Health in the Colonias of Texas

Nearly half a million Texans live in substandard conditions in colonias -2,300 unincorporated and isolated border towns with limited access to potable water, sewer systems, electricity, sanitary housing or health care. Hunt Grant recipient Emily Ramshaw reports on health conditions in these overwhelmingly impoverished villages for the Texas Tribune and the New York Times.

Part 1: Improvement Comes Up Short in South Texas Colonias

HARLINGEN — Ask many of the officials charged with improving conditions in Texas’ colonias about their progress and you will receive a string of pre-packaged responses: how generous state and federal budget writers have been, how wisely money has been spent, and how cooperatively they have worked together to aid the more than 2,300 impoverished villages on this side of the Mexican border.

“I don’t want to be bragging, but the fact that we have several state agencies that have programs dedicated to the colonias, I have to give credit to the state for being able to provide some resources,” said David Luna, director of the Texas Health and Human Services Commission’s Office of Border Affairs. “There’s always a need for more. But being in public service, you have to learn the system and be patient.”

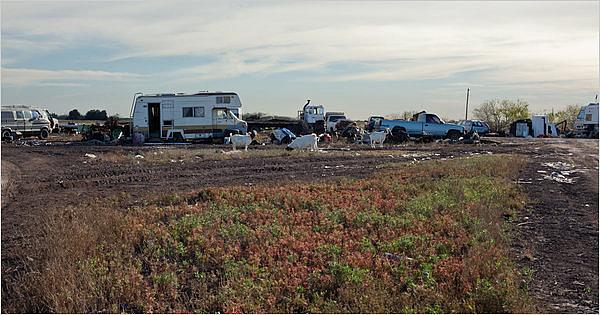

Patience is all the inhabitants of many Texas colonias have had. In Del Mar Heights, on the fringe of Cameron County, residents live on a devastated stretch of scrubland littered with dilapidated trailers and dotted with listing telephone poles.

There are no paved streets or sewers, basic infrastructure that developers promised the Mexican immigrants who bought land here 30 years ago. There are often three families — and several bleating goats — to a lot. Floodwaters and hurricanes routinely sweep through the area, battering roofs patched with tarps and campaign signs.

“The elected officials remain pretty ignorant about all these issues,” said Ann Cass, executive director for Proyecto Azteca, an organization that helps build safe and affordable homes in the Rio Grande Valley’s colonias. “There’s so much turfism, so many bureaucratic challenges. If we as a nonprofit can’t cut through all the red tape, how can we expect one of these families to do it?”

Conditions have clearly improved in the colonias — Spanish for “neighborhood” or “community” — since they were first established in the 1950s. At that time, opportunistic developers took worthless land, created unincorporated subdivisions with little or no infrastructure and began selling lots to predominantly Hispanic migrants looking for cheap land, often locking them into sky-high interest rates and precarious contract-for-deed mortgages. Of the nearly half a million residents in the colonias, an estimated 64 percent were born in the United States; some 85 percent of those under age 18 were born here.

In the last two decades, state and federal officials have invested hundreds of millions of dollars in roads, water lines and other public works projects and have taken legal action against the most unscrupulous developers. In the last four years, at least 250 more colonias got potable water, paved roads and wastewater systems, and 17,000 people moved out of conditions classified as the highest health risk, according to the Texas secretary of state’s most recent report.

But advocates say many of these efforts have fallen short, and that even the best laid plans have had unintended consequences. Bureaucratic nightmares keep basic services and health care out of reach for many, and Catch-22s lead to a spiral of confusion and fees.

Many residents are duped into spending so much of their savings on land that they cannot afford to pay their taxes, let alone build a safe home, said Armando Garza Jr., mayor pro tem of San Juan and an advocate for the colonias.

When they cannot build to code, Mr. Garza continued, they cannot pass inspections to connect to water lines, sewers and electricity, and they are relegated to third-world conditions — dragging extension cords and hoses over from their neighbors, using outhouses in lieu of flushing toilets, and adding on one substandard room at a time in a mess of concrete, tarps and composite wood.

“You need a permit for this, a permit for that,” Mr. Garza said. “It’s so expensive; it’s out of reach to connect to sewer, to water, even when it’s available.”

Nieves, who declined to give his last name because he is in the United States illegally, is trapped in this cycle. He and his wife bought a lot on a rutted caliche road in Mexico Chiquito, outside Pharr, for $9,500 cash several years ago but cannot afford the hook-ups required to start building a home. Instead, they pay $200 a month to live without hot water or electricity in a dirt-floored rental shack next door, sharing a bedroom with their three teenage sons.

“Once our oldest son turns 18, we’ll pass the deed on to him, because he’s a citizen,” said Nieves, a grease-blackened mechanic who came to the United States from Matamoros, Mexico. “We’re here so he can get an education, rise up. God willing, he will build on this land.”

Many programs designed to help families like these have seen little to no growth in financing over the last decade; others have faced cuts. State and federal grants ebb and flow depending on politics and the economy. When they are available, it is often a dog pile, with cities, counties and nonprofits competing for dollars.

“When there’s a dollar on the table, it’s all about who’s going to get it,” said Shirley Arnolde, head of nursing for Proyecto Desarrollo Humano, a community empowerment group.

Many advocates for colonias point to a glaring disconnect between ideas and results, between progress and reality. In interviews with nearly a dozen state, county and federal officials, they spoke of their “coordination” and “oversight,” their “stakeholder” participation. They listed reports they had commissioned and statistics they had collected. And they described public works projects and success stories that seemed, over the course of a week spent in the colonias, to be the exceptions, not the rule.

“In any bureaucracy, there are limitations. We work within those limitations and do the best with the tools we have,” said Enriqueta Caballero, director of the Texas secretary of state’s Colonia Initiatives Program, which she described as “not funding, not regulatory, not enforcement — more of a coordinating agency.”

“It’s not an easy fix,” Ms. Caballero added, “but it’s a great feeling to go out there and see projects and say, ‘Wow, it was done.’ ”

Cameron Park, a colonia on the outskirts of Brownsville, is the best example. Less than a decade ago, it had impassably muddy dirt roads, no city services and few homes up to code. Today, 90 percent of the streets are paved. There are sidewalks, streetlights and bus stops, “all those things normal people are used to,” said Alix Flores, the community development director for the Brownsville Community Health Center.

But Mr. Flores said the changes did not come through sweeping government grants or benevolent agency officials.

Rather, he said, they came through community mobilization. Residents became activists for improving their conditions, registering thousands of people to vote over the course of a few years and holding elected officials accountable for changes.

This is harder than it sounds in communities where residents fear authority and drawing any attention to themselves by registering to vote or demanding services. And the every-other-year election cycle for state lawmakers does not help: advocates for the colonias are constantly forced to educate and re-educate legislators.

“We’ll make progress,” said Oscar Muñoz, deputy director of the Colonias Program at Texas A&M University’s Center for Housing and Urban Development. “But every time we have elections, it’s almost like we have to start all over again.”