Heroin use explodes in California's Shasta County

In Northern California's Shasta County, a growing number of young adults are consumed by heroin addiction. The problem has quickly grown in the past two years and, some say, is approaching methamphetamine’s popularity. The surge in drug use has fueled a rise in crime levels as well.

This article was produced as a project for The California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowships, a program of the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

To view the video and interactive graphs that accompany this article, click here.

For Ely Erickson, 28, the road to heroin began with a fall into the Sacramento River.

In 2009, he plummeted 100 feet and was flown to a San Francisco hospital. The fall left him disabled with back and neck injuries. He was treated with a prescription for painkillers from a Redding doctor. But when that doctor’s prescriptions were no longer honored in late July 2013, he shopped around on the street. Finding black market painkillers too expensive or unavailable, dealers pointed him to an alternative — heroin.

In matter of months, he was living under the Diestelhorst Bridge, begging at nearby convenience stores. Heroin consumed his life, he said. Six months ago he decided to go clean and entered treatment at Right Road Recovery Program, a drug treatment center in Anderson.

“I would steal for it, I would lie for it,” Erickson said. “Right Road is the only reason I’m not on the streets right now, trying to steal your iPod out of your car and trade it for drugs.”

He is one of many Shasta County young people ensnared by heroin addiction — a problem that has quickly grown in the past two years and, some say, is approaching methamphetamine’s popularity.

A YOUNGER CLIENTELE

Heroin’s use in Shasta County has exploded among young adults, say law enforcement, treatment counselors and health professionals. They point to a path that started with an increase in recent years of young people using and abusing prescription narcotics. But as prices increased for prescription medications sold on the street, younger people turned to heroin, available in Shasta County for about $600 an ounce. The results ripple through the community, with burglaries and thefts on the rise as addicts seek quick ways to get cash to pay for their next fix — before withdrawals punctuated by vomiting, diarrhea, muscle twitches and pain wrack their body within hours of a high.

Hard statistics of just how many Shasta County residents are using heroin are difficult to find in the murky black market, but the numbers of those seeking treatment shine a light on heroin’s growth.

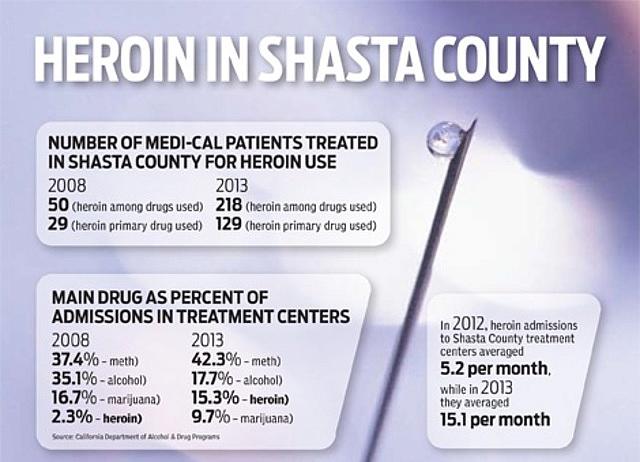

In 2008, 50 Shasta County Medi-Cal patients entered treatment for heroin, with an additional 29 saying it was their main drug. By 2013, those numbers had jumped to 218 and to 181, respectively.

Donnell Ewert, head of Shasta County Health and Human Services Agency, said heroin made up just 2.3 percent of admissions in treatment centers in 2008 — well behind marijuana, which made up 16.7 percent of cases.

By 2013, heroin was the main drug in 15.3 percent of admissions, ranking third behind meth and alcohol.

In the same period, heroin went from causing four visits to Shasta County hospitals for overdoses to 18. Meth overdoses fell from 37 to 21, according to the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development.

The California penal code doesn’t differentiate between heroin and some other drugs, so specific numbers of heroin arrests aren’t available like they are for methamphetamine and marijuana, said Sgt. Les James of the Shasta Interagency Narcotics Task Force.

