Inside the newsroom: Ignore radon testing at your own peril

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Sara Israelsen-Hartley, a participant in the 2019 National Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

How looking at an invisible gas could bring change into your home

Kristin Murphy, Deseret News

By Doug Wilks, Editor

SALT LAKE CITY — It’s a colorless, odorless, tasteless gas. It seeps into your home, sometimes getting trapped in basements. You don’t know that it’s there. But it can hurt you.

I’m not talking about carbon monoxide. You’ve heard of that, and the above description applies to carbon monoxide from faulty furnaces and its poisoning effects that can be immediately deadly. It’s why carbon monoxide detectors are as important as smoke detectors in our homes.

But today the topic is radon — colorless, odorless and tasteless — with one other important property: it’s radioactive. Radon is the subject of a monthslong investigation by Deseret News reporter Sara Israelsen-Hartley, a project born from her experience and her persistence convincing her editors that this story had to be done.

Don’t turn away. We understand that this story is not necessarily entertaining. It has nothing to do with the Super Bowl, impeachment, Utah’s failed tax changes, Lori Loughlin, or BYU vs. Utah sports. But a few minutes with Sara’s stories will help you understand this gas, its potential to give you cancer, and help motivate you to take the simple and not-very-expensive steps to get it out of your life.

To be blunt, Sara had to convince her editors (including me) that this was a project worth pursuing. She applied for and received a grant from the University of Southern California Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship. After months of work and the delivery of the story online, and today and Monday in print, here’s what Sara had to say about the project:

Question: How did you first become aware of radon as a problem?

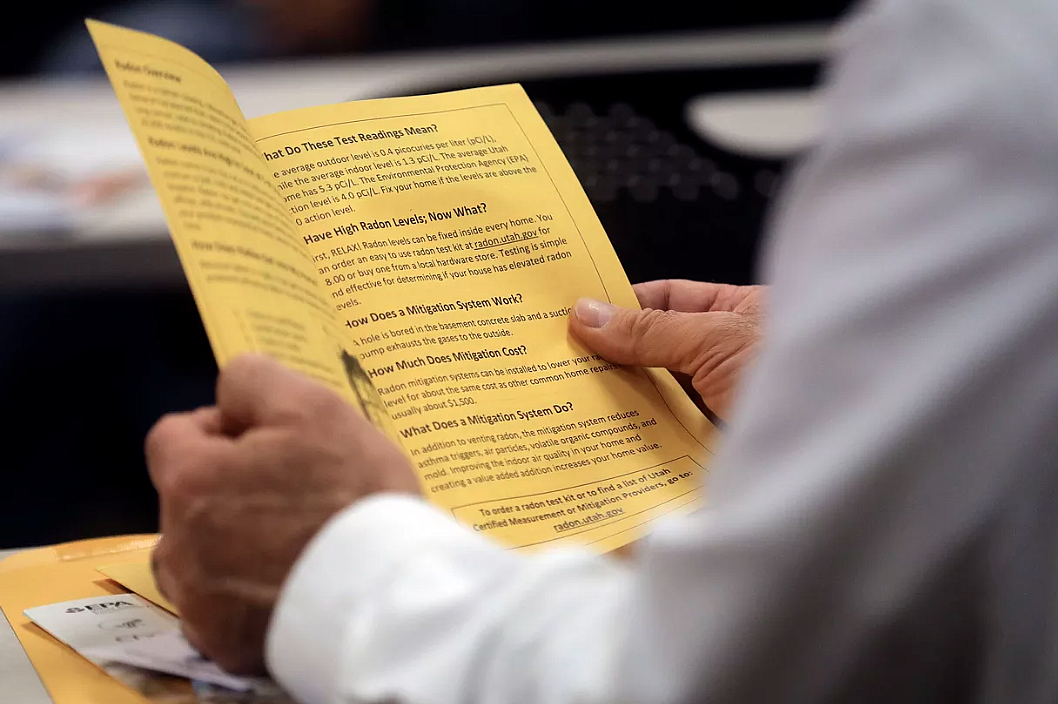

Sara: I think I first became really aware of radon about five years ago, right after my son David was born. Among all the papers I got from LDS Hospital was a brightly colored flyer from the Utah Department of Environmental Quality offering a free radon test kit to new mothers.

Though I meant to order one, in the bustle of a new baby I forgot about it. A year and a half later and after talking with fellow reporter Lois Collins about story ideas, the idea of radon came up. I remembered that flyer and finally ordered a kit, tested my home and found our levels were at 3.6. (Because there is “no known safe level of exposure to radon,” the EPA recommends that families consider fixing their homes if levels are between 2 and 4).

We immediately got a mitigation system and I felt relieved. But the more Lois and I talked, and the more I thought about it, I realized that radon wasn’t something people really knew about or thought about. And there was definitely no sense of urgency. As I really started diving in and asking experts about it, my concerns just grew — especially when I learned that Utah has the lowest smoking rate in the nation, but our biggest cause of cancer death is lung cancer. Radon is a known carcinogen that causes lung cancer.

Question: Should we be worried about radon, given there are so many other things to worry about?

Sara: As a mother, there is no shortage of things for me to worry about. I worry about my kids at school — are they making friends, learning the material, struggling with assignments, eating a healthy lunch? I worry about their future, both in terms of economic opportunities, as well as social connections and spiritual stability. Will they stay away from drugs? Will they see how dangerous vaping is? Will they be able to dodge pornography and sexting and cyberbullying? And those are just the local worries. There’s climate change, political unrest, viruses and health scares, as well as overarching anxiety, mental health challenges and suicide. So why add radon to this list?

It’s true, there are no shortage of things to fear — many of which I have no control over. However, there are things I can control or at least impact.

I can pray with my children daily, I can feed them healthy food at school and teach them about their bodies and why vaping and drugs are bad. I can model mindfulness and proper perspective and bathe them in sanitizer when they come home from school. And I can do something about radon — I can test my home, which we’ve done, and I can add a fan, which we’ve done. Given how prevalent cancer is in our society, it’s very possible they might get cancer someday. However, if I can eliminate one major risk factor now, I will do it.

Question: What did you learn that surprised you?

Sara: I think one of the most intriguing parts of this project was people’s reactions. Some people I talked with were unaware of radon, but eager to learn more, while others were unaware but skeptical about radon being a real problem, even accusing me of “creating” the news. Other people were quite nervous about it, so I reassured them that while radon and radiation is a serious problem, there are things they could do now to reduce their risk.

Another surprising part was just how unregulated this carcinogen is around the entire country. There are no federal laws regarding radon testing, although there are several states that have required testing in public places like schools and daycares, as well as requiring testing as part of real-estate transactions. However, there are a significant number of states, including Utah, where there’s either nothing, or very paltry efforts, to educate people about something that can seriously hurt them, and protect them from it legislatively. In today’s law-soaked society, it just seems odd that we haven’t done more to regulate this known carcinogen.

Final question: What’s the best advice you can give to the public to eliminate radon as a concern?

Sara: Utah is a family focused state, and the majority of our decisions are made to benefit our individual families. Testing our home for radon would fall into that category. However, choosing to tackle radon also provides community-level benefits, because as we make our individual homes safer and talk about radon with others, the entire community becomes safer.

As we are proactive about testing and mitigating, we create a social norm and expectation that radon tests are done when you buy or sell a home. People understand why radon exposure is dangerous and radon mitigation systems become a common sight on homes. We expect that our children’s schools and child care centers will have been tested and we support policies that make testing and mitigation easier and more accessible for everyone.

Doug Wilks is editor of the Deseret News.

[This article was originally published by the Deseret News.]