBT children -- an informal group of mothers and fathers who meet occasionally and offer their support and advice.

"One youth connected with me [on Facebook] about his parents, and another brought her mother to our group...and both situations turned out to be really positive," Nguyen said. "The gay youth says his mother has been really accepting and that she would like to meet us to say thank you. The other youth said their relationship has improved significantly."

Last year, Viet Rainbow also marched in the San Francisco Pride Parade -- the largest gay pride parade in the nation -- and several mothers came along for support. Amid the crowd, Nguyen spotted Vietnamese people waving to them from the sidewalk, emotional to see children and parents marching alongside each other in the parade.

"That is so desirable, that feeling of belonging...being proud of yourself and seeing the representation of love from parents," Nguyen said. "That's powerful, and profound, and impacted us a lot."

Finding the Words

Nearly every family has struggled at some time or another for understanding: the things you wish you could say; what you hold in your heart out of fear the other won't understand; and that gnawing conflict between protecting your own fragile sense of self and wanting to comfort the other.

In the immigrant family, the gulf of language and culture that separates parents and children can make those feelings all the more intense.

Toan Nguyen, now 24, came out to his mother in high school in Tampa, Florida on the car ride to school. It was a clumsy and awkward conversation, because he didn't know how to describe his sexual orientation other than the word bê đê.

Although bê đê is a common colloquialism to refer to gay men or homosexuality in general, it is often used in a demeaning or derogatory way.

"I felt like I was calling myself a faggot - and it was the first time I was describing myself to my mom," he said. "It was difficult when she started freaking out...saying, 'who taught you to think like this? Who are you hanging out with?' I felt very helpless." Toan Nguyen said.

Hieu Nguyen said he wasn't aware of any terminology when he came out as gay to his family -- and while later supportive, they were initially very upset.

"They themselves didn't have a good knowledge or idea of sexuality and what it means to be gay. All these years, all they've heard is really negative things," Nguyen said of his siblings. "'Thằng đố bê đê,' (meaning 'that man is gay') people laugh, the images they see on TV is like, guys dressing up in women's clothing, that's what they think being gay is."

His mother was initially in denial.

"She said, 'you're not, you watch that MTV show,' she thought I was influenced by American culture, [that] it's a western disease," Hieu Nguyen said.

She also carried many of the misconceptions that Hieu Nguyen heard during the Tet parade controversy and subsequent outreach efforts.

"My mom, her friends asked her this question -- they were wondering if my genitals work. Does it mean that I don't have a penis, or it doesn't work? They thought I can't impregnate someone, that it doesn't get aroused," Hieu Nguyen said. "I think [my mom] might still think that me being gay means I want to be a woman...their understanding is really attached to gender roles."

It's not uncommon to see columns in Vietnamese American newspapers and magazines giving advice about sexual health and pleasure, although those are largely geared toward married, heterosexual adults.

In Asian societies in general, discussing sex and sexual health is taboo, and even words to describe sexual organs or reproductive health are a touchy subject. Colloquialisms or euphemisms, like bê đê, are commonly used, but also carry a stigma.

Late last year, the nonprofit Asian Health Services in Oakland released a 22-page glossary of LGBT terms in Vietnamese, Chinese, Korean and Burmese geared at helping doctors and patients communicate about ideas that have different connotations in each language, according to Oakland North, a news project of UC Berkeley's Graduate School of Journalism.

The glossary is especially aimed at monolingual LGBT individuals who may not be familiar with terminology in their language for words describing sexual organs, STDs, mental illnesses such as anorexia and bulimia, and words like trauma and suicidal tendency.

Hieu Nguyen says since the parade controversy, he and other members of Viet Rainbow have been invited on Vietnamese television shows to talk about their experiences coming out and to explain issues and terminology to Vietnamese-speaking audience.

"We're all about saving face...but there's nothing to be ashamed of. Maybe that's my Americanized ideologies, but from my experience, these kinds of conversations are really important," said Hieu Nguyen.

'Its Just a Phase'

Toan Nguyen, Hieu Nguyen and Dao all said they never discussed sex, gender or relationships with their parents growing up.

Toan Nguyen said after he came out to his parents, his father told him it was just a phase.

"[He said] that I really shouldn't be thinking about these types of things and focus on school work -- don't let these types of things going into my head," Toan Nguyen said.

Dr. Clayton Chau, a psychiatrist and therapist who counsels patients about sex and LGBT issues, says many parents simply avoid the taboo topic of sex at home and are happy to have sex education addressed by their child's school.