But heroin has made major inroads into the community, he said, mainly among young people.

Even in Chico, North State heroin is making waves. Chico is home to the only California clinic north of Sacramento that distributes methadone, an opiate used to wean people off heroin or other prescription drugs.

The methadone clinic in Chico, which serves around 395 patients currently, has seen a 20 percent increase year over year.

About 18 percent of its current patients live in a ZIP code in Shasta, Tehama, Siskiyou, Trinity, Modoc or Lassen County, according to Aegis Treatment Center, which runs the clinic.

“We have certainly seen the number of patients in our Chico facility increase significantly over the last 12 months,” said Alex Dodd, president of Aegis.

He said the methadone clinic in Chico has seen an influx of young people. In 2006, 63 percent of methadone admissions were older than 30 in Chico. In 2014, those between 18 and 30 made up 52 percent of the clientele.

Most of the heroin addicts entering Visions of the Cross in Redding are between 18 and 26 years old, said Janet Edmonds, a residential counselor there. Empire Recovery and at Right Road in Anderson also report most heroin addicts are in that age group, their counselors said.

‘HELL ON EARTH’

Professionals trace the root cause of the heroin epidemic to prescription painkillers, such as Vicodin.

Some people began by abusing the drugs recreationally, sometimes as early as when they’re in high school. Others received a prescription that expired and they can’t get refills.

Those using the painkillers recreationally have also been priced out on the streets as prices rise. Recently reformed chemical formulas mean they have to take more prescription pills to get high.

“Nearly half of young people who inject heroin surveyed in three recent studies reported abusing prescription opioids before starting to use heroin,” states the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

In Redding, heroin dealers sell exclusively black tar heroin from Mexico, a much less expensive alternative to black market pharmaceuticals, James said.

“People do sell dime bags now,” he said. How long that lasts for individual users depends on factors such as a person’s weight and tolerance to opiates, though $10 doesn’t buy much. At the height of his using, Erickson would use 3.5 grams — about a tenth of an ounce — throughout the day.

Edmonds said heroin has become so ubiquitous in Redding it can be delivered within 20 minutes of making a phone call.

Many users start off smoking heroin, which removes much of the stigma of the hard drug for younger people, she said.

“If they smoke cigarettes and smoke pot, smoking heroin (doesn’t seem) like a big deal” to them, Edmonds said.

Most of those entering Right Road were smoking it, said Dr. Julian Fuentes, Right Road’s medical director. That reduces the danger of overdose deaths, which public health data show have remained flat. Users seek the high, but as the addiction to opiates develops, they also end up trying to stave off terrible withdrawal symptoms, Fuentes said.

At first, each hit of heroin gives the user a euphoric rush. Eventually the pleasure disappears. For Erickson, heroin’s pleasurable effects lasted about six months before he no longer felt high — instead, he needed it to feel normal.

At that point, to avoid withdrawal, he started to steal. “You’re doing what you need to do to procure the drug,” he said.

Without the drug, he would feel the symptoms of withdrawal — insomnia, cramps, depression, pain in the joints, nausea, vomiting and the “worst case of restless leg,” Erickson said.

“You feel like the whole world is closing in on you,” he said, describing it as “hell on earth.”

Fuentes said heroin users have between four to six hours after taking a hit before withdrawal begins. Withdrawal symptoms can last days.

ADDICTION FUELS CRIME

Heroin users will do whatever it takes to keep from going into withdrawal, said police Sgt. James. That means turning to property crimes, though some keep up appearances of a normal life at first, similar to a so-called “functioning alcoholic,” he said.

“Some go from here to straight down,” he said. “A lot of people kind of slowly, gradually sink.”

Property crimes fell from 2012 to 2013, but rose back to 2012 levels in Redding for the first half of 2014, according to police records. The rise in property crime prompted a community backlash that culminated in a packed town hall hosted by Redding Police Chief Robert Paoletti at Sequoia Middle School in July.

