Healthy Hillsborough: Keeping kids healthy

This story takes a look at factors at school and in the home that contribute to childhood obesity.

Other stories in this series:

Kenly Elementary School has cut out candy and made the lunch menu even healthier in attempts to combat childhood obesity.

TAMPA - When 11-year-old Shania Lape sees an overweight classmate struggle to keep up, she's filled with sympathy.

"They can't run as fast, they can't play the games at school because they're not healthy," said Shania, a fifth-grader at Kenly Elementary in Tampa.

Worse yet, not being able to play with their classmates could lead to a lifetime on the sidelines for some kids.

The effects of being overweight or obese run the gamut from lower self-esteem to depression and anxiety. Those students also can run into academic difficulties, which can translate to less economic success in adulthood, said Tampa psychologist and USF pediatrics professor Perry Kaly.

And no parent wants that.

"Imagine the pressure: You already know you're overweight, and your teacher, your nurse and your peers are telling you you're fat," Kaly said. "It's unbelievably crushing. … You start thinking you're not loveable or acceptable."

The problem is especially prevalent in Florida, where one in three children is overweight or obese, according to the Trust for America's Health.

As those children grow into teenagers, an otherwise bright future can dim because of their health. Overweight adolescents have a 70 percent chance of becoming overweight or obese adults, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Experts say a combination of factors -- including school lunches, neighborhood norms and cultural traditions -- contribute to the pounds children pack on.

But most agree children's eating habits – good or bad – start at home.

"There needs to be a pervasive thought inside the house that we need to eat healthier, said Denise Edwards, a doctor and director of the Healthy Eating Clinic at the University of South Florida. "There has to be buy-in from the parents."

Parents can influence a vicious cycle that puts their kids at risk without even knowing it.

"Some of it is cultural – they're used to eating certain types of food and are unaware," Edwards said.

Childhood obesity disproportionately affects blacks, Hispanics and Native Americans, according to the CDC. Blacks and Hispanic adolescents (ages 12-19) have an obesity rate of about 22 percent, compared to their white peers, who have an obesity rate of 14 percent.

But, Edwards added, a lot of it is simply leading by example.

A child with an obese parent or parents has a 50 to 75 percent chance of being overweight, too, according to the CDC.

A 2010 University of Minnesota study on the dinnertime habits of families found that overweight parents are less likely to practice positive family meal rituals – such as eating with the television off or not serving soda at mealtime. They also had higher levels of depression and fewer family rules compared to families with parents of a healthy weight.

"If I could fix the world, I'd get everybody to understand you need to say to a child that we're going to have limitations," said longtime educator and Hillsborough County Schools Assistant Superintendent Gwen Luney.

"Getting parents to understand that setting a nutrition line at an early age is extremely important," Luney, a mother of two, said. "Because it's generational."

* * * * *

It's also financial.

Children from low-income and low-education households are three to four times more likely to be overweight or obese than their peers in higher socioeconomic brackets, according to a 2007 study from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

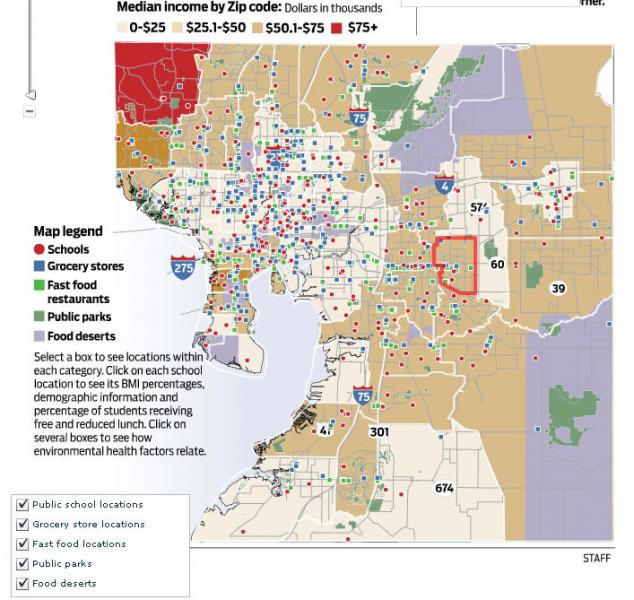

"Neighborhood factors directly and indirectly influence health by shaping health behaviors," said Brian Smedley, director of the Health Policy Institute of the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies.

"It's difficult to sustain healthy behaviors when everything around the neighborhood conspires against good health," Smedley said.

It can start as young as age 7, according to a 2006 University of Michigan study that found people were more likely to be overweight if they thought they lived in an unsafe area. Experts believe many people won't go outside to exercise if they don't feel secure or don't have access to recreational facilities near their homes.

Hillsborough parks manager Peter Fowler said his department works with the school district to ensure facilities are near schools.

"We try to capitalize on the 42 sites where we have after-school and summer recreation programs," Fowler said.

Forty-one percent of Hillsborough County schools are within 1,000 feet of a public park, according to a Tribune analysis. The ratio is likely higher in newer suburban neighborhoods, where development codes require parks or "green space" that can be used for recreation.

It isn't just about urban vs. rural living, though.

Counties are required to measure body mass index (BMI) for first-, third- and sixth-graders in public schools, and Hillsborough data shows schools in low-income areas have higher rates of overweight and obese students.

Tampa's Robles Elementary, where 54 percent of students measured were overweight or obese, is in an area with a median income of just under $19,000. Fifty-six percent of students at Wilson Elementary in Plant City, in a part of town with a median income of $23,780, also measured as overweight or obese.

