Importing Doctors: KMC's multimillion dollar deal with Caribbean school marks part of controversial trend

California fellow Kellie Schmitt completed a multi-piece series on the United States' reliance on foreign doctors.

Part One: More than half of Kern physicians were foreign-schooled

Part Two: Are we creating a foreign brain-drain

Part Three: Pace of foreign-physician influx may slow

Part Four: KMC's multimillion dollar deal with Caribbean school marks part of controversial trend

Part Five: Concerns about the quality of Caribbean schools persist

Part Six: Many American students turn to Caribbean medical schools

Caribbean schools are desperate to get their medical students some hands-on training in the United States, evident by their recent million-dollar courting of Kern Medical Center.

On a rainy Wednesday afternoon in April, leaders of Grenada-based St. George's University School of Medicine flew all the way to Bakersfield, check book in hand, to get their students rotations at KMC.

Just a day later, reps from another Caribbean medical school -- Ross University -- came out to make the same pitch and offer even more cash to KMC.

They both brought statistics to disprove the notion that Caribbean students, often Americans who can't get into U.S. medical schools, aren't as good as their stateside counterparts.

Officials were eager to strike a deal with KMC because most Caribbean schools don't have affiliated hospitals that would offer the hands-on training; they only provide the first two years of academic coursework. For their third and fourth years, students must jockey for rotation spots in American teaching hospitals that have Caribbean school contracts.

California traditionally hasn't offered as many opportunities for offshore schools. But the for-profit organizations are trying to change that.

"They've been coming to California with buckets of money," said Dr. Peter Broderick, a Modesto family medicine residency director studying the movement. "The Caribbean school phenomenon is becoming very contemporary for California."

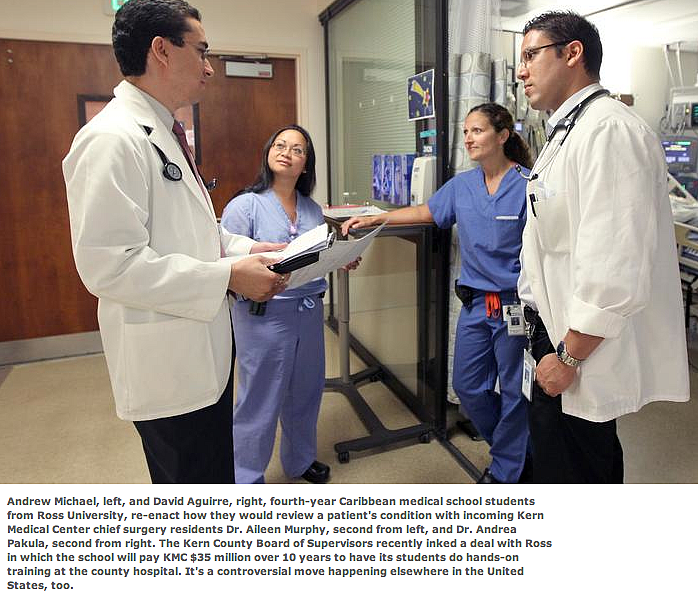

Kern County officials ultimately awarded Dominica-based Ross about 100 slots in exchange for $35 million over 10 years.

The move will feed money into the cash-strapped county facility and could funnel some of those doctors to underserved Kern County. Advocates also point out that Caribbean doctors are more likely to enter primary care specialties, an area of great need for places like the Central Valley.

But the expansion and the money it brings isn't without controversy. Some point to quality concerns since Caribbean schools tend to attract students who couldn't get into U.S. facilities -- an issue that has even risen to the level of a Congress-directed investigation. Others worry that paying for slots one day could squeeze out American-trained students and drive up costs for U.S. schools.

"This is a huge deal," Callie Langton, associate director of health care workforce policy for the California Academy of Family Physicians, said of the KMC-Ross contract. "Kern is one of the biggest hospitals accepting offshore students."

RIPPLE EFFECTS

The Caribbean schools' California expansion comes at a time U.S. medical schools also are trying to grow in anticipation of a doctor shortage. Meanwhile, some experts predict the number of residency training spots will remain constant.

"One can predict as competition goes up, one might see fewer positions offered to international grads," said Stanley Kozakowski, who heads the division of medical education for the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Already, Kozakowski has heard of offshore graduates who can't secure a residency spot, and end up taking jobs as much lesser-paid medical assistants. It's important for U.S facilities to be training medical students who will end up as practicing physicians, he said.

There's also concern that the checkbook-carting Caribbean schools could edge out their non-paying U.S. counterparts, squeezing American students out of rotations. Some predict the U.S. schools eventually will have to pony up cash, too, thereby increasing already high medical school costs.