"We don't talk about sex - we all know that," said Chau, who is currently the medical director for the Behavioral Health Department of Los Angeles County's healthcare plan, LA Care. "I've encountered elderly Vietnamese couples who reach certain age, and they just automatically sleep in separate beds and rooms. When I tell them there's no reason [to], it's sort of surprising to them."

Many parents urge their children to abstain from sex or wait until after they finish school to get married, and view sex and relationships as a potential distraction or barrier to their child's academic or professional success, Chau said.

In addition to prejudice or shame associated with the belief that homosexuality is a disease, Chau said he has also encountered many Vietnamese parents who associate their child's sexual orientation with the stereotype of gay and lesbian entertainers and hairdressers -- and as a result, fear their children will fall into a lifestyle that will keep them from successful careers.

Even if they do receive that education in public school, many Asian American children report that abstinence and the biology of sex was the main focus of their sex education.

A consequence of that is that Asian Americans are the least likely to use protection, with 40 percent of Asian American women having unprotected sex in their lifetime, according to a 2005 study. Another study found that 44 percent of college-aged Chinese and Filipino women used withdrawal as a contraceptive method, compared to the national average of 12 percent.

Nationally, Asian American women have the second highest percentage of pregnancies that end in abortion, at 35 percent. The country of Vietnam has among the highest rates of abortion in the world, with 40 percent of all pregnancies ending in termination.

Meanwhile, a strong body of academic research has shown that parental communication about sex delays adolescent sexual activity and reduces risky behaviors.

But in Vietnamese families those conversations are few and far between. A2013 UCI Irvine study in the Journal of Minority Health of Asian American college-aged women found that while 54 percent of the Vietnamese women surveyed said their parents talked to them about abstinence, only 12 percent said their parents discussed birth control.

Most Vietnamese immigrant parents living in the U.S. today grew up in homes that did not discuss sex and received little to no education on sexual health and contraception.

That is a silence that gets passed on, Dao said.

Their family transition from Vietnam to Santa Ana was difficult. After Dao's mother left their father, Dao's brothers had to hustle in their early years in the U.S. to help support the family.

"I don't want to blame it on my mom, but I think because she was more focused on making money or paying the bills, to make rent, move into a safer neighborhood, [that she] didn't think it was important," Dao said.

Displays of affection were rare -- they did not hug -- and Dao's mother showed her love through her anxieties, like constant reminders about his health.

It wasn't until Dao began menstruation that his mother made any reference to puberty -- by urging him hurry up and clean up the spot of blood on the sheets, and handing him some tampons.

"I wonder if [that shame] contributes to how much I hate my period -- like it's more than being a transgender man, it's also because we never talked about it," Dao said.

"When I went away from home, I didn't know how to say no, I didn't know what healthy sex was. That contributed to me experiencing sexual violence, and exposing myself to unsafe situations," Dao said. "She didn't know how to talk about it, and I didn't know how to live with it, and it became this really messy situation."

Chau says parents don't realize that avoiding the subject of sex often results in children hiding relationships or other details about their life, building a barrier in their relationship.

"I tell them that...many of you work two jobs and have less quality time, and now you create this barrier and secrecy, and it pushes you apart," Chau said.

Talking about sex or relationships, and how to navigate those realms, also opens up a line of communication for when a difficult situation arises, such as sexual violence, Chau said.

"It applies with any parent, but I think it's much more important for Vietnamese American parents, especially for ones with English proficiency issues," Chau said.

Chau believes that the Vietnamese American community in some ways has been more traditional and conservative about sexuality than the society in Vietnam.

Hieu Nguyen said he was proactive about bringing up and educating his family about LGBT issues, whether his family was watching a movie that included LGBT people, or if his mother was avoiding the subject of his partner.

"When we don't talk about it, it doesn't exist. So for awhile, that was what my mom was doing," said Hieu Nguyen. "I was very conscious in terms of exposing her...I demanded my mom that if she wanted to know what was going on with my life, that she hear everything -- not that she wants me to leave out that I was dating a guy."

Hieu Nguyen believes that strategy -- asking for, often demanding, what he needs -- helped guide his parents toward acceptance.

"You have to help them along - they don't know any better. I do get frustrated, but I know it's my responsibility, because if I don't have open conversation with them, it's not fair to expect anything different."

A Turning Point

In the months after he came out to his family, Dao isolated himself and waited for his high school graduation. He registered for summer classes at the University of California, Berkeley, hoping to move out as soon as possible.

"In a lot of the gay community, there's a lot of drinking and substance abuse and partying, people trying to cope with their feelings. And so I got into that scene," Dao said of his first two years of college.