A majority of students at both schools qualify for free and reduced lunches.

Schools in higher-income neighborhoods tend to have fewer overweight and obese children.

For example, at Grady Elementary in South Tampa, where the median income in the surrounding neighborhood is $54,169 and 49 percent of students qualify for free and reduced lunches, only 16 percent of students are overweight or obese.

* * * * *

Still, Mom and Dad's pantry and piggybank don't necessarily dictate their child's daily diet.

Kids make a lot of their food decisions away from home.

About 55 percent of Hillsborough students eat the basic school lunch, and 35 percent also get breakfast at school. (The county offers free breakfast to all students regardless of income.) About 13 percent of students a day get food from the a la carte line, which offers some healthy choices, but also brownies, soft pretzels and chips.

The days of mystery meat and unidentifiable vegetables ladled onto a green plastic tray during school lunch are over, but there are still problems.

Many parents are unaware of what's offered. "They assume they have more fruit and vegetable options than they do," said Edwards, who packs her three children's lunches four days a week to make sure they get a healthy meal.

With the help of a federal grant, students at some of the poorest schools learn about foods they might not get at home, such as edamame or pomegranates, and get to taste them as a classroom snack.

"It's not just what they're offering, it's the buy-in from the kids," Edwards said. "It's teaching them how food can help them perform, foods that help them grow."

School Nutrition Services Director Mary Kate Harrison admits there's room for improvement, but school officials have to weigh healthy options with what they can afford – while still maintaining a $96-million self-supporting business.

"Kids' eating habits are formed in the first five years of their life – and when they get to school and we're trying to feed them in 20 minutes, it's hard to change that pattern," Harrison said.

Parents, however, can assert more control over their child's food choices at school. The district allows parents to go online and see what their children buy at the cafeteria. Parents also can work with the school to limit what foods their children can purchase.

It's not foolproof. Tory Horwat, whose three children attend Chiles Elementary School in New Tampa, says it drives her crazy when teachers use candy and sweets as a reward for their students.

"It's someone else who's taking out my choice," said Horwat, whose 11-year-old son has Type 1 diabetes. There are better ways to reward them, she said.

Kenly Elementary in East Tampa has learned to do just that. In 2006, the school stopped selling sweets, said Mary Melvin, a guidance counselor and wellness committee chair.

"There wasn't a great big uprising; we reward them with time outside, and we reward them with something other then candy," Melvin said. "The hardest people to convince were the teachers."

Kenly is constantly revamping its cafeteria menu, and the school used just one gallon of cooking oil for the entire 2009-2010 school year. The health of the 94 percent of students who qualify for a free or reduced-cost lunch has improved, Melvin said.

It's also a goal that the students understand how important exercise is in their lives, Melvin said. And teachers at Kenly are trying to bring more physical activities into the classroom.

Third-grade teacher Chris Abrahamson assigns her students pushups, jumping jacks and rabbit hops regularly throughout the day. During math lessons, for example, the class does a number of exercises corresponding to the answer to an equation.

"It's really important for the kids to get up and move their bodies so that they're mentally prepared for what they're about to do," Abrahamson said.

Currently, elementary schools are required to provide 150 minutes per week of physical education. The unstructured physical activity that many of us know as "recess" doesn't exist in county schools anymore.

A 2009 law mandates that middle-schoolers take at least one semester of physical education, but a proposed bill by Rep. Larry Metz, R-Lake County, and Sen. Paula Dockery, R-Lakeland, would repeal that law. Metz says the move would help the schools save money, according to the Orlando Sentinel. The elementary school guidelines would not be affected.

* * * * *

Of course, all the grownups watching and warnings won't do a bit of good if kids aren't swayed. And it's tough to compete with fast-food restaurants, junk-food makers and video game companies whose marketing is designed to grab children and make them lifelong customers.

Kids as young as 3 can develop preferences for certain brands, such as McDonald's, according to a Stanford University study published in 2007.

In the United States, 67 percent of all households play video games, according to the Entertainment Software Rating Board. A fourth of those users, who play an average of eight hours a week, are younger than 18.

So are we grooming a generation of kids who are doomed to become out-of-shape, unhappy adults, with all the associated health problems?

Maybe. Maybe not.

While obesity rates are still high, there are indications that they're leveling off for now, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

With the right education and choices, health officials hope things can improve.

Healthier food options are easier to spot, from oatmeal at McDonald's to egg-white sandwiches at Dunkin' Donuts. The once purely sedentary pastime of playing video games has evolved into an activity that can require some movement as "exergames" gain popularity.

And experts say the stigma of being overweight hasn't changed much since researchers in the 1960s found that children were biased against their heavier peers.

"Pretty universally they get harassed at school," said child psychologist Kaly. "More and more kids are just overt and unapologetic at kids who are overweight."

He tries to get his young clients to look at themselves in a healthy, balanced way – learning how to enjoy what their bodies can do when they're healthy and fit instead of focusing just on how they look.

And with increased awareness, teachers say, kids are making the connection between their health and their future.

"You could have heart problems, heart attack or something like that," says Kenly fifth-grader Alexis Wheatley. "You should always eat the right foods so when you grow up, you can be fit."

How healthy is your child's environment? A lot depends on your home and school's proximity to parks, grocery stores and fast-food restaurants. Click here for an interactive map that shows information by each ZIP code.