Left behind: Why Santa Maria became the epicenter for COVID-19 in Santa Barbara County

This is the first of four stories in the weeklong series "COVID Hot Spot: an at-risk city" produced by Laura Place for the Center for Health Journalism's 2021 California Fellowship.

Her other stories:

Part 2: Lost in translation: Language gaps hinder critical COVID-19 outreach in Santa Maria

Part 4: Learning lessons: Community seeks path to health equity as COVID retains grip on Santa Maria

Cristal Robles, who is fluent in Mixteco, English and Spanish, worked as a contact tracer for community COVID-19 cases.

Len Wood, Contributor

Cristal Robles Flores remembers checking the contact tracing spreadsheet in her apartment on a summer day in 2020, noting that the majority of Santa Barbara County COVID-19 cases on her list that day were Mixteco speakers and farmworkers in Santa Maria.

She wondered how many she would be able to reach about their recent contact with someone who had tested positive, and how many would agree to quarantine.

"Being in Santa Maria, and most of [my cases] being agricultural workers who spoke Mixteco, most of the information was out there, but a lot of them weren't aware of what COVID was, what they needed to do to stay safe," said Flores, a paraeducator with Family Service Agency and part-time county contact tracer. "I had a lot of interactions with the population who had a lot of challenges reaching out for assistance because of the language barrier."

At the same time that Flores was handling increasingly larger caseloads, both city and county officials were grappling with how to provide vital information to the same residents, a demographic they had historically struggled to reach.

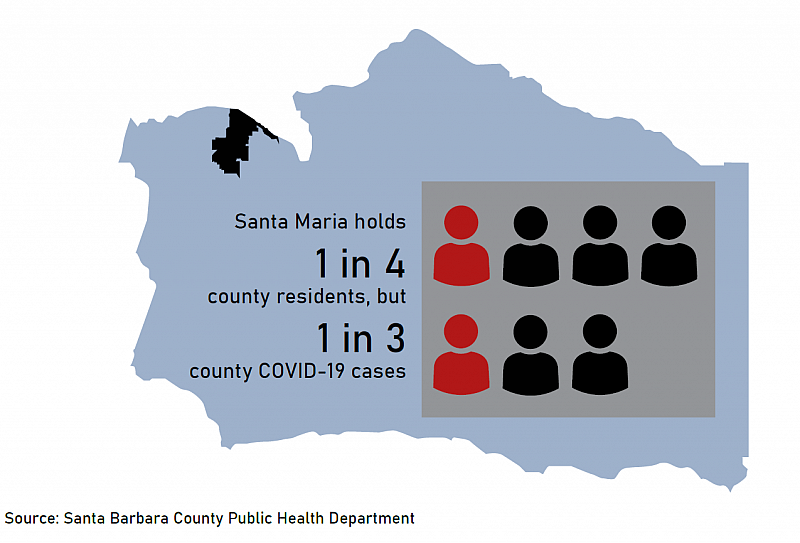

Santa Maria, located at the northern edge of Santa Barbara County, is known for its booming agricultural sector, variety of parks and has a population that is 76% Hispanic. Over the course of the pandemic, the city also became known as a COVID-19 hotspot, accounting for 32% of the county's cases and 35% of the deaths while only comprising 24% of the population.

City Councilwoman Gloria Soto, who has often been the de facto point of contact for the city's Spanish-speaking residents and the wider Hispanic and immigrant communities during the pandemic, argues that initial delays in outreach about the seriousness of COVID-19, accompanied by a lack of financial safety nets such as sick pay and stimulus funds, caused a large portion of that community to be left behind in the COVID-19 fight.

“The folks who needed the information and were most affected, the information was not trickling down to them, and by the time it did, there was nothing they could do,” Soto said.

'The pandemic has only heightened what we already knew'

Santa Maria's population has been disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, holding approximately one quarter of the Santa Barbara County population but one-third of the county's COVID-19 cases and deaths, according to data from the Santa Barbara County Public Health Department. Graphic by Caroline Ambrose

“When I talked to the team and found out the race and ethnicity and occupation of the individuals, it didn't really surprise me or surprise the team, because the pandemic has only heightened what we already knew,” Do-Reynoso said.

According to the California Healthy Places Index (HPI), which examines how community health is influenced by housing, education, transportation and economic conditions, over one-third of Santa Maria residents ages 18 to 64 do not have health insurance, putting the city in the lowest quartile.

The city is also in the lowest health quartile for prevalence of certain kinds of illness: Around 6% of residents live with heart disease, and 10% live with asthma, making it the city with the highest rates of those two health conditions in the county, according to the HPI.

Disparities in the city can also be partially explained by the widespread health inequities experienced by Hispanic and Latino residents in the United States. According to 2017 census data, 16% of Hispanics were uninsured, compared with around 6% of non-Hispanic Whites, and have greater levels of chronic illnesses than Whites.

Ana Huynh, director of Mixteco Indigena Community Organizing Project’s Santa Maria office, said limited access to health care was also compounded by a distrust of traditional medical providers in the city, particularly among Indigenous residents, making the group particularly vulnerable to COVID-19.

“When I talked to the team and found out the race and ethnicity and occupation of the individuals, it didn't really surprise me or surprise the team, because the pandemic has only heightened what we already knew."

— Van Do-Reynoso, Santa Barbara County Public Health director

Around 25,000 Indigenous migrants from the Mexican regions of Oaxaca, Guerrero, Michoacán, and Puebla live in Santa Barbara County, according to MICOP's website, and the majority are believed to reside in Santa Maria.

"The lack of access to health care was definitely a big concern, because historically, the Indigenous-speaking communities in Santa Maria have always struggled with language access at medical offices, doctors' offices, and hospitals. All of us advocates have always tried to … bring it to light to anyone and everyone who would listen, especially the leaders in the community who could have the power to provide this access," Huynh said.

In county COVID-19 demographic data, Indigenous Mexican background is not separated from Hispanic/Latino ethnicity. As of June 30, Latino and Hispanic residents, which comprise 48% of the county population, have made up 59% of cases, 67% of hospitalizations and 50% of deaths.

'Families didn't know what was going on'

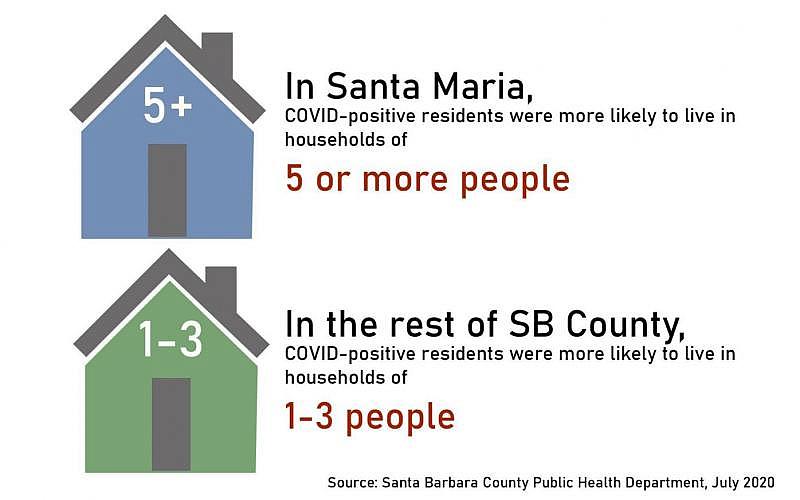

Graphic by Caroline Ambrose

Flores was one of 30 employees from Family Service Agency contracted by Santa Barbara County Public Health to contribute to contact tracing efforts. In addition to their existing FSA roles, such individuals conducted over 2,000 hours assisting the county.