Cocaine was his drug of choice. Also struggling with an eating disorder, he liked the way the drug made him thin, to appear more masculine. After Dao was sexually assaulted at a party, his substance abuse escalated.

During his second year of college, Dao was hospitalized, and doctors called his closest relative, his older brother in Sacramento, and his sister. They had barely kept in touch over the last few years.

"They saw me struggling. They visited me in the hospital and they also visited me when I went to rehab, and when I was hospitalized again. And they never told my mother," Dao said.

His family never talked about his coming out or the drug use, Dao said. It wasn't until his college graduation ceremony years later, that his mother, crying, acknowledged what had happened.

"She said, 'You've been through so much, I'm so proud of you.' And that's the closest she's ever gotten to referring to anything. And it was amazing to hear," Dao said.

As Dao began to stabilize he began reaching out to his mother, writing her letters to practice Vietnamese and learning about her past. They were among the families that turned to Viet Rainbow to help rebuild their relationship.

They hit turning point last summer, when he, his mother and older sister took a trip to Vietnam.

Dao, who had recently come out as a transgender person to his sister over the phone, planned on telling his mother on their trip. He decided that this time, he would use his mother's communication style.

"I thought about it for a long time, because I felt like we worked so hard to reconnect and have a healthy relationship, and I didn't want to put that at risk, by coming out again," Dao said.

On the trip, Dao shared a hotel room with his mother and left his hormones in the refrigerator where she could see it. Dao let her watch, without explaining, as he used a chest binder to compress his breasts.

"My sister said, 'mom is asking like, what is your sister doing, what's that in the fridge,' and I was just like, 'tell her to talk to me,'" Dao said. "And it was really entertaining, because my mom just did not know how to bring it up."

While in Vietnam, Dao was able to get by as a transgender man until it was time to use a public restroom. If he used the men's bathroom, people might stare or ask him to leave. If he used the women's restroom, they would call security. Binding his chest in hot weather made him light-headed, and he couldn't walk for more than a few hours at a time.

Eventually, she did ask Dao questions, a lot of them. And rather than use the word "transgender," which Dao felt could be alienating, he explained the process of transitioning: that he uses hormones because they make him more emotionally stable and because they change his body, that some day he might get surgery.

"And so I kind of framed it around my happiness, and what feels good for me. At the end, she looked at me and said, 'that makes sense' -- she kind of connected the dots with my growing up, and said, 'I'm not surprised,'" Dao said.

"It was really beautiful because for the rest of the trip she tried to be my ally. I think she started seeing people mistreat me in public...[and] whatever transphobia she might have had, she threw out the window and became the protective mom."

After they returned to the United States, Dao's mother began calling him every few days to talk, sometimes just to hear his voice. Recently, they discussed her moving in with him when she gets older. When Dao brought up his partner, she said they didn't need to talk about it.

"I said, if you want to live with me, we need to talk about it...And she started getting emotional and teary. I was like, do you still have a problem with me being queer?" Dao said.

He was surprised by her reaction.

"She was like, 'no, I don't have a problem with you being lesbian, I don't understand why you have to make your life harder.' And I thought that was really interesting," Dao said. "She said, 'I know lesbians don't get treated well. And we're already immigrants, and we're already not white, I don't understand why you can't do what your brothers do and be straight and get married.'"

"I don't think she's homophobic, her response is out of fear," he added.

When the Asian Health glossary was released, Dao learned a new word,chuyển đổi giới tính, which translates to transgender people. He is still unsure whether he will use that word, given the stigma and how his mother reacted the first time he came out.

"I'm wondering if it will bring peace or understanding. So far I don't feel the need to use that word," he said. "I usually just tell her, I love who I love and sometimes it's a woman and sometimes it's a man, and sometimes they were a man and then they were a woman. And she's like, 'what!'"

Dao is ten months into his hormone replacement therapy and has a surgery scheduled for September to remove his breasts. Now finally beginning to feel happy, stable and comfortable in his own skin, Dao is planning to move in with his partner, and get married and begin fostering children.

Dao's brothers have struggled with accepting his transition. His mother and sister, meanwhile, are among his strongest advocates.

Dao's mother said she is still mourning the loss of a daughter.

"She said, 'I have to figure out what it means to have a son.' I told her, for me, I'll always be her daughter. Even though I'm her son now...it's not like we have to throw that away," Dao said.

[This story was originally published by Voice of OC.]

Photos by Ash Ngu and VROC/Voice of OC.