Importing Doctors: From the Philippines to McFarland

Read why the United States imports so many foreign doctors. California fellow Kellie Schmitt completed a multi-piece series on the United States' reliance on foreign-doctors. Physicians from far-flung corners of the globe have ended up practicing medicine in Kern County. These pieces trace the journeys of several international medical graduates -- exploring how doctors from across the world ended up in and around Bakersfield, and what they enjoy about their new lives here.

Part One: More than half of Kern physicians were foreign-schooled

Part Two: Are we creating a foreign brain-drain

Part Three: Pace of foreign-physician influx may slow

Part Four: KMC's multimillion dollar deal with Caribbean school marks part of controversial trend

Part Five: Concerns about the quality of Caribbean schools persist

Part Six: Many American students turn to Caribbean medical schools

Part Seven: Foreign physicians in Kern share their stories - From Burma to Bakersfield

Part Eight: From Sudan to Bakersfield

Part Nine: From the Philippines to McFarland

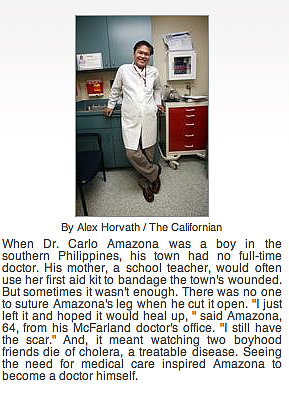

The Philippine farming town where Dr. Carlo Amazona grew up had no full-time doctor. His mother, a school teacher, often bandaged the town's wounded with her first aid kit.

But sometimes it wasn't enough. There was no one to suture Amazona's leg when he cut it open.

"I just left it and hoped it would heal up," said Amazona, 64, from his McFarland office. "I still have the scar."

What left an even stronger mark was watching two boyhood friends die of cholera, a treatable disease. Seeing the importance of medical care inspired Amazona to become a doctor himself.

"I was very idealistic," he said.

Amazona attended Manila's Far Eastern University, Dr. Nicanor Reyes Medical Foundation, a school that has 16 of its doctors practicing in Kern County, according to a Medical Board of California database.

There are lots of doctors in the Philippines, but most want to go abroad in search of higher salaries and better opportunities, he said. Since schools use American medical textbooks and English, the U.S. is a likely choice.

For Amazona, getting to the United States wasn't his original intent; he fell in love with a Philippine nursing student entitled to American citizenship. After working in a Manila clinic for several years, he followed her to California.

There, he worked as an orderly and did health exams for an insurance company as he prepared for the daunting process of becoming a U.S. physician.

"It was terrible, a real struggle, especially since we already had a baby at that time," he said. "But there was no turning back; my wife wouldn't return to the Philippines."

In the United States, Amazona's medical career was shaped by the challenges his foreign training presented.

He took the advice of friends and applied for a residency slot in Detroit, a market more open to foreign-trained doctors than the highly selective California programs. Even though he would have preferred to specialize in surgery, he opted for family practice, a discipline that isn't as competitive and thus more open to foreign medical graduates, he said.

Training all over again wasn't a worthless process; Amazona learned the workings of a developed world hospital system.

"I came from a third world city," he said. "I was amazed -- the hospital where I did my training used all disposable needles."

When it came time for a job, Amazona sought any position in California, near his wife's family. At one point, the best prospect seemed Lerdo Jail.

"They invited me for an interview, and I was scared," he said, laughing. "It was my first time in a prison."

A few days after he declined that position, he fielded offers from Kaiser Permanente in the Bay Area and Clinica Sierra Vista in Kern County. The decision came down to finances. Clinica would pay moving expenses.

The only thing Amazona knew about Kern County was what he had read about in medical textbooks: Valley Fever.

During the past two decades, Amazona has enjoyed his life in Kern County. The weather and sunshine reminds him of his hot island home. His wife likes shopping in Delano's Philippine markets.

In some ways he's come full circle: from a small town in the Philippines without a full-time doctor to serving the primary care needs of a mostly Latino population in rural McFarland, where it's also hard to recruit doctors.

"The patients in McFarland are nice people," he said. "I love my job."

This article was originally published by The Bakersfield Californian.