Flores saw firsthand through her communication with those she was able to reach how the crowded living conditions and already-precarious financial situations made following social distancing and quarantining properly nearly impossible.

"Most of the time for the Mixteco-speaking population, when we would ask them to quarantine, they would say 'I live in a home with my kids so I can’t quarantine,' and the next thing you know their wife and kids test positive," she said. “It was very emotionally hard, hearing what the families were going through, and it was emotionally draining, because families didn’t know what was going on and were asking, ‘Should I be super scared?’"

Steven DeLira, FSA executive director, said that local eviction protections passed in the state often didn’t help residents who had multiple families living in one home, as was often the case in Santa Maria. This also made contact tracing difficult, he said.

“A real fear was people who were COVID-positive being kicked out, so they didn’t want the contact tracers to call other people in the house to tell them they had been exposed,” he said. “There was a stigma associated with a positive test, because I don’t think the community knew what that meant.”

Housing is one of the health conditions in which the city of Santa Maria ranks lowest, specifically when it comes to the number of residents per room. According to the HPI, Santa Maria has a higher number of residents per room in a residence than around 97% of the cities in California.

COVID-19 case data from July 2020 confirmed that more Santa Maria residents were living in higher-occupancy households than other county areas — 27% of Santa Maria cases confirmed by then were among residents who lived in households of five people, compared to 15% of cases in other parts of the county.

Further, 16% of Santa Marians with confirmed COVID-19 cases lived in homes with six residents, double that of other county areas, and 8% lived in seven-person households, compared to 2% of cases in other areas. Santa Maria was also the only region at that time with COVID-positive residents living in 11-person households, although that scenario made up just 2% of confirmed cases.

'Now we can go back to the way things were. No, we can't'

Francisca Camarillo, a staff member in the Santa Maria office of Mixteco Indigena Community Organizing Project (MICOP), speaks with a client about the impacts of COVID-19 and possible assistance options in February. MICOP is one of many organizations in the county working to expand access to COVID-19 vaccines in Santa Barbara County. Laura Place, Staff

The formation of the multi-agency Latinx & Indigenous Migrant COVID-19 Response Task Force, which met twice a month starting in May 2020 and continued for 14 months, created a network of resources and outreach that did not exist before.

Huynh said prior to the pandemic, there was little incentive for larger entities like the county or hospitals to offer equal access to medical services and information to Mixteco-speaking residents in particular. However, the pandemic shifted the focus.

"More people in the community, more advocates, more activists, more people fighting for social justice came together and became one big voice countywide. To me, it feels like before the pandemic we didn't have that, in Santa Maria particularly," Huynh said.

As cars line up on the Santa Maria campus, Hancock College staff and volunteers hand off hundreds of food bags during a drive-through distribution on March 31, 2020. Len Wood, Staff file

As of late August, 47.4% of the North County population was fully vaccinated against COVID-19, compared to 62.6% in the South County, according to state health equity data.

In Santa Maria and Orcutt’s four main ZIP codes, the vaccination rate among the eligible population of residents 12 and older ranged from 55% to 65% — in the South County, it ranged from 72% to 84%.

While advocates have noted improvements in outreach, especially in terms of successful collaborations between the Public Health Department and local organizations, much work remains to be done when it comes to maintaining equitable access to medical resources and building trust with the community.

“The hope now is that with these lessons learned, we can only improve and grow from that, versus going back to what was and saying, ‘We’re done, we’ve survived this big ordeal, now we can go back to the way things were.' No, we can’t,” Huynh said.

Editor's note

This is the first of four stories in the weeklong series "COVID Hot Spot: an at-risk city" produced in partnership with the Center for Health Journalism, investigating the risk factors and decisions that allowed COVID-19 to spread disproportionately throughout Santa Maria over the past year and a half. By highlighting the failures and successes in addressing this health crisis and its impacts on the community, we hope to draw readers into growing discussions around health inequity in Santa Maria.

[This article was originally published by the Santa Maria Times.]