Like methamphetamine users, heroin users turn to property crimes to fuel their addiction. There are, however, differences, Edmonds said.

“Major crimes are the result of meth, these people are ruthless,” she said. “Heroin addicts will steal, but they are more subdued.”

Erickson turned to crime to fuel his habit — in some cases he would fish receipts out of trash cans, steal the most expensive item on the list and return it, pocketing the cash or store credit for drugs, he said.

Breaking into parked cars is also a common tactic, he said.

Those arrested for heroin possession or being under the influence of drugs or alcohol typically don’t stay incarcerated at the jail. When brought into the jail, they are examined by a medical professional, said Lt. Dave Kent.

Medical staff supervise individuals who are impaired or undergoing withdrawal while in custody, he said. They also manage inmates’ withdrawal, with twice daily checks, he said.

“While here, they get proper medical treatment for the state they’re in,” he said.

Narcotics Anonymous and an educational program are also available in the jail to help inmates with addictions. About 27 inmates attend each week, he said.

A VOLATILE COCKTAIL

While heroin’s popularity has grown, other drug problems haven’t necessarily receded, said James, of the Shasta Interagency Narcotics Task Force.

Shasta County is still wrestling with methamphetamine — even in 2013, it remained the No. 1 drug among those admitted to treatment programs. But some are mixing heroin and methamphetamine in a concoction known as a speedball.

Among the 36 total methamphetamine and heroin overdoses in 2013 at Shasta County hospitals, three involved both drugs, according to the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development.

Speedball users may be trying to balance out the effects, but that doesn’t take place, said Fuentes of Right Road.

Fuentes described the forces that may lead to heroin abuse. Drug use in general often pairs with mental illness, he said. Heroin’s pleasurable effects can cover up symptoms of depression, anxiety and other mental illnesses temporarily, he said. As they use, tolerance builds. Eventually they, like other users, begin taking the drugs to feel normal, he said.

Poverty, family history and previous substance use also present major risk factors in drug use, Fuentes said. Middle class users have more money and resources to seek rehab services, he said.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Treatment options vary between outpatient and residential care, but many involve one of two replacements for heroin — suboxone and methadone.

Suboxone is a mixture of buprenorphrine, a mild opioid, and naltrexone, a drug that blocks opiates’ effects. Methadone is another opioid used to supplant the heroin without providing the high.

Dodd, head of the company that runs the Chico methadone clinic, compared it to treating diabetes with insulin.

“What the insulin does is it stabilizes the diabetic, so they can get on with their lives and lead a better life with diet and exercise so one day they no longer have to take the (insulin),” he said. “Addiction is a disease, and it can be treated as a disease. ... What methadone does is it stabilizes the patient, satisfies the brain’s need for opiate painkillers so they don’t suffer withdrawal symptoms. When they’re stable, they can then be responsive to individual counseling and therapy.”

Similar to diabetes, some longtime users may be in methadone treatment for the rest of their life, he said.

Such therapies, however, have many restrictions. Dodd said methadone must be obtained daily by most patients.

Suboxone, a mild narcotic, is also used at Right Road, though its doctor, Fuentes, places tight restrictions on it. He said it allows users to feel as though they’ve gotten their fix, improving their odds in therapy, which teaches them to change their behaviors.

“You’re going to have much higher success,” he said.

They also must be enrolled in counseling and therapy to help change their behaviors and attitudes, he said. Therapy helps address why they started using in the first place.

Erickson said therapy also showed him he wasn’t alone in his heroin addiction.

Only about 10 percent to 20 percent of addicts in general succeed on their first try for recovery, said Susan Wilson, of Right Roads. But the key lies with the addict, who must want to be clean.

For Erickson, the straight and narrow is the clear path.

“When I have urges, I talk with a higher power, I also speak with my sponsor,” he said. “I don’t want to go back to that cycle.”