Over the past several years, medical school advocates in New York have attacked St. George's for its increasing presence in the city's public hospitals.

Several years ago, St. George's inked a 10-year, $100 million contract with New York City's Health and Hospitals Corporation, allowing its third and fourth year students to rotate through those city facilities.

Already, a U.S. medical school received a letter saying one hospital could no longer accommodate its OB-GYN students, said Crystal Mainiero, COO of Associated Medical Schools of New York, a group that represents U.S. medical schools in the area.

"Only a few states take these Caribbean students," Mainiero said. "We had been hoping California would remain strong on that front."

Since offshore schools don't receive the same accreditation as their U.S counterparts, there are concerns about accountability and the quality of the teaching, she added.

"No one is assuring they're holding up any educational standards," she said.

Kozakowski points to his own experience as an education consultant for a hospital in the Midwest. About 125 Caribbean students rotated through the 125-bed hospital in exchange for payments.

When Kozakowski discussed that high ratio with hospital officials, they said they were just trying to pay the bills.

"Is that good for patient care?" he said. "I don't know. It seemed very problematic for me."

KMC's VIEW

In interviews prior to the April meetings, Kern Medical Center leaders expressed some uncertainty about strengthening Caribbean ties. While American schools are a known quantity, the challenge was figuring out which of the international schools offer a top-notch education, CEO Paul Hensler said.

Still, the idea of creating a more formal connection with one school -- and the academic and financial benefits it may bring -- was enticing enough to investigate. The recent meetings with the two Caribbean schools helped alleviate Hensler's quality concerns.

Hensler said Ross' test scores and students are highly competitive; there just aren't enough medical school slots nationwide. Since there likely won't be a Central Valley medical school anytime soon, a close affiliation with a top Caribbean school is a good option for creating a Kern County physician pipeline, he added.

Even though the new deal guarantees Ross students the vast majory of KMC's 100 or so rotations, there will still be room for other schools' students who are connected to Bakersfield, as well as those from UCLA.

A brief email from a senior associate dean at UCLA to The Californian questioned whether the proposal was a good idea, though he said he'd need to consult with other deans before making more comments.

MAKING THE MOST

Broderick, the physician who runs a family medicine residency in Modesto, said he saw the writing on the wall: Caribbean schools are coming to California. In fact, American University of Antigua was interested in paying for slots for his own Modesto program.

And so he began sifting through data and analyzing his colleagues' experiences with Caribbean doctors.

"You have to know what you're dealing with," he said. "It's not all bad."

Paying for slots absolutely could squeeze out U.S. schools, or at least force them to spend money, too, he acknowledged.

As for the quality concerns, finding hard data is challenging since there is no standard repository and all Caribbean facilities don't go through the same accreditation process as American medical schools, he said. Anecdotally, though, Broderick said he's seen both excellent and not-so-excellent Caribbean grads, just like U.S.-trained ones.

One of the key benefits Caribbean schools tout is that they funnel doctors into primary care residencies. Even as a primary care shortage looms nationwide, U.S medical students often choose the higher earning power of other medical specialties, leaving primary care more open for international medical graduates (IMGs).

A Californian analysis found that 42 percent of IMGs from the most common 10 foreign medical schools sending doctors to Kern County were board certified in a primary care specialty such as family medicine, internal medicine and pediatrics. That's compared to just 25 percent of U.S.-trained doctors from the most prevalent 10 American schools funneling physicians to the county.

A large number of Caribbean students are drawn to the primary care specialties such as family practice and internal medicine (though internal medicine residents can sub-specialize later into other fields such as cardiology). In 2012 nearly 26 percent of the first-year residents who graduated from Ross went into family medicine and 43 percent into internal medicine, according to the school.

The more Broderick learned about top Caribbean schools, the more he saw them as a potential solution to California's physician workforce shortage, especially for primary care. The for-profit model, which is independent of the typical financial intertwining of academics and research at major state institutions, works, he said.

Training students for half of their education on U.S. soil also has advantages over bringing in foreign-born, foreign-trained doctors who complete their full studies overseas, he added.

Still, he'd like to see more uniform regulation of the schools' quality, and independent verification of board pass rates. And he stressed the importance of looking at individuals as individuals, evaluating them on GPAs, exam scores and letters of recommendations -- not simply by the school they attended.

Importing Caribbean-trained doctors might have flaws, but Broderick now sees it as at least one way to tackle the region's growing primary care gap.

"It's an interesting solution, and it's definitely got pluses and minuses," he said. "I see the benefits of it and I want us to capitalize on what could be a beneficial solution to workforce